|

|

Ibero-American

Journal of Psychology and Public Policy |

Research

Article |

Perception of urban psychological well-being: psychometric properties of a measurement instrument

(Percepción de bienestar psicológico urbano: propiedades psicométricas de un instrumento de medición)

![]() Ricardo

Jorquera Gutiérrez 1,* and

Ricardo

Jorquera Gutiérrez 1,* and ![]() Juan

Rubio-González 2

Juan

Rubio-González 2

1 Universidad de Atacama, Chile; ricardo.jorquera@uda.cl

2 Universidad de Atacama, Chile; juan.rubio@uda.cl

* Correspondence: ricardo.jorquera@uda.cl

|

Reference: Jorquera, R., & Rubio-González, J. (2024). Perception of urban psychological well-being: Psychometric properties of a measurement instrument (Percepción de bienestar psicológico urbano: Propiedades psicométricas de un instrumento de medición). Ibero-American Journal of Psychology and Public Policy, 1(1), 33-56. https://doi.org/10.56754/2810-6598.2024.0006 Editor: Mauricio González Arias Reception date: 14 Aug 2023 Acceptance date: 27 Nov 2023 Publication date: 22 Jan 2024 Language: English and Spanish Translation: Helen Lowry Publisher’s Note: IJP&PP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Copyright: © 2024 by the authors. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY NC SA) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/). |

Abstract: Considering a multidimensional model of psychological well-being as a reference, this study sought to design and analyze the psychometric properties of an instrument to measure the perception of urban psychological well-being. This construct is understood from an ecological-environmental perspective, positioning the individual in relation to the city they inhabit, from which various subjective orientations would be derived. The study was conducted with a non-probability sample of 376 Copiapó, Chile adult inhabitants. Through a Confirmatory Factor Analysis, an adequate goodness of fit of the hypothetical model was confirmed. The instrument's reliability is adequate. The results allow us to conclude that the interpretations made with the instrument have evidence of validity and reliability to measure the construct. Keywords: urban environment; environmental psychology; subjective orientations; reliability; validity; factor structure. Resumen: Considerando como referencia un modelo multidimensional del bienestar psicológico, este estudio buscó diseñar y analizar las propiedades psicométricas de un instrumento para medir la Percepción de Bienestar Psicológico Urbano. Este constructo se comprende dentro de una perspectiva ecológico-ambiental, situando al individuo en relación con la ciudad que habita, de la cual se derivarían diversas orientaciones subjetivas. El estudio se realizó en una muestra no probabilística de 376 habitantes adultos de la ciudad de Copiapó, Chile. A través de un Análisis Factorial Confirmatorio se constató una adecuada bondad de ajuste del modelo hipotético. La confiabilidad del instrumento resulta adecuada. Los resultados permiten concluir que las interpretaciones que se hagan con el instrumento cuentan con evidencias de validez y confiabilidad para medir el constructo. Palabras clave: ambiente urbano; psicología ambiental; orientaciones subjetivas; confiabilidad; validez; estructura factorial. Resumo: Tendo como referência um modelo multidimensional de bem-estar psicológico, este estudo procurou desenhar e analisar as propriedades psicométricas de um instrumento para medir a Percepção de Bem-estar Psicológico Urbano. Este construto é compreendido dentro de uma perspectiva ecológico-ambiental, situando o indivíduo em relação à cidade que habita, da qual derivariam diversas orientações subjetivas. O estudo foi realizado numa amostra não probabilística de 376 habitantes adultos da cidade de Copiapó, Chile. Através de uma Análise Fatorial Confirmatória, foi confirmado um ajuste adequado do modelo hipotético. A fiabilidade do instrumento é adequada. Os resultados permitem concluir que as interpretações feitas com o instrumento apresentam evidências de validade e confiabilidade para mensurar o construto. Palavras-chave: ambiente urbano; psicologia ambiental; orientações subjetivas; confiabilidade; validade; estrutura fatorial.

|

1. Introduction

The study of people’s well-being has recently emerged as a topic of great interest. The intentions are varied, as are the perspectives and disciplines from which approaches have been made to measure a central aspect of the quality of life of a territory’s inhabitants. The first known works were related to the concept of quality of life, where disciplines like economics showed particular interest (Casas, 2010). However, this has been changing, and well-being is beginning to be associated with psychosocial indicators such as interpersonal relationships (Diener & Seligman, 2004), people’s predisposition to social problems, and the spaces they inhabit because, according to empirical evidence, the geographic, social, or cultural contexts in which the subjects live and participate are changing and influencing their perceptions and actions (Berry et al., 1992; Díaz, 2002).

More specifically, environmental psychology has studied the relationship between architectural spaces and the perception of well-being among city dwellers. Hidalgo (2015) notes that various empirical studies confirm that some physical and psychological disorders are related to urban inhabitants’ lack of contact with nature, in response to which it has been proposed that the designs and characteristics of cities be modified consistent with creating more sustainable and healthier environments and thus transform current lifestyles marked by work and information overload, sedentary lifestyles, and lack of contact with nature. Such factors ultimately lead to the emergence of physical symptoms like high blood pressure, hormonal and gastric disorders, allergies, and obesity (Daponte et al., 2015), as well as psychological signs and symptoms such as depersonalization, anxiety, stress, loss of attention span, concentration, and memory (Hidalgo, 2015).

In this context, the notion of the built environment (BE) refers to the setting in which people live (Daponte et al., 2015; Villanueva et al., 2012), the attributes of which would predominantly determine their objective health and perceived well-being (Rahman et al., 2011). In particular, the characteristics and urban configuration of the BE are directly related to childhood obesity (Kleinman, 2009; Villanueva et al., 2012) and various public health issues that affect urban dwellers nowadays. In this vein, the configuration of inhospitable and inefficient urban spaces runs counter to the development of prosocial and friendly behaviors in cities (Gracida-Jiménez, 2015), which leads to urban dwellers’ feelings of distress and alienation for the want of prosocial interaction.

For the World Health Organization (2003), well-being is a fundamental component of human health, both physical and mental (Montoya & Landero, 2008). Given this, the population's concern about this issue is evident; however, it is a complex construct to address since well-being can be understood as ranging from the satisfaction of basic subsistence requirements to needs and aspirations for personal self-fulfillment (Iñiguez & Olivera, 1994). Hence, capturing people's perceptions of their psychological well-being as an indicator of quality of life appears to be fundamental.

Similarly, in its analysis of the perception of well-being, psychology has moved between two traditions: on the one hand, the hedonic tradition of well-being represented by the construct of subjective well-being, associated with the concept of happiness, and, on the other, the eudaimonic tradition represented by psychological well-being and related to the developmental potential of individuals (Ryan & Deci, 2001). Synthetically, the hedonic tradition is logically positioned within the framework of so-called positive psychology; therefore, this approach concentrates specifically on the study of affection and satisfaction with life (Cabañero et al., 2004) and how this relates to human well-being. In contrast, the eudaimonic tradition has its origins in humanist psychology, which focuses on the development of human abilities and personal growth; hence, it is linked to concepts such as self-realization, full functioning, and maturity (Maslow, 1968; Rogers, 1961; Allport, 1961).

To find the convergence of these theoretical formulations, psychologist Carol Ryff (1989a, 1989b) endeavors to broaden and integrate them into one construct, with social, subjective, and psychological dimensions adding to human health behaviors in general, promoting people’s positive functioning. Thus, Ryff (1989a, 1989b) defines the concept of psychological well-being as the effort to perfect one’s potential, characterizing it as a construct that represents each individual’s level of psychological development while interacting harmoniously and satisfactorily with their environment and the activities they perform.

Ryff (1989a, 1989b) develops a theoretical proposal that translates into a multidimensional model of psychological well-being, comprised of six factors or dimensions (Ryff & Keyes, 1995; Keyes et al., 2002): (a) Self-acceptance, related to the positive feelings an individual experiences when feeling satisfied with themself; (b) Positive relations with others, linked to the person's prioritization of developing close relationships with others based on values of trust and empathy (Ortiz & Castro, 2009); (c) Autonomy, which implies sustaining one's own individuality in different social contexts, a factor that leads people to establish their own convictions based on self-determination and thus maintain their personal authority and independence (Ryff & Keyes, 1995); (d) Environmental Mastery, related to the feeling of being able to choose and favorably influence the world according to one’s needs and purposes (Díaz et al., 2006); (e) Purpose in life, which entails a cohesion between the efforts and challenges of the individual, where it is important to establish goals to then deliberate on specific objectives that allow to give meaning to life (Díaz et al., 2006); and (f) Personal growth, related to bringing one’s own potential to a higher state (Ortiz & Castro, 2009). It, therefore, implies a dynamic learning activity in which potential is realized, enabling a lasting development of applied and learned strengths (Keyes et al., 2002).

From the proposal of the six theoretical dimensions by Carol Ryff, the Scales of Psychological Well-being (SPWB) were developed, the high point of which, according to Van Dierendonck (2004), is the procedure used in its construct. At the beginning of this process, three researchers participated and proposed 80 items for each dimension, of which 32 were selected, which were ultimately reduced to 20 items per dimension after a pilot study with 321 adults (Ryff, 1989b). Subsequently, Ryff et al. (1994) developed a proposal with 14 items per dimension. Then, Ryff and Keyes (1995) proposed a version of 3 items per dimension, selecting those that best fit the theoretical model of the six factors according to the psychometric study. Finally, Keyes et al. (2002) developed a version of nine items per dimension.

In general, the factor structures of the SPWB, based on Ryff’s proposal (1989a, 1989b), have been verified by confirmatory factor analyses (CFA), with the debate focusing on the quality of the models from the number of dimensions or factors analyzed (Véliz, 2012). This is how, with a Dutch population study, Van Dierendonck (2004) considers the six-factor model more appropriate, with which Abbott et al. (2006) tend to agree in a study with women in the UK. In contrast, in a study with an American population, Springer and Hauser (2006) conclude that the six-factor model shows deficiencies while presenting high intercorrelations among factors.

SPWB has also been studied in the Spanish population. For example, research by Triadó (2003) and Navarro et al. (2007) on well-being in aging finds acceptable reliability indices in the scales, although the questionnaires are criticized for being too long when using the version with 14 items per factor. However, it is the work by Díaz et al. (2006) in the Spanish context that has been most recognized because, apart from translating the version by Van Dierendonck (2004), it reduces the number of items per factor generating a proposal of 39 items in total, which facilitates its application, also achieving acceptable criteria of validity and factor reliability, and good levels of fit of the theoretical six-factor model (Díaz et al., 2006).

In the Chilean case, Véliz (2012) uses the version by Díaz et al. (2006) translated into Spanish; it has 39 items and includes the six factors. In a study with 691 university students in Temuco, the scale presented acceptable reliability, with the dimension Self-acceptance being the highest (.79) and Purpose in life the lowest (.54). The confirmatory factor analysis yielded an acceptable RMSEA of .068, a CFI value of .95, an NNFI value of .94, and an SRMR value of .060. After these results, the author concludes that the model has an adequate fit, permitting its use in the Chilean university population (Véliz, 2012).

From an epistemological perspective, the proposal of the multidimensional model of psychological well-being or integrated model of personal development emphasizes human well-being based on the development of abilities and the fulfillment of goals that allow people to grow (Romero et al., 2007). From that perspective, psychological well-being has focused on indicators of positive functioning and human potential; however, the truth is that the construct appears much more complex, multifaceted, and dynamic, so it must be addressed from other dimensions.

By way of example, in an attempt to agree on the various meanings people give to the quality of life, the World Health Organization states that it is an individual's perception of their place in existence, within the context of culture and the system of values in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, norms, and concerns (The WHOQOL Group, 1995). It, therefore, follows that quality of life is a complex and broad construct, so the well-being associated with it is also a concept that is complex in its configuration because it is related to the states of physical and psycho-health at the levels of autonomy, interpersonal relations, and elements of their environment (Urzúa & Caqueo-Urizar, 2012), among other dimensions that stand out. This is how the proposal in this paper considers the perception of psychological well-being in its connection with urban spaces, understanding that these also change perceptions of human well-being.

In this sense, urban psychological well-being must be understood as focusing on territorial and urban spaces that people inhabit. This is because the conditions in which people live in cities largely determine patterns of territorial and community organization (Cueto et al., 2016) on the one hand. However, these conditions also generate attitudes and interpersonal values that could provoke psychosocial phenomena such as frustration and aggression, ultimately defining people’s perception of their social world, the support they receive, and their quality of life and well-being (Gracia & Herrero, 2006).

As can be seen, people’s well-being is influenced by different variables, highlighting, among others, sociodemographics and the place where they live. Hence, this proposal considers the perceived urban psychological well-being with a contextualized view, i.e., it considers that people position themselves in their contexts – in this case, urban – and from there create a self-perception of well-being, believing that subjective assessment is a relevant predictor when positioning a subject with their resources (Hicks et al., 2001). From this perspective, the proposal seeks to evaluate the subjects' perception, specifically in their interaction with the environment.

In this light, the perception of urban well-being is enhanced from ecological-environmental perspectives; thus, it includes elements of environmental psychology, which emphasizes the psychological processes by which people adapt to the demands of the physical environment (Baldi & García, 2005), and of the ecological-contextual paradigm, the fundamental metaphor of which is the setting that people inhabit, which operates as lived and meaningful behavior for them (Lara & Lara, 2004). In this way, the perception of urban well-being attempts to establish a dialectical relationship between the natural settings that people inhabit and the subjective orientation they make of them.

From this perspective, the Perceived Urban Psychological Well-being Questionnaire (CPBPU in Spanish) aims to place people in interaction with their complex environment, in this case, the urban context. The aim is to provide a concept and a measuring device to promote the understanding of phenomena and the ways of relating and incorporating themselves into the cities that their inhabitants present (Oviedo, 2002). Hence, the epistemological support of the CPBPU starts from the base that people establish an active relationship with their environment, and from there, mental states emerge that configure judgments, perceptions, convictions, and beliefs. As Oviedo points out (2002, p. 27), "the subject in the city constructs symbolic representations, creates mental images, and designs at a psychic level their own perspective of the city, based on their capacity for abstraction and delimitation of relevant and guiding aspects."

2. Objectives

The proposal's relevance lies in the inhabitants of a city configuring urban spaces as internal representations with which they interact symbolically with the environment in which they live. Hence, the CPBPU emerges as a tool to facilitate the formulation of urban public policies and urban and architectural design. In this light, this research aims to design and analyze the psychometric characteristics of an instrument to evaluate the perception of urban psychological well-being in the Chilean population. In specific terms, the following are sought: (a) to construct an instrument that will make it possible to respond to the object of the study indicated; (b) to study the internal consistency of the items and scale of the instrument; (c) to study the factorial validity of the instrument; (d) to explore and describe initial results collected using the proposed instrument.

3. Method

This section describes the methodology used in this study, broken down into five sections: participants, research design, instruments, procedure, and data analysis.

3.1. Participants

Using non-probability purposive sampling, 376 people, all Copiapó, Atacama Region inhabitants, participated voluntarily. According to sex, the sample distribution was 51.1% female and 48.9% male. In terms of age, 27.9% (n = 105) were between 18 and 29, 49.7% (n = 187) were between 30 and 49, and 22.3% (n = 84) were over 50. According to activity, 71.5% (n = 269) were active workers, 11.7% (n = 44) students, 6.1% (n = 23) retired, 3.7% (n = 14) unemployed, 6.1% (n = 23) homemakers, 0.8% (n = 3) other. According to family income level and considering values in Chilean pesos (CLP), 6.9% (n = 26) of participants reported incomes below $218,000, 25.5% (n = 96) reported incomes between $218,000 and $440,000, 41.5% (n = 151) reported incomes between $440,000 and $670,000, 23.7% (n = 89) reported incomes between $670,000 and $1,800,000, 1.3% (n = 5) reported household incomes over $1,800,000, and 1.1% (n = 4) declined to provide this information. According to education level, 10.9% (n = 41) of the participants had completed basic-primary education, 31.1% (n = 117) had completed secondary education, 33.2% (n = 125) had completed technical-vocational education, and 24.5% (n = 92) had completed university education.

3.2. Design

A psychometric or instrumental design was used per Ato et al.'s proposal (2013). The aim was to design and then analyze the psychometric properties of the Perceived Urban Psychological Well-being Questionnaire (CPBPU). Since the data were collected at a single point, it is a cross-sectional study.

3.3. Instruments

A brief sociodemographic questionnaire was administered to characterize the participants, with dichotomous and polytomous variables, in which gender, age, activity, family income, and education level were requested.

The Perceived Urban Psychological Well-being Questionnaire (CPBPU) is based on the multi-factorial proposal of Carol Ryff's six theoretical dimensions (1989a, 1989b) but adapted to urban contexts from an ecological-environmental perspective. In this sense, the CPBPU consists of 14 questions to assess the six dimensions of the proposed construct. The items were constructed using a theory-based procedure, in this case, Carol Ryff's multidimensional proposal, based on which the construct was adjusted according to the conceptual contentions indicated, and the items were subsequently constructed (top-down perspective).

The factors included in the instrument are:

a) Self-acceptance of the context: aimed at establishing people's self-perception of satisfaction with the urban space they inhabit, considering their life experience. The goal is to obtain degrees of identity with the city, stability, and projections in this urban context. This factor is measured based on three items; one example is: "When I look back on the history of my life in Copiapó, I am happy with how things have gone for me.”

b) Prosocial interaction: aimed at establishing people’s self-perception regarding interpersonal relationships of closeness and trust developed in the urban space. One of the three items of this factor is "In this city, I have managed to have close friends with whom to share my worries and joys.”

c) Context-facilitated autonomy: aimed at establishing people’s self-perception regarding the extent to which the urban space they inhabit has enabled them to create and enhance their identity, autonomy, self-confidence, and individuality to the point of expressing opinions and convictions resolutely and autonomously. This dimension is composed of two items; for example: "In the social contexts in which I participate in Copiapó, I can express my opinions freely, even when they are in opposition to the opinions of most people.”

d) Mastery of the urban environment: aimed at establishing people's self-perception about how the urban space they live in has allowed them to develop their lives and projects according to their needs and purposes. "In this city, I have been able to build a home and a lifestyle to my liking” is one of the two items of this sub-scale.

e) Context-facilitated personal growth: aimed at establishing self-perception of how they have learned and developed in their urban space. This dimension is measured by two items such as: "In the time I have lived in Copiapó, I have developed a lot as a person.”

f) Context-facilitated purpose in life: aimed at establishing people's self-perception about how the urban space they inhabit has been able to give meaning or significance to their lives. "I feel good when I think about what I have done in the past in this city and what I hope to do in the future” is an example of an item.

Each item on the CPBPU consists of six alternative responses in Likert format, and the assessment is as follows: strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), slightly disagree (3), slightly agree (4), agree (5), and strongly agree (6). The instrument items are contextualized with specific reference to Copiapó, Chile. Given the evolution that has been evident, for instance, through the development of new projects that have responded in line with urban growth based on the reproduction of capital and financial liquidity, it is relevant to study variables that seek to describe the quality of life of people in cities such as these (Rehner & Rodríguez, 2018). In this context, a previous study observed that various self-concepts regarding the city’s inhabitants made it possible to predict the perception of quality of urban life, finding no link between urban social identification and the perception of quality of life in Copiapó (Jorquera, 2012). In this sense, the construct and the proposed instrument enable progress in understanding the individual-city relationship from dimensions that point to personal development and growth in coexistence with the urban environment, which is increasingly dynamic and changing.

3.4. Procedure

The applications of the questionnaires were done in person with the inhabitants in various places in Copiapó, Atacama Region, Chile. Participants were invited to respond voluntarily. The purpose of the study and the confidential and reserved nature of the individual data collected were explained to them. The instruments were administered by a team of interviewers made up of university students trained for these purposes. The application lasted approximately five minutes with each participant.

3.5. Analytic strategy

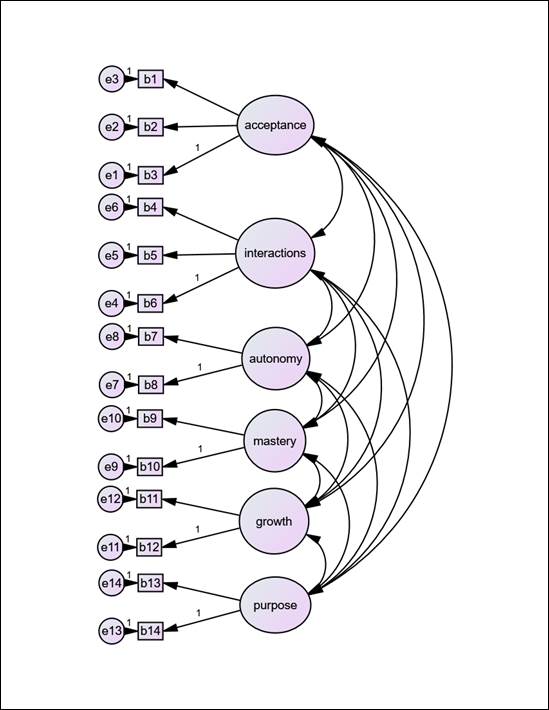

The psychometric properties of the instrument were first verified by a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient using the IBM SPSS 20.0 statistics package for Windows, while a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using the AMOS 18 program. This study sought to test the hypothesis that the instrument factor structure, based on a priori-defined construct, fits the data (see Figure 1). The goodness-of-fit of the scale was estimated using the maximum likelihood method. The indices considered in the CFAs were χ2, χ2/df, goodness-of-fit index (GFI), normed fit index (NFI), and comparative fit index (CFI). In addition, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was analyzed. For the cut-off points of these indicators, the recommendations of Hu and Bentler (1999) were considered, who proposed that when using maximum likelihood estimators, a cut-off value close to .95 for CFI and close to 0.06 for RMSEA is required. Values above .95 were considered optimal for GFI and NFI.

3.6. Ethical considerations

This study was approved and authorized by the university and the school of psychology authorities where it was conducted. It was part of a broader project to gather information on the quality of life and issues inherent to the city. The survey was applied by psychology students, who received an induction to perform the procedure. All necessary measures were taken to safeguard the well-being and integrity of the participants, following the ethical guidelines of the National Research and Development Agency (Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo [ANID], 2022). Participants were made aware of the study objectives, the anonymous nature of the research, and the voluntary nature of their participation. Data confidentiality was guaranteed at all times.

Figure 1.

Hypothetical model of the factor structure of the Perceived Urban Psychological Well-being Questionnaire

4. Results

4.1. Item analysis and reliability of scales

First, an analysis of the items was carried out. The highest mean is observed on the Prosocial Interaction scale (M = 4.63; SD=1.06), where its three items also have the highest means on the questionnaire. In contrast, the lowest mean is found on the Mastery of the Urban Environment scale (M = 4.32; SD = 1.17). All items on the instrument displayed negative skewness values and thus a tendency towards higher-ranked scores. Furthermore, all the absolute values are less than 1. The kurtosis of all the items has values of less than +-0.5. The inter-item correlation matrix shows that all the items correlate significantly with each other (p < .001). In the same way, a positive correlation of all items with each of their scales is noted. The scales that comprise the instrument have Cronbach’s alpha values between .783 and .874, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inter-item correlation matrix, descriptive statistics, and reliability for CPBPU scales and items

|

Item |

Inter-item correlations |

M (SD) |

Item-scale correlation |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

||

|

Self-acceptance (α = .87) |

|

|

4.40 (1.06) |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

|||||

|

1 |

1 |

.711** |

.620** |

4.35 (1.26) |

.715 |

-.858 |

.309 |

|

2 |

1 |

.746** |

4.38 (1.17) |

.807 |

-.701 |

.044 |

|

|

3 |

1 |

4.45 (1.14) |

.736 |

-.623 |

.181 |

||

|

Prosocial Interactions (α = .874) |

|

4.63 (1.06) |

|

|

|

||

|

|

4 |

5 |

6 |

||||

|

4 |

1 |

.726** |

.679** |

4.65 (1.17) |

.765 |

-.735 |

.059 |

|

5 |

1 |

.688** |

4.61 (1.18) |

.771 |

-.845 |

.466 |

|

|

6 |

1 |

4.64 (1.19) |

.737 |

-.764 |

.141 |

||

|

Autonomy (α = .857) |

|

|

4.33 (1.16) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

8 |

|||||

|

7 |

1 |

.750** |

4.36 (1.24) |

.750 |

-.573 |

-.190 |

|

|

8 |

|

1 |

|

4.30 (1.24) |

.750 |

-.502 |

-.367 |

|

Environmental Mastery (α = .783) |

|

4.32 (1.17) |

|

|

|

||

|

|

9 |

10 |

|||||

|

9 |

1 |

.643** |

4.40 (1.29) |

.643 |

-.587 |

-.200 |

|

|

10 |

1 |

|

4.24 (1.29) |

.643 |

-.824 |

.179 |

|

|

Personal Growth (α = .828) |

|

4.54 (1.08) |

|

|

|

||

|

|

11 |

12 |

|||||

|

11 |

1 |

.706** |

4.57 (1.16) |

.706 |

-.827 |

.487 |

|

|

12 |

|

1 |

|

4.52 (1.19) |

.706 |

-.854 |

.432 |

|

Purpose in Life (α = .847) |

|

4.48 (1.08) |

|

|

|

||

|

|

13 |

14 |

|||||

|

13 |

1 |

.735** |

4.51 (1.14) |

.735 |

-.724 |

.171 |

|

|

14 |

|

1 |

|

4.46 (1.18) |

.735 |

-.663 |

.053 |

Note: ** = The correlation is significant at the .01 level (bilateral); M = mean; SD = standard deviation.

4.2. Internal structure

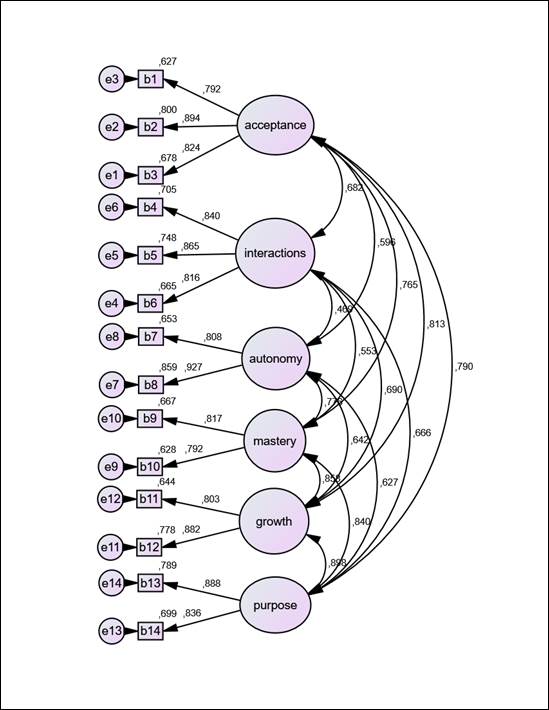

The scale adequately fit all the indices included in the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The Chi2 index was significant (χ2 = 141.143, df = 62, p<.001). The χ2/df ratio was less than 3 (2.276). The goodness-of-fit index (GFI), which measures the relative amount of variance explained by the model, showed an adequate value (GFI = .95). Also acceptable were the values obtained for the indices with which the relative fit of the model was evaluated — the normed fit index and comparative fit index — since both indices had values above .95 (NFI = .962 and CFI = .978). The fit of the model was also acceptable when considering the overall number of errors in the model, since the root mean square error of approximation had a value lower than .06 (RMSEA = .059).

All the factor loadings were significant, showing values between .792 and .927. In turn, their R2 behaved in ranges between .627 and .859.

Figure 2.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) of the Perceived Urban Psychological Well-being Questionnaire

5. Discussion and conclusions

The purpose of the study was to design and analyze the psychometric

characteristics of an instrument to measure Perceived Urban Psychological

Well-being. To achieve this, an instrument design with multimodal

characteristics was established, based on Ryff's proposal (1989a, 1989b), which

characterizes psychological well-being from a perspective related to positive

functioning and improving people's individual potential. However, the proposal

in this work included an ecological-environmental view of the construct. In

other words, the perceived urban psychological well-being is contextualized

from the spaces people inhabit, and from there, they develop judgments and

perceptions (Oviedo, 2002) regarding their well-being and quality of life.

In particular, the design of the proposed instrument considered the

urban subject as an individuality sustained in social settings and relations,

which determine and guide their symbolic representations and actions in a city

environment. In this sense, the CPBPU is in line with considering a subject to

be determined by specific relational spheres. Therefore, the analysis phase

begins by testing the hypothesis that the factors self-acceptance of the

context, prosocial interaction, context-facilitated autonomy,

context-facilitated mastery of the urban environment, context-facilitated

personal growth, and context-facilitated purpose in life fit the construct

defined as Perception of Urban Psychological Well-being. This is supported

first by the inter-item analysis, which shows a positive correlation of all the

items with each of their scales and the positive results obtained through the

confirmatory factor analysis. Moreover, the dimensions of the instrument

presented adequate Cronbach’s alpha reliability values. Therefore, the analysis

of the construct, its factors, and its items shows the CPBPU to be a reliable

and valid instrument.

This makes it possible to endorse, in the first instance, its use to

take measurements and make comparisons of the proposed construct and its

dimensions with various sociodemographic variables, thereby establishing trends

that merit examination in other urban contexts and expanding the body of

knowledge regarding predictor variables of the perception of psychological

well-being.

The challenge remains to verify the psychometric characteristics of the

instrument in other samples, cities, and/or regions to address the

particularities of diverse and specific groups such as encampments and migrant

populations. Similarly, the CPBPU is an instrument that could be used to verify

possible associations with emerging variables in urban populations, such as

perception of social support, functioning of social networks, feeling of

community, residential satisfaction, and others.

Percepción de bienestar psicológico urbano: Propiedades psicométricas de un instrumento de medición.

1. Introducción

El estudio del bienestar de las personas ha surgido como una temática de máximo interés en el último tiempo. Variadas son las intenciones, como también los enfoques y disciplinas desde las que se han realizado aproximaciones para medir un aspecto central de la calidad de vida de los habitantes de un territorio. Los primeros trabajos que se conocen al respecto estuvieron relacionados con el concepto de calidad de vida, donde disciplinas como la economía mostraron especial interés (Casas, 2010). Sin embargo, esto fue cambiando y el bienestar se comienza a asociar a indicadores psicosociales, como las relaciones interpersonales (Diener & Seligman, 2004), la predisposición de las personas ante las problemáticas sociales y los espacios que habitan, pues de acuerdo con la evidencia empírica, los contextos geográficos, sociales o culturales donde viven y participan los sujetos van modulando e influyendo en sus percepciones y acciones (Berry et al., 1992; Díaz, 2002).

Más específicamente, desde la Psicología Ambiental se viene estudiando la relación existente entre los espacios arquitectónicos y la percepción de bienestar de los habitantes de las ciudades. Al respecto, Hidalgo (2015) da cuenta que variados estudios empíricos constatan que algunos trastornos físicos y psicológicos estarían relacionados con la falta de contacto con la naturaleza de los habitantes urbanos, ante lo cual se propone modificar los diseños y características de las ciudades, en la lógica de crear ambientes más sostenibles y saludables, que permitan transformar los actuales estilos de vida marcados por la sobrecarga laboral e informativa, el sedentarismo y la falta de contacto con la naturaleza, factores que en última instancia permitirían la emergencia de sintomatologías físicas como del incremento de la presión arterial, trastornos hormonales y gástricos, alergias y obesidad (Daponte et al., 2015), sumado a la aparición de signos y síntomas psicológicos como la despersonalización, ansiedad, estrés, pérdida de la capacidad de atención, concentración y memoria (Hidalgo, 2015).

En este contexto, se puede analizar el concepto de Medio Ambiente Construido -MAC- que corresponde al entorno donde transcurre la vida de las personas (Daponte et al., 2015; Villanueva et al., 2012), cuyas características determinarían en gran medida la salud objetiva y la percepción de bienestar de los sujetos (Rahman et al., 2011). En particular, se relaciona de manera directa a las características y configuración urbana del MAC con la obesidad infantil (Kleinman, 2009; Villanueva et al., 2012) y una diversidad de problemas de salud pública que afectan al habitante urbano en la actualidad. En esa línea, la configuración de espacios urbanos poco amables y eficientes irían en sentido contrario al desarrollo de conductas prosociales y amigables en las ciudades (Gracida-Jiménez, 2015), lo cual tiene como consecuencia el favorecer procesos de distrés y alienación de los habitantes urbanos, a causa de la carencia de interacción prosocial.

Para la Organización Mundial de Salud (2003) el bienestar es un componente fundamental de la salud humana, tanto física como mental (Montoya & Landero, 2008). Ante ello, es clara la preocupación de la población por esta temática, sin embargo, es un constructo complejo de abordar, pues el bienestar puede entenderse desde la satisfacción de necesidades básicas de subsistencia, hasta necesidades y aspiraciones de autorrealización personal (Iñiguez & Olivera, 1994). En ese sentido, poder captar las percepciones de la población respecto a su bienestar psicológico, como indicador de calidad de vida, aparece como fundamental.

En esa línea, la Psicología, al analizar la percepción de bienestar, se ha movido entre dos tradiciones: por un lado, la tradición hedónica del bienestar representada por el constructo de bienestar subjetivo, asociado al concepto de felicidad, y, por otro lado, la tradición eudaimónica representada por el bienestar psicológico y relacionada con el potencial del desarrollo de las personas (Ryan & Deci, 2001). Sintéticamente, la tradición hedónica se sitúa en la lógica de la llamada psicología positiva, de ahí que este enfoque centre especial interés en el estudio de los afectos y la satisfacción con la vida (Cabañero et al., 2004) y como ello se relaciona con el bienestar humano. Mientras que la tradición eudaimónica tiene sus orígenes en la psicología humanista centrada en el desarrollo de las capacidades humanas y el crecimiento personal, de ahí que se articule en torno a conceptos como la autorrealización, funcionamiento pleno y madurez (Maslow, 1968; Rogers, 1961; Allport, 1961).

Con el objetivo de encontrar la convergencia de estas formulaciones teóricas, la psicóloga Carol Ryff (1989a, 1989b) hace un intento por ampliar e integrar en un constructo, dimensiones de orden social, subjetivo y psicológico, sumado a conductas relacionadas con la salud humana en general, las cuales propiciarían una manera positiva de funcionamiento de las personas. Así, Ryff (1989a, 1989b) define el concepto de bienestar psicológico, como el esfuerzo por perfeccionar el propio potencial, caracterizándolo como un constructo que representa el nivel de desarrollo psicológico de cada individuo, mientras interactúa de forma armoniosa y satisfactoria, con respecto a su entorno, así como con las actividades que realiza.

Ryff (1989a, 1989b) desarrolla una propuesta teórica que se traduce en un modelo multidimensional del bienestar psicológico, el cual estaría conformado por seis factores o dimensiones (Ryff & Keyes, 1995; Keyes et al., 2002): (a) Autoaceptación, relacionada con los sentimientos positivos que un individuo experimenta al sentirse satisfecho consigo mismo; (b) Relaciones positivas con los demás, vinculada a la priorización que realiza la persona por desarrollar relaciones estrechas con otros, asentadas en valores de confianza y empatía (Ortiz & Castro, 2009); (c) Autonomía, la cual implica sostener la propia individualidad en diferentes contextos sociales, factor que llevaría a que las personas logren asentar sus propias convicciones, en base a la autodeterminación, y así mantener su autoridad personal e independencia (Ryff & Keyes, 1995); (d) Dominio Ambiental, relacionada con la sensación de poder seleccionar e influir en el mundo de forma favorable de acuerdo a las propias necesidades y propósitos (Díaz et al., 2006); (e) Propósito en la vida, que conlleva una cohesión entre los esfuerzos y los retos del individuo, donde adquiere importancia el establecimiento de metas para luego deliberar en objetivos específicos que permitan otorgar un sentido o significado a la vida (Díaz et al., 2006); (f) Crecimiento personal, relacionada con llevar a un estado superior las propias potencialidades (Ortiz & Castro, 2009), por consiguiente, implica una actividad dinámica de aprendizaje en el cual se van desplegando las potencialidades que permite un desarrollo duradero de las fortalezas aplicadas y aprendidas (Keyes et al. 2002).

A partir de la propuesta de las seis dimensiones teóricas de Carol Ryff, se desarrollaron las Scales of Psychological Well-Being –SPWB-, cuyo punto más destacado, de acuerdo con Van Dierendonck (2004), es el procedimiento empleado en su construcción. En el inicio de este proceso participaron tres investigadores quienes propusieron 80 ítems por cada dimensión, de los cuales se seleccionaron 32, para finalmente reducirse a 20 ítems por dimensión, tras un estudio piloto con 321 adultos (Ryff, 1989b). Posteriormente, Ryff et al., (1994) desarrollaron una propuesta con 14 ítems por dimensión, para luego Ryff y Keyes (1995) proponer una versión de 3 ítems por dimensión, seleccionando aquéllos que de acuerdo con el estudio psicométrico mejor se ajustaban al modelo teórico de los seis factores. Finalmente, Keyes et al. (2002) desarrollan una versión de nueve ítems por dimensión.

En general, las estructuras factoriales de las SPWB, basadas en la propuesta de Ryff (1989a, 1989b), han sido verificadas mediante análisis factoriales confirmatorios –AFC-, centrándose el debate en la calidad de los modelos a partir de la cantidad de dimensiones o factores analizados (Véliz, 2012). Así es como Van Dierendonck (2004) con un estudio en población holandesa considera más adecuado el modelo de seis factores, a lo que tienden a coincidir Abbott et al., (2006) en un estudio con mujeres del Reino Unido. Mientras que Springer y Hauser (2006) en un estudio con población estadounidense concluyen que el modelo de los seis factores muestra deficiencias al presentar altas intercorrelaciones entre factores.

En población española, también se han estudiado las SPWB. Ejemplo de ello, son las investigaciones realizadas para estudiar el bienestar en el envejecimiento por Triadó (2003) y Navarro et al., (2007), donde se encuentran aceptables índices de fiabilidad en las escalas, aunque se critica lo extenso que resultan los cuestionarios al utilizar la versión de 14 ítems por factor. Pero es el trabajo de Díaz et al. (2006) realizado en el contexto español el que más se ha reconocido, pues aparte de traducir la versión de Van Dierendonck (2004), reduce la cantidad de ítems por factor generando una propuesta de 39 ítems en total, con lo cual se facilita su aplicación, alcanzando además aceptables criterios de validez y fiabilidad factorial, y buenos niveles de ajuste del modelo teórico de los seis factores (Díaz et al., 2006).

En el caso chileno, Véliz (2012) utiliza la versión traducida al español de Díaz et al. (2006) de 39 ítems y considerando los seis factores, en un estudio con 691 estudiantes universitarios de Temuco, en el que la escala presentó una aceptable confiabilidad destacando la dimensión Autoaceptación como la más alta (,79) y la más baja Propósito en la Vida (,54). El análisis factorial confirmatorio mostró un RMSEA aceptable de ,068, un valor CFI de ,95, un valor de NNFI ,94 y un SRMR con un valor de ,060. Tras estos resultados el autor concluye que el modelo tendría un ajuste adecuado, por lo que se permitiría su uso en la población universitaria chilena (Véliz, 2012).

Desde la perspectiva epistemológica, la propuesta del modelo multidimensional de bienestar psicológico o modelo integrado de desarrollo personal enfatiza el bienestar humano a partir del desarrollo de capacidades y el cumplimiento de objetivos que permiten el crecimiento de las personas (Romero et al., 2007). En esa perspectiva, el bienestar psicológico se ha centrado en indicadores de funcionamiento positivo y potencial humano, pero lo cierto, es que el constructo aparece mucho más complejo, multifacético y dinámico, por lo que necesita ser abordado desde otras dimensiones.

A modo de ejemplo, la Organización Mundial de la Salud en un intento por consensuar los diversos significados dados a la calidad de vida por las personas, establece que se trataría de la percepción que un individuo tiene de su lugar en la existencia, en el contexto de la cultura y del sistema de valores en los que vive y en relación con sus objetivos, sus expectativas, sus normas, sus inquietudes (The WHOQOL Group, 1995). De lo anterior se desprende que la calidad de vida es un constructo complejo y amplio, de manera tal, que el bienestar asociado a ella también es un concepto que reviste complejidad en su configuración, pues está asociado a los estados de salud física y psicológica, a los niveles de autonomía, relaciones interpersonales y con elementos de su entorno (Urzúa & Caqueo-Urizar, 2012), entre otras dimensiones que se destacan. Es así como la propuesta que realiza el presente trabajo considera la percepción del bienestar psicológico en su conexión con los espacios urbanos, entendiendo que estos también modulan las percepciones de bienestar humano.

En ese sentido, el bienestar psicológico urbano, debe entenderse focalizada a los espacios territoriales y urbanísticos que habitan las personas. Lo anterior, debido a que las condiciones en las que se vive en las ciudades, determinarían en gran medida pautas de organización territorial y comunitaria (Cueto et al., 2016) por una parte, pero también estas condiciones generarían actitudes y valores interpersonales que podrían provocar fenómenos psicosociales como frustración y agresividad, sumado a que ello definiría en última instancia, la percepción de las personas, respecto a su mundo social, al apoyo que reciben, a su calidad de vida y bienestar (Gracia & Herrero, 2006).

Como se aprecia, el bienestar de las personas se considera influido por diferentes variables, destacándose, entre otras, las sociodemográficas y el propio lugar en que habitan. De ahí entonces, que esta propuesta considera la percepción del bienestar psicológico urbano con una mirada contextuada, vale decir, considera que las personas se posicionan en sus contextos –en este caso, urbano- y desde ahí generan una autopercepción de bienestar, considerando que la evaluación subjetiva es un predictor relevante al momento de posicionar a un sujeto con sus recursos (Hicks et al., 2001). Desde esa perspectiva, la propuesta procura evaluar la percepción de los sujetos, pero en su interacción con el ambiente.

Considerando lo anterior, la percepción del bienestar urbano, se potencia desde perspectivas ecológico-ambientales, de ahí que considera elementos de la Psicología Ambiental, la cual otorga relevancia a los procesos psicológicos por los que las personas se adaptan a las exigencias del ambiente físico (Baldi & García, 2005), y del paradigma ecológico-contextual, cuya metáfora fundamental es el escenario que habitan las personas, el cual opera como conducta vivenciada y significativa para ellas (Lara & Lara, 2004). De esa manera, la percepción del bienestar urbano intenta establecer una relación dialéctica entre los contextos naturales que habitan las personas y la orientación subjetiva que de ello realizan.

Desde esa perspectiva, con el Cuestionario de Percepción del Bienestar Psicológico Urbano –CPBPU- se propone ubicar a las personas en interacción con su ambiente complejo, en este caso, el contexto urbano. Con ello, se buscaría brindar un concepto y un dispositivo de medición que permita favorecer el entendimiento de fenómenos y las maneras de relacionarse e incorporarse a las ciudades que presentan sus habitantes (Oviedo, 2002). De esa manera el sustento epistemológico del CPBPU, parte de la base que las personas establecen una relación activa con su entorno, desde donde emergen estados mentales que configuran juicios, percepciones, convicciones y creencias. Tal como señala Oviedo (2002, p. 27), “el sujeto en la ciudad construye representaciones simbólicas, crea imágenes mentales y diseña a nivel psíquico su propia perspectiva de la ciudad, con base en su capacidad de abstracción y delimitación de aspectos relevantes y orientadores”.

2. Objetivos

Tras lo señalado, la relevancia de la propuesta realizada viene dada por concebir que los habitantes de una ciudad van configurando espacios urbanos como representaciones internas, con las cuales interactúa simbólicamente con el entorno en que viven. De ahí que el CPBPU surge como una herramienta que podría llegar a facilitar la formulación de políticas públicas urbanas y el diseño urbanístico y arquitectónico. Ante ello, el objetivo de esta investigación es diseñar y analizar las características psicométricas de un instrumento para evaluar la Percepción del Bienestar Psicológico Urbano en población chilena. En términos específicos se busca: (a) construir un instrumento que permita dar respuesta al objeto de estudio señalado; (b) estudiar la consistencia interna de ítems y escala del instrumento; (c) estudiar la validez factorial del instrumento; (d) explorar y describir resultados iniciales levantados mediante el instrumento propuesto.

3. Método

En este apartado se describe la metodología usada en este estudio, desagregada en cinco secciones: diseño de investigación, participantes, instrumentos, procedimiento, y análisis de los datos.

3.1. Participantes

A través de un muestreo de tipo no probabilístico intencional, participaron voluntariamente 376 personas, todos habitantes de la ciudad de Copiapó, Región de Atacama. Según sexo, la distribución de la muestra estuvo constituida por un 51,1% de mujeres y un 48,9% de hombres. Respecto a las edades, un 27,9% (n = 105) eran personas de entre 18 y 29 años, el 49,7% (n = 187) tenían entre 30 y 49 años, y un 22,3% (n = 84) tenían más de 50 años. Según actividad, el 71,5% (n = 269) eran trabajadores activos, 11,7% (n = 44) estudiantes, 6,1% (n = 23) jubilados/pensionados, 3,7% (n = 14) cesantes, 6,1% (n = 23) dueñas de casa, 0,8% (n = 3) otro. Según nivel de ingreso familiar, y considerando valores en pesos chilenos (CLP), un 6,9% (n = 26) de los participantes declaró ingresos inferiores a $218.000, un 25,5% (n = 96) señalaron ingresos entre $218.000 y $440.000, un 41,5% (n = 151) dijeron poseer ingresos entre $440.000 y $670.000, un 23,7% (n = 89) declaró ingresos entre $670.000 y $1.800.000, un 1,3% (n = 5) indicó que sus ingresos familiares superaban $1.800.000, y 1,1% (n = 4) declinó entregar esta información. Según nivel educacional, un 10,9% (n = 41) de los participantes solo poseía estudios básicos-primarios completos, un 31,1% (n = 117) tenía estudios medios-secundarios completos, 33,2% (n = 125) poseía estudios técnico profesionales completos y un 24,5% (n = 92) tenía estudios universitarios completos.

3.2. Diseño

Se utilizó un diseño de tipo psicométrico o instrumental de acuerdo con la propuesta realizada por Ato et al. (2013), pues se persiguió diseñar y luego analizar las propiedades psicométricas del instrumento Cuestionario de Percepción del Bienestar Psicológico Urbano. Mientras que los datos fueron recolectados en un solo corte temporal, de ahí que se trata de un estudio transeccional.

3.3. Instrumentos

Con el objetivo de caracterizar a los participantes, se administró un breve cuestionario sociodemográfico, con variables dicotómicas y politómicas, en el cual se solicitaba informar sexo, edad, actividad, nivel de ingresos familiares y nivel educacional.

El instrumento Cuestionario de Percepción del Bienestar Psicológico Urbano –CPBPU-, toma como base la propuesta multimodal de las seis dimensiones teóricas de Carol Ryff (1989a, 1989b) pero las orienta a los contextos urbanos, desde una perspectiva ecológico-ambiental. En ese sentido, el CPBPU está conformado por 14 reactivos dirigidos a evaluar las seis dimensiones del constructo propuesto. La manera de construcción de los ítems fue mediante un procedimiento que partió de la teoría, en este caso, la propuesta multidimensional de Carol Ryff antes señalada, a partir de ella se realizó el ajuste del constructo de acuerdo con las pretensiones conceptuales señaladas, y posteriormente se construyeron los ítems (Perspectiva Top-Down).

Los factores que considera el instrumento son las siguientes:

a) Autoaceptación del contexto; orientado a establecer la autopercepción de satisfacción de las personas respecto al espacio urbano que habita, considerando su experiencia vital en éste. Se persigue obtener grados de identidad con la ciudad, estabilidad y proyecciones en este contexto urbano. Este factor se mide a partir de tres ítems tales como “cuando repaso la historia de mi vida en Copiapó, estoy contento con cómo se me han dado las cosas”.

b) Interacción prosocial; orientado a establecer la autopercepción de las personas respecto a las relaciones interpersonales de cercanía y confianza que ha desarrollado en el espacio urbano. Este factor se mide a partir de tres ítems como “en esta ciudad he logrado tener amigos íntimos con quienes compartir mis preocupaciones y alegrías”.

c) Autonomía facilitada por el contexto; orientado a establecer la autopercepción de las personas respecto a en qué medida el espacio urbano que habita le ha permitido crear y potenciar su identidad, autonomía, autoconfianza e individualidad, al punto de expresar opiniones y convicciones de manera resuelta y autónoma. Este factor se mide a partir de dos ítems como “en los contextos sociales en los que participo en la ciudad de Copiapó puedo expresar mis opiniones libremente, incluso cuando son opuestas a las opiniones de la mayoría de la gente”.

d) Dominio del entorno urbano; orientado a establecer la autopercepción de las personas en relación a cómo en el espacio urbano que habita ha podido agenciar su vida y desarrollar proyectos de acuerdo a sus necesidades y propósitos. Este factor se mide a partir de dos ítems tales como “en esta ciudad he sido capaz de construir un hogar y un modo de vida a mi gusto”.

e) Crecimiento Personal facilitado por el contexto; orientado a establecer la autopercepción de las personas respecto a cómo en el espacio urbano que habita ha podido aprender y desarrollarse. Este factor se mide a partir de dos ítems tales como “en el tiempo en que he vivido en Copiapó me he desarrollado mucho como persona”.

f) Propósito en la Vida facilitado por el contexto; orientado a establecer la autopercepción de las personas en relación a cómo en el espacio urbano que habita ha podido otorgar un sentido o significado de vida. Este factor se mide a partir de dos ítems tales como “me siento bien cuando pienso en lo que he hecho en el pasado en esta ciudad y lo que espero hacer en el futuro”.

Cada ítem del CPBPU consta de seis alternativas de repuesta en formato Likert, cuya valoración es la siguiente: muy en desacuerdo (1), en desacuerdo (2), ligeramente en desacuerdo (3), ligeramente de acuerdo (4), de acuerdo (5) y muy de acuerdo (6). Los ítems del instrumento se encuentran contextualizados haciendo referencia específica a la ciudad de Copiapó, Chile. Se hace relevante el estudio de variables que apuntan a describir la calidad de vida de las personas en ciudades como esta, dada la evolución que han ido manifestando, por ejemplo, a través del desarrollo de nuevos proyectos que han respondido a una lógica de crecimiento urbano en base a la reproducción del capital y a la liquidez financiera (Rehner & Rodríguez, 2018). En este contexto, en estudio previo se observó que diversos autoconceptos respecto a los habitantes de la ciudad permitían predecir la percepción de calidad de vida urbana, no encontrándose relación entre identificación social urbana y percepción de calidad de vida en la ciudad de Copiapó (Jorquera, 2012). En ese sentido, el constructo y el instrumento propuesto permiten avanzar en el entendimiento de la relación individuo-ciudad desde dimensiones que apuntan al desarrollo y crecimiento personal en convivencia con el entorno urbano, el cual cada vez es más dinámico y cambiante.

3.4. Procedimiento

Las aplicaciones de los cuestionarios se realizaron mediante acercamientos cara a cara con los habitantes en diversos puntos de la ciudad de Copiapó, Región de Atacama, Chile. Los participantes fueron invitados a responder voluntariamente, se les explicó el objetivo del estudio y el carácter confidencial y reservado de los datos individuales recolectados. Los instrumentos fueron administrados por un equipo de encuestadores conformados por estudiantes universitarios entrenados para tales fines. La duración promedio de la aplicación a cada participante fue de aproximadamente cinco minutos.

3.5. Análisis de datos

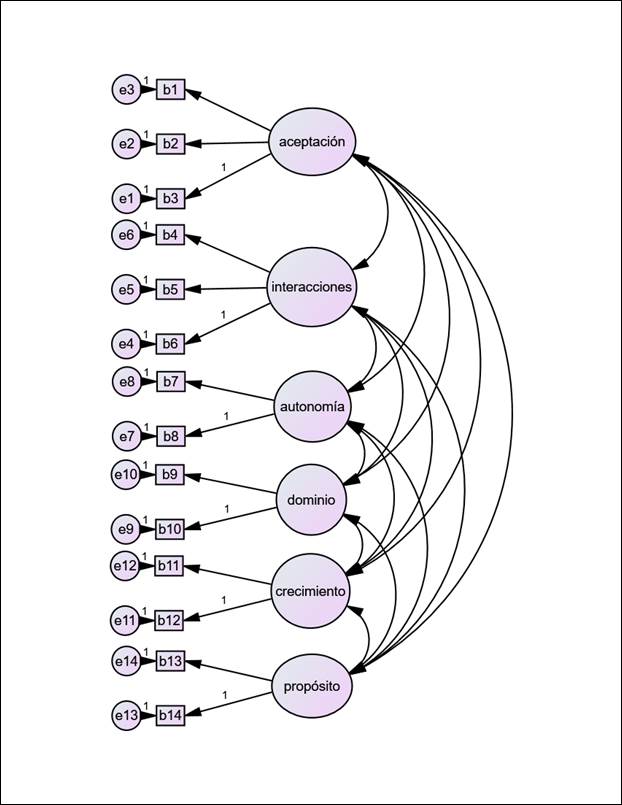

Las propiedades psicométricas del instrumento fueron constatadas, en primer lugar, mediante el estadígrafo alfa de Cronbach, utilizando el paquete estadístico IBM SPSS 20.0 para Windows, mientras que el Análisis Factorial Confirmatorio (AFC) se efectuó utilizando el programa AMOS 18. En el caso de la presente investigación, se buscó probar la hipótesis de que el comportamiento del instrumento se ajusta al constructo definido de manera a priori (Figura 1). La estimación de bondad de ajuste de la escala se llevó a cabo mediante el método de máxima verosimilitud. Los índices que se consideraron en los AFC fueron: χ2, razón χ2/gl, Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), el Normed Fit Index (NFI) y el Comparative Fit Index (CFI). Además, se analizó el Root Mean Square Error of Aproximation (RMSEA). Para los puntos de cortes de estos indicadores se consideraron las recomendaciones de Hu y Bentler (1999), quienes plantean que al usar estimadores de máxima verosimilitud se requiere un valor de corte cercano a .95 para CFI y uno cercano a 0,06 para RMSEA. Valores superiores a .95 se consideraron óptimos para GFI y NFI.

3.6. Consideraciones éticas

Este estudio contó con la aprobación y autorización de las autoridades de la universidad y de la escuela de psicología de en la cual se ejecutó. Fue parte de un proyecto más amplio que pretendía levantar información respecto a la calidad de vida y problemáticas propias de la ciudad. La aplicación de la encuesta fue realizada por estudiantes de psicología, quienes recibieron una inducción para efectuar el procedimiento. Se tomaron todas las medidas necesarias para resguardar el bienestar y la integridad de los participantes siguiendo las recomendaciones éticas de la Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID; 2022). Dentro de ello se explicitó a los participantes los objetivos de la investigación, el carácter anónimo de la misma y la voluntariedad de su participación. En este sentido, se garantizó en todo momento el resguardo de la confidencialidad de la información.

4. Resultados

4.1. Análisis de ítems y confiabilidad de escalas

En primer lugar, se realizó un análisis de los ítems. La media más alta se observa en la escala Interacción Prosocial (M = 4,63; DE=1,06), donde también sus tres ítems poseen las medias más altas del cuestionario. Por su parte, la media más baja se encuentra en la escala Dominio del Entorno Urbano (M = 4,32; DE = 1,17).

Con respecto a los valores de asimetría, todos los reactivos del instrumento presentaron una asimetría negativa y, por tanto, una tendencia hacia puntuaciones de rango superior. Además, la totalidad los valores absolutos son inferiores a 1. Por su parte, la curstosis de todos los elementos posee valores inferiores a +-0,5.

Figura 1.

Modelo Hipotético de la Estructura Factorial del Cuestionario de Percepción del Bienestar Psicológico Urbano

La matriz de correlaciones inter-elementos muestra que la totalidad de los ítems correlacionan entre ellos de manera significativa (p < ,001). De la misma forma, se aprecia una correlación positiva de todos los ítems con cada una de sus escalas. Las escalas que componen el instrumento presentan valores alfa de Cronbach entre ,783 y ,874 como se aprecia en la Tabla 1.

Tabla 1.

Matriz de correlaciones inter-elementos, estadísticos descriptivos y confiabilidad para las escalas e ítems del CPBPU.

|

Ítem |

Correlaciones inter-items |

M (DE) |

Correlación Ítem/escala |

Asimetría |

Curtosis |

||

|

Autoaceptación (α=,87) |

|

|

4,40 (1,06) |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

|||||

|

1 |

1 |

,711** |

,620** |

4,35 (1,26) |

,715 |

-,858 |

,309 |

|

2 |

1 |

,746** |

4,38 (1,17) |

,807 |

-,701 |

,044 |

|

|

3 |

1 |

4,45 (1,14) |

,736 |

-,623 |

,181 |

||

|

Interacciones Prosociales (α = ,874) |

|

4,63 (1,06) |

|

|

|

||

|

|

4 |

5 |

6 |

||||

|

4 |

1 |

,726** |

,679** |

4,65 (1,17) |

,765 |

-,735 |

,059 |

|

5 |

1 |

,688** |

4,61 (1,18) |

,771 |

-,845 |

,466 |

|

|

6 |

1 |

4,64 (1,19) |

,737 |

-,764 |

,141 |

||

|

Autonomía (α = ,857) |

|

|

4,33 (1,16) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

8 |

|||||

|

7 |

1 |

,750** |

4,36 (1,24) |

,750 |

-,573 |

-,190 |

|

|

8 |

|

1 |

|

4,30 (1,24) |

,750 |

-,502 |

-,367 |

|

Dominio del Entorno (α = ,783) |

|

4,32 (1,17) |

|

|

|

||

|

|

9 |

10 |

|||||

|

9 |

1 |

,643** |

4,40 (1,29) |

,643 |

-,587 |

-,200 |

|

|

10 |

1 |

|

4,24 (1,29) |

,643 |

-,824 |

,179 |

|

|

Crecimiento Personal (α = ,828) |

|

4,54 (1,08) |

|

|

|

||

|

|

11 |

12 |

|||||

|

11 |

1 |

,706** |

4,57 (1,16) |

,706 |

-,827 |

,487 |

|

|

12 |

|

1 |

|

4,52 (1,19) |

,706 |

-,854 |

,432 |

|

Propósito en la Vida (α = ,847) |

|

4,48 (1,08) |

|

|

|

||

|

|

13 |

14 |

|||||

|

13 |

1 |

,735** |

4,51 (1,14) |

,735 |

-,724 |

,171 |

|

|

14 |

|

1 |

|

4,46 (1,18) |

,735 |

-,663 |

,053 |

Nota: ** = La correlación es significativa al nivel ,01 (bilateral); M = media; DE = desviación estándar.

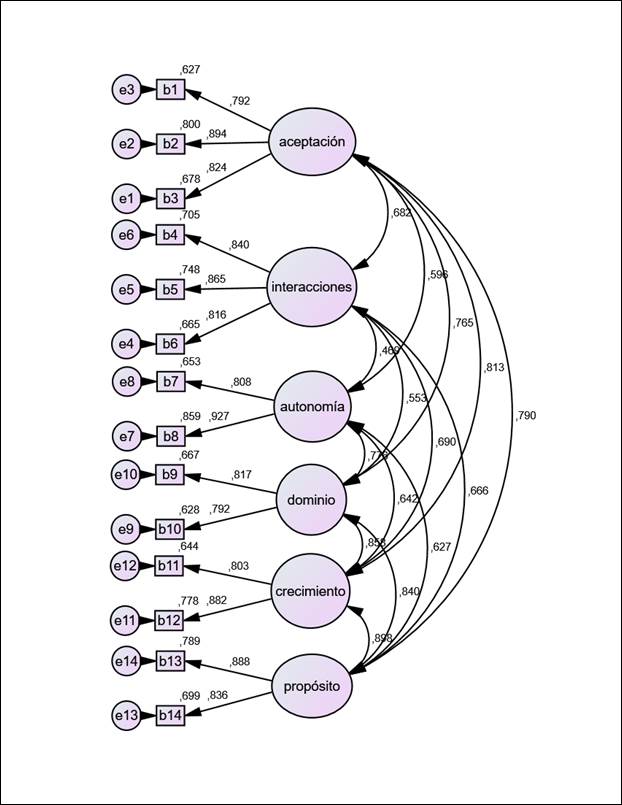

4.2. Estructura interna

La escala mostró un ajuste adecuado en todos los índices considerados en el análisis factorial confirmatorio (AFC). El índice χ2 resultó ser significativo (χ2 = 141,143, gl = 62, p < ,001). La razón χ2/gl fue inferior a 3 (2,276). El Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), que mide la cantidad relativa de varianza explicada por el modelo, mostró un valor adecuado (GFI = ,95). También fueron aceptables los valores obtenidos para los índices con los que se evaluó el ajuste relativo del modelo, Normed Fit Index y Comparative Fit Index, pues ambos índices presentaron valores superiores a ,95 (NFI = ,962 y CFI = ,978). El ajuste del modelo resultó también aceptable al considerar la cantidad global de error existente en el modelo, pues el Root Mean Square Errof of Aproximation presentó un valor inferior a ,06 (RMSEA = ,059). La totalidad de los pesos factoriales resultaron significativas, mostrando valores entre ,792 y ,927. A su vez, sus R2 se comportaron en rangos entre ,627 y ,859.

Figura 2.

Análisis Factorial Confirmatorio (AFC) del Cuestionario de Percepción del Bienestar Psicológico Urbano

5. Discusión y Conclusiones

El propósito del estudio fue diseñar y analizar las características psicométricas de un instrumento dirigido a medir la Percepción del Bienestar Psicológico Urbano. Para conseguir lo anterior se estableció un diseño de instrumento con características multimodales, referenciado en la propuesta de Ryff (1989a, 1989b), que caracteriza el bienestar psicológico desde una óptica relacionada al funcionamiento positivo y al perfeccionamiento del potencial individual de las personas. Sin embargo, la propuesta realizada en este trabajo consideró una mirada de orden ecológico-ambiental del constructo. Vale decir, que la percepción de bienestar psicológico urbano está contextualizada desde los espacios que habitan las personas, desde donde desarrollarían juicios y percepciones (Oviedo, 2002) respecto a su bienestar y calidad de vida.

En particular, el diseño del instrumento propuesto consideró al sujeto urbano, como una individualidad sustentada en contextos y relaciones sociales, que determinan y orientan sus representaciones simbólicas y sus acciones en el entorno de una ciudad. En ese sentido, el CPBPU se ajusta a la consideración de un sujeto determinado por ámbitos relacionales concretos. Por ello, en la fase de análisis se parte contrastando la hipótesis de que los factores autoaceptación del contexto, Interacción prosocial, autonomía facilitada por el contexto, dominio del entorno urbano, crecimiento personal facilitado por el contexto y propósito en la vida facilitado por el contexto, se ajustan al constructo definido como Percepción del Bienestar Psicológico Urbano. Lo anterior queda sustentado en primer lugar en el análisis inter-elementos realizado, donde se aprecia una correlación positiva de todos los ítems con cada una de sus escalas. A lo anterior se suman los resultados positivos obtenidos mediante el análisis factorial confirmatorio. Así también, las dimensiones del instrumento presentaron adecuados valores de confiabilidad alfa de Cronbach. Por lo anterior, el análisis del constructo, sus factores y elementos, demuestran que el CPBPU es un instrumento fiable y válido.

Lo anterior permitiría avalar, en primera instancia, su utilización para poder efectuar mediciones y comparaciones del constructo propuesto y sus dimensiones con diversas variables sociodemográficas, permitiendo establecer tendencias que merecen ser estudiadas en otros contextos urbanos, profundizando con ello el conocimiento de variables predictores de la percepción de bienestar psicológico.

Queda el desafío de verificar las características psicométricas del instrumento en otras muestras, en otras ciudades y/o regiones, con tal de atender a las particularidades de grupos diversos y también puntuales como, por ejemplo, campamentos y población migrante. De la misma manera, el CPBPU resulta un instrumento que podría ser utilizado para verificar posibles asociaciones con variables emergentes en las poblaciones urbanas, tales como percepción de apoyo social, funcionamiento de redes sociales, sentimiento de comunidad, satisfacción residencial, entre otras.

References

Abbott, R. A., Ploubidis, G. B., Huppert, F. A., Kuh, D., Wadsworth, M. E. J., & Croudace, T. J. (2006). Psychometric evaluation and predictive validity of Ryff's psychological well-being items in a UK birth cohort sample of women. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 4 (76), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-4-76

Allport, G. W. (1961). Pattern and growth in personality. Rinehart & Winston, Inc.

Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (2022). Lineamientos para la evaluación ética de la investigación en Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades. Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología, Conocimiento e Innovación, Chile. https://s3.amazonaws.com/documentos.anid.cl/proyecto-investigacion/Lineamientos-evaluacion-etica.pdf

Ato, M., López, J., & Benavente, A. (2013). Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. Anales de Psicología, 29(3), 1038-1059. https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.29.3.178511

Baldi, G., & García, E. (2005). Calidad de vida y medio ambiente. La psicología ambiental. Universidades, 30, 9-16. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=37303003

Berry, J., Poortinga, I., Segall, M., & Dasen, P. (1992). Cross-cultural psychology. Research and applications. Cambridge University Press.

Cabañero, M., Richard, M., Cabrero, J., Orts, M., Reig, A., & Tosal, B. (2004). Fiabilidad y validez de una Escala de Satisfacción con la Vida de Diener en una muestra de mujeres embarazadas y puérperas. Psicothema, 16(3), 448-455. https://reunido.uniovi.es/index.php/PST/article/view/8221

Casas, F. (2010). El bienestar personal: Su investigación en la infancia y la adolescencia. Encuentros en Psicología Social, 5, 85-101. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288230867_El_bienestar_personal_Su_investigacion_en_la_infancia_y_la_adolescencia

Cueto, R., Espinosa, A., Guillén, H., & Seminario, M. (2016). Sentido de Comunidad Como Fuente de Bienestar en Poblaciones Socialmente Vulnerables de Lima, Perú. Psykhe, 25(1), 1-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.7764/psykhe.25.1.814

Daponte, A., Ballesteros, V., Rueda de la Puerta, M., & Mateo, I. (2015). Medio ambiente construido y obesidad. In M. Aguilar-Luzón (Coord.), Avances de la Psicología Ambiental ante la promoción de la salud, el bienestar y La calidad de vida (pp. 48-49). Editorial Técnica Avicam.

Díaz, D., Rodríguez-Carvajal, R., Blanco, A., Moreno-Jiménez, B., Gallardo, I., Valle, C., & Dierendonck, D. (2006). Adaptación española de las escalas de bienestar psicológico de Ryff. Psicothema, 18(3), 572-577. https://www.psicothema.com/pi?pii=3255

Díaz, R. (2002). Atracción interpersonal: amigo y amantes. In C. Kimble, E. Hirt, R. Díaz, H. Hosch, G. W. Lucker, & M. Zarate (Eds.), Psicología Social de las Américas (pp. 291-369). Pearson Educación.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. (2004). Beyond Money. Towards an Economy of Well-Being. Psychological Science in the Public Forum, 5(1), 1-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00501001.x

Gracia, E., & Herrero, J. (2006). La comunidad como fuente de apoyo social: evaluación e implicaciones en los ámbitos individual y comunitario. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 38(2), 327-342. http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0120-05342006000200007

Gracida-Jiménez, B. (2015). La riqueza sensorial en el espacio existencial como facilitador de conductas de interacción prosocial. In M. Aguilar-Luzón (Coord.), Avances de la Psicología Ambiental ante la promoción de la salud, el bienestar y La calidad de vida (pp. 53-54). Editorial Técnica Avicam.

Hicks, J., Epperly, L., & Barnes, K. (2001). Gender, emotional support, and well-being among the rural elderly. Sex Roles, 45, 15-30. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013056116857

Hidalgo, M. (2015). Ambientes urbanos y salud física y mental. In M. Aguilar-Luzón (Coord.), Avances de la Psicología Ambiental ante la promoción de la salud, el bienestar y La calidad de vida (p. 50). Editorial Técnica Avicam.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Iñiguez, R., & Olivera S. (1994). Medio ambiente, condiciones de vida y salud. Un abordaje sobre la calidad de la vida en la región metropolitana de Río de Janeiro. FEEMA.

Jorquera, R. (2012). Autoconcepto e identificación social urbana en la ciudad de Copiapó, Chile. Summa Psicológica UST, 9(1), 33-46. https://doi.org/10.18774/448x.2012.9.73

Keyes, C., Ryff, C., & Shmotkin, D. (2002). Optimizing well-being: the empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 1007-1022. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.1007

Kleinman, R. (2009). Pediatric nutrition handbook. American Academy of Pediatrics.

Lara, J., & Lara, L. (2004). Recursos para un aprendizaje significativo. Enseñanza, 22, 341-368. https://revistas.usal.es/tres/index.php/0212-5374/article/view/4118

Maslow, A. H. (1968). Toward a psychology of being. D. Van Norstrand.

Montoya, B., & Landero, R. (2008). Satisfacción con la vida y autoestima en jóvenes de familias monoparentales y biparentales. Psicología y Salud, 18(1), 117-122. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/291/29118113.pdf

Navarro, E., Meléndez, J. C., & Tomás, J. M. (2007). Influencia de la edad en el bienestar de los mayores. Ponencia presentada en el 49 Congreso de la Sociedad Española de Geriatría y Gerontología, Palma de Mallorca, España.

Organización Mundial de la Salud. (2003). Informe sobre la salud en el mundo 2003. Forjemos el futuro. OMS. https://www.binasss.sa.cr/opac-ms/media/digitales/Informe%20sobre%20la%20salud%20en%20el%20mundo%202003.%20Forjemos%20el%20futuro.pdf

Ortiz, J., & Castro, M. (2009). Bienestar psicológico de los adultos mayores, su relación con la autoestima y la autoeficacia: contribución de enfermería. Ciencia y enfermería, 15(1), 25-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-95532009000100004

Oviedo, G. (2002). El estudio de la ciudad en la psicología ambiental. Revista de Estudios Sociales, 11, 26-34. https://journals.openedition.org/revestudsoc/27485

Rahman, T., Cushing, R., & Jackson, R. (2011). Contributions of Built Environment to Childhood Obesity. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, 78(1), 49-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/msj.20235

Rehner, J., & Rodríguez, S. (2018). La máquina de crecimiento en una ciudad minera y el papel del espacio público: el proyecto Parque Kaukari, Copiapó. Revista de Urbanismo, 38, 1-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.5354/0717-5051.2018.50434

Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person. Houghton Mifflin.

Romero, A., Brustad, R., & García, A. (2007). Bienestar psicológico y su uso en la psicología del ejercicio, la actividad física y el deporte. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología del Ejercicio y el Deporte, 2(2), 31-52. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3111/311126258003.pdf

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

Ryff, C. (1989a). Beyond Ponce de Leon and life satisfaction: New directions in quest of successful aging. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 12(1), 35-55. https://doi.org/10.1177/016502548901200102

Ryff, C. (1989b). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069-1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Ryff, C., Lee, Y. H., Essex, M. J., & Schmutte, P. S. (1994). My children and me: Midlife evaluations of grown children and of self. Psychology and Aging, 9(2), 195-205. https://doi.org/10.1037//0882-7974.9.2.195

Ryff, C., & Keyes, C. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719-727. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.719

Springer, K. V., & Hauser, R. M. (2006). An assessment of the construct validity of Ryff’s scales of psychological well-being: Method, mode and measurement effects. Social Science Research, 35(4), 1080-1102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2005.07.004

The WHOQOL Group. (1995). The World Health Organization Quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Social Science and Medicine, 41(10), 1403-1409. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-k

Triadó, M. C. (2003). Envejecer en entornos rurales. IMSERSO.

Urzúa, A., & Caqueo-Urízar, A. (2012). Calidad de vida: Una revisión teórica del concepto. Terapia Psicológica, 30(1), 61-71. https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48082012000100006

Van Dierendonck, D. (2004). The construct validity of Ryff’s Scale of Psychological well-being and its extension with spiritual well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(3), 629-644. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00122-3

Véliz, A. (2012). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Bienestar Psicológico y estructura factorial en universitarios chilenos. Psicoperspectivas, 11(2), 143-163. https://dx.doi.org/10.5027/psicoperspectivas-Vol11-Issue2-fulltext-196

Villanueva, K., Giles-Corti, B., Bulsara, M., McCormack, G., Timperio, A., Middleton, N., Beesley, B., & Trapp, G. (2012). How far do children travel from their homes? Exploring children's activity spaces in their neighborhood. Health & Place, 18(2), 263-273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.09.019

Statements

Author Contributions: Ricardo Jorquera conducted the empirical study, wrote the methodology, data analyses, and conclusions, and performed the general review of the article. Juan Rubio developed the article's theoretical framework, conclusions, and general review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.