|

|

Ibero-American Journal of Psychology and Public Policy eISSN 2810-6598 |

Research

Article |

Advertising impact on body image and self-esteem in Chilean women

(Impacto de la publicidad en la imagen corporal y autoestima de mujeres chilenas)

Raquel Corales 1, Millaray Correa 2, and José Luis Ulloa 3,*

1 Faculty of Psychology, Universidad de Talca, Chile; rcorales19@alumnos.utalca.cl

2 Faculty of Psychology, Universidad de Talca, Chile; mcorrea19@alumnos.utalca.cl

3 Centro de Investigación en Ciencias

Cognitivas (CICC), Faculty of Psychology, Universidad de Talca, Chile;

joseluisulloafulgeri@gmail.com ![]()

* Correspondence: joseluisulloafulgeri@gmail.com; phone number: +56712202518

|

Reference: Corales, R., Correa, M., & Ulloa, J. L. (2025). Advertising impact on body image and self-esteem in Chilean women (Impacto de la publicidad en la imagen corporal y autoestima de mujeres chilenas). Ibero-American Journal of Psychology and Public Policy, 2(2), 287-306. https://doi.org/10.56754/2810-6598.2025.0041 Editor: Carol Murray, Universidad de Antofagasta, Chile Reception date: 28 Mar 2025 Acceptance date: 14 Jul 2025 Publication date: 25 Jul 2025 Language: English and Spanish Translation: Helen Lowry Publisher’s Note: IJP&PP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Copyright: © 2025 by the authors. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY NC SA) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/). |

Abstract: Advertising plays a crucial role in people's lives by influencing their perceptions and choices. This influence can extend to how body image is perceived and ultimately affect self-esteem. This study focused on the impact of two types of advertising (stereotypical and inclusive) on Chilean women’s perception of body image and self-esteem. An experimental study was conducted with 39 participants divided into two groups exposed to different types of advertisements. The results revealed that stereotypical advertising negatively impacted body image perception but not self-esteem, whereas inclusive advertising had no impact. These findings support the need to promote responsible advertising practices in the media. Keywords: Stereotyped advertising; inclusive advertising; Latin America; wellbeing; physical appearance. Resumen: La publicidad desempeña un papel crucial en la vida de las personas al tener influencia en sus percepciones y elecciones. Esta influencia puede extenderse a la manera en que se percibe la imagen corporal y, eventualmente, afectar la autoestima. Esta investigación se enfocó en el impacto de dos tipos de publicidad (estereotipada e inclusiva) en la percepción de la imagen corporal y la autoestima de mujeres chilenas. Se llevó a cabo un estudio experimental con 39 participantes divididos en dos grupos, expuestos a diferentes tipos de videos publicitarios. Los resultados revelaron que la publicidad estereotipada tenía un efecto negativo significativo en la percepción de la imagen corporal pero no en la autoestima, mientras que la publicidad inclusiva no tenía un impacto. Estos hallazgos respaldan la necesidad de promover prácticas publicitarias responsables en los medios de comunicación. Palabras clave: Publicidad estereotipada; publicidad inclusiva; Latinoamérica; bienestar; apariencia física. Resumo: A publicidade desempenha um papel crucial na vida das pessoas ao influenciar suas percepções e escolhas. Essa influência pode se estender à forma como a imagem corporal é percebida e, eventualmente, afetar a autoestima. Esta pesquisa focou no impacto de dois tipos de publicidade (estereotipada e inclusiva) na percepção da imagem corporal e na autoestima de mulheres chilenas. Foi realizado um estudo experimental com 39 participantes divididas em dois grupos, expostas a diferentes tipos de vídeos publicitários. Os resultados revelaram que a publicidade estereotipada teve um efeito negativo significativo na percepção da imagem corporal, mas não na autoestima, enquanto a publicidade inclusiva não teve impacto. Esses achados reforçam a necessidade de promover práticas publicitárias responsáveis e uma imagem corporal positiva nos meios de comunicação. Palavras-chave: Publicidade estereotipada; publicidade inclusiva; América Latina; bem-estar; aparência física.

|

1. Introduction

Advertising is one of the main forms of persuasive communication in contemporary societies (Richards & Curran, 2002). Its primary objective is to promote products, services, or ideas by appealing to the emotions, aspirations, and needs of an audience to influence their consumption decisions and overall behavior (Soti, 2022). Through traditional media like television, magazines, and advertisements, as well as digital platforms such as websites and streaming services, advertising acts as a socialization agent that disseminates information while simultaneously constructing cultural meanings, identities, and values (Genner & Süss, 2017). Numerous studies have shown the varied effects of advertising on people's lives. On the one hand, advertising can have positive impacts by promoting healthy behaviors, supporting social causes, or raising awareness of relevant issues such as gender violence or environmental protection (Castelló-Martínez, 2024; Ribeiro Cardoso et al., 2023). On the other hand, advertising often generates messages that perpetuate gender stereotypes, reinforce restrictive ideals of beauty, and objectify the female body (Martín-Cárdaba et al., 2022).

These limited and idealized depictions endorse hegemonic standards of beauty that marginalize a significant portion of the population and exert a normative influence on women's appearance and behavior (Dai et al., 2025). The negative consequences of this sustained exposure to unattainable ideals have been explored in several dimensions. A correlation has been noted between exposure to stereotyped advertising content and the emergence of body dissatisfaction, decreased self-esteem, and emotional disorders (Castelló-Martínez, 2024; Fardouly et al., 2020; Grabe et al., 2008). Even brief exposure to advertisements featuring thin models with normative bodies can affect the subjective well-being of young women, increase upward social comparison, and trigger excessive concerns about physical appearance (Martín-Cárdaba et al., 2022). These effects are not restricted to a specific age group but are observed in both adolescents and adult women and are closely linked to mental health indicators such as anxiety, eating disorders, and depression (Fardouly et al., 2020; Grabe et al., 2008). Upward comparisons with idealized bodies, whether in static images or videos, reduce body satisfaction and increase thoughts of dieting and exercise; the effect is intensified when the figure displayed seems unattainable to the viewer (Fardouly et al., 2021; Gurtala & Fardouly, 2023). The emergence of the slim-thick ideal—a slender waist coupled with a voluptuous lower body—poses greater harm than the conventional thin ideal, particularly for women exhibiting elevated levels of physical perfectionism. Furthermore, repeated exposure to campaigns that perpetuate the thin ideal (e.g., Victoria's Secret) rapidly erodes self-esteem (McComb & Mills, 2022; Selensky & Carels, 2021).

In Latin America, aesthetic pressure merges the internalization of the ideal of thinness with a marked emphasis on curvaceous figures, although its intensity varies based on urban or rural settings, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity (Andres et al., 2024). Qualitative studies in rural Nicaraguan communities show that the low salience of a prescriptive ideal and the belief that the body is “a gift from God” act as protective factors against body dissatisfaction, despite increasing television exposure to soap operas and beauty pageants (Thornborrow et al., 2025). In Chile, empirical evidence of media influence on body perception is emerging.

A systematic review examining the Latin American population yielded inconclusive findings regarding the Chilean population (Andres et al., 2024). This review indicates that, among female university students, media pressure was moderately correlated with the aspiration for thinness, but not with muscle. In contrast, a study involving adolescents found no effect of media pressure on body dissatisfaction in either males or females. The sole qualitative study from Chile indicated that adolescent girls believe the media cultivates a local ideal defined by light-colored eyes and an hourglass figure, an ideal that fosters comparisons and discomfort in some. Chile's low representation in the literature—compared to the predominance of Brazil and Mexico—highlights the need for more research, particularly focusing on quantitative aspects.

To better understand the issue, it is useful to focus on two variables that appear to be central to the effects of advertising: self-esteem and body image. Self-esteem is the overall assessment a person makes of themself: how they perceive themself, what they believe about their own worth, and how much they trust their abilities (Rosenberg, 1965). An adequate level of self-esteem is essential for psychological and emotional well-being (Villalobos, 2019). Body image comprises the thoughts, memories, and feelings each individual has about their body’s appearance (Cash & Pruzinsky, 2004). Both constructs are particularly sensitive to the ideals of beauty promoted by the advertising industry. Numerous studies show that exposure to advertisements featuring models who embody unattainable standards tends to reduce self-esteem and increase body dissatisfaction (Hawkins et al., 2004). In female university students, for example, fashion advertisements featuring “perfect bodies” cause measurable declines in self-esteem and an increase in upward social comparison compared to neutral stimuli or stimuli without models (Craddock et al., 2019; Perloff, 2014).

A good benchmark for examining the negative effects of advertising is “no-stereotype advertising.” This form of advertising seeks to highlight diverse bodies and inclusive messages. Research indicates that advertisements featuring a variety of sizes, ages, and lifestyles generate more positive emotional responses, less concern about appearance, and even increases in self-esteem compared to traditional advertising (Diedrichs & Lee, 2011; Selensky & Carels, 2021). Therefore, these practices are a viable alternative to counteract the aforementioned negative effects (Dimitrieska et al., 2019).

Within this conceptual framework, this study seeks to provide empirical evidence on the effects of advertising on the body image and self-esteem of adult Chilean women. An experiment was conducted involving women aged 18 to 42, who were exposed to two categories of stimuli: stereotypical advertising videos (featuring conventional and limiting portrayals of beauty ideals) and inclusive videos (advocating body diversity and positive messages regarding self-image). Before and after exposure, participants completed two validated instruments: the Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Based on the literature reviewed, the main hypotheses are that exposure to stereotypical advertising will increase body dissatisfaction and decrease self-esteem levels (Hypothesis 1), and that inclusive advertising will decrease body dissatisfaction and increase self-esteem levels (Hypothesis 2). This study aims to enhance scientific knowledge of the psychosocial impacts of advertising while fostering dialogue on the need for tougher restrictions and the adoption of more responsible communication practices within the Chilean advertising sector.

2. Objective

Identify the effects of exposure to stereotypical and inclusive advertising on Chilean women's body image perception and self-esteem through a controlled experimental design.

3. Method

3.1 Participants

Thirty-nine adult women (M = 23.6, SD = 4.1, Range = 18–42 years) were recruited using non-probability convenience sampling. Since this study was conducted in the context of an undergraduate thesis to obtain a degree in psychology, participant recruitment was limited to the duration of this work. These constraints are also associated with its focus on university students and the measurement of the acute effects of exposure to advertising. Participants were recruited via social media and had to meet the requirements of being of legal age, identifying as female, and being Chilean nationals. Of the total number of women, 32 were students, 2 were homemakers, and 5 were workers.

3.2 Design

This study is a quantitative cross-sectional investigation with a mixed experimental design (with type of advertising as the inter-subject factor and moment in time as the intra-subject factor).

3.2.1 Stimuli

Ten fashion advertising videos obtained from YouTube were used, divided into two categories: stereotypical and inclusive, with five videos in each category. In the inclusive condition, advertising videos from the Corona and H&M stores (M = 37.2 s; SD = 23.4 s) were used, which show body diversity and convey messages that promote a positive body image. Specifically, the order of the videos and store information, campaign year, duration, and URL can be summarized as follows:

· H&M 2021, 49 s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ulZAO-Cnb-U

· H&M 2016, 72 s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8-RY6fWVrQ0

· Corona “Trajes” 2020, 15 s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5-vnClhhusc

· Corona “Jeans” 2023, 20 s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P0aemD6KvN8

· H&M 2023, 30 s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5BMwVJjCKTs

In the stereotypical condition, advertising videos from the clothing brands Victoria's Secret, Kendall, and Dolce & Gabbana (M = 44.2 s; SD = 43.6 s) were used, with audiovisual content that promotes restrictive body image norms and maintains a traditional ideal of beauty. The advertisements were:

· Victoria’s Secret 2013, 120 s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X3XRv75StUg

· Kendall 2023, 35 s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w2rOkLPm_Ic

· Dolce & Gabbana 2019, 36 s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kGdwiY_VWZY

· Victoria’s Secret 2016, 15 s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UPJHgtddYC4

· Victoria’s Secret “Dream” 2018, 15 s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VYzXXmpxz04

All the clips were downloaded in their original resolution (≥ 720p) with stereo audio, converted to .mp4 format, and presented sequentially in full-screen format on a black background. Each advertisement was given only once, and the order indicated above was maintained for all participants.

3.3 Instruments

3.3.1 Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ)

This questionnaire is used to measure body dissatisfaction and behaviors related to body image (Cooper et al., 1987). It consists of 34 questions about physical appearance and body image perception. Participants read each statement and respond according to whether they agree or disagree. The total score for the questionnaire is obtained by adding up the responses for each item. A high score indicates greater concern and dissatisfaction with one’s body. The questionnaire has a Cronbach's alpha of 0.95. There are no versions of this instrument adapted to the Chilean population. Therefore, a version adapted to Spanish was used, which was developed for university students by Raich et al. (1996).

3.3.2 Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965) consists of 10 affirmative or negative statements related to self-evaluation and sense of personal worth. Participants must indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree with each statement. Responses are scored on a four-point scale, which generally ranges from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” (Gray-Little et al., 1997). Once responses to all items have been collected, the scores are added together to obtain a total self-esteem score. A higher score indicates more positive self-esteem. This scale has a Cronbach's alpha of 0.78. The instrument translated and validated in Spanish for Chilean university students by Fernández et al. (2006) was used, which has adequate validity and reliability indices (Cronbach's alpha of 0.81).

3.4 Procedure and ethical safeguards

The study was conducted online using the Cognition platform

(cognition.run). Once the participants agreed to participate, they were sent a

link to access the experiment. First, they were presented with the informed

consent form explaining the purpose of the study and emphasizing the

confidentiality of the data and the voluntary nature of the entire process. Those

who agreed to continue had to click to move on to the next stage and fill in

their personal details. Participants were randomly allocated to two groups: one

exposed to stereotypical advertising videos (19 participants) and the other to

inclusive advertising videos (20 participants). Participants in both groups

were asked to complete two questionnaires: the Body Shape Questionnaire and

Rosenberg's Self-Esteem Scale. Once they had finished answering the

questionnaires, they were shown a set of advertising videos (inclusive or

stereotypical). After viewing the advertising videos, the participants

completed the questionnaires again. The participants required approximately 20

to 30 minutes to complete the experiment. This study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of the Faculty of Psychology at the University of Talca.

3.5 Analysis plan

A mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to assess the effect of the type of advertising (stereotypical or inclusive) at two points in time (before and after the presentation of the advertising) on body image perception and self-esteem. The analysis was performed using the R 4.3.2 statistics software (R Core Team, 2023).

4. Results

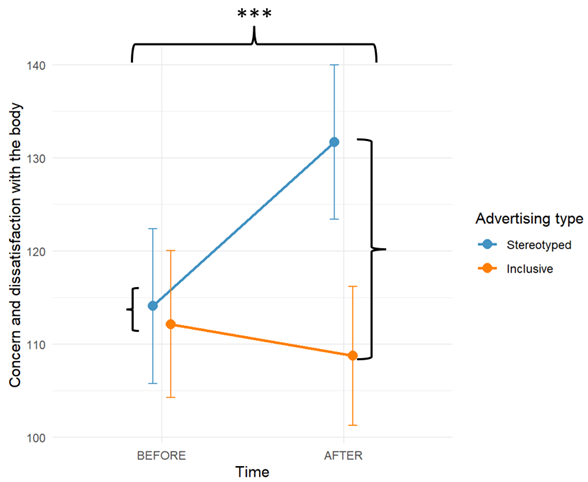

The average scores for body concern and dissatisfaction before and after viewing the stereotypical video were Mbefore = 114 (Standard Error [SE] = 8.31) and Mafter = 132 (SE = 8.30), respectively. In the case of the inclusive video, the average scores for body concern and dissatisfaction before and after were Mbefore= 112 (SE = 7.89) and Mafter = 109 (SE = 7.46), respectively. The ANOVA analysis showed a main effect of time, F(1, 37) = 6.11, p = .018, η2p = .142 (large effect), and a significant interaction between video type and time, F(1, 37) = 14.43, p < .001, η2p = .281 (large effect). No main effect of video type was observed, F(1, 37) = 1.29, p = .263, η2p = .034. The results presented in Figure 1 suggest that exposure to stereotypical advertising produces a negative perception of body image. Inclusive advertising did not change body shape perceptions.

Figure 1

Concern and dissatisfaction with body image before and after exposure to stereotypical and inclusive advertising

Note. The X-axis represents time (before and after), and the Y-axis represents the average score (and its standard error) on the body image questionnaire. The two types of advertising are shown: stereotypical and inclusive. The interaction effect with keys is emphasized. *** = p < .001.

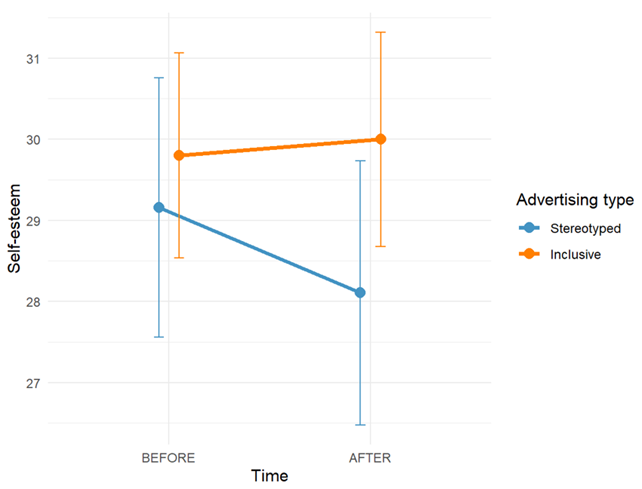

In the second analysis, the average self-esteem scores before and after viewing the stereotypical advertising were Mbefore = 29.2 (SE = 1.60) and Mafter = 28.1 (SE = 1.63), respectively. In inclusive advertising, the average self-esteem scores before and after were Mbefore = 29.8 (SE = 1.26) and Mafter = 30 (SE = 1.32). The ANOVA analysis showed no significant effects of video type, F(1, 37) = 0.41, p = .527, η2p = .011; time, F(1, 37) = 0.59, p = .449, η2p = .016; or their interaction, F(1, 37) = 1.37, p = .250, η2p = .036. These results are presented descriptively in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Self-esteem before and after exposure to stereotypical and inclusive advertising

Note. The X-axis represents time (before and after), and the Y-axis represents the average score (and its standard error) on the self-esteem questionnaire. The two types of advertising are shown: stereotypical and inclusive.

5. Discussion

This study explored the differential impact of stereotypical and inclusive advertising on the body image and self-esteem of adult Chilean women. The main result partially supports the first hypothesis, as there was a significant increase in body dissatisfaction among participants after exposure to stereotypical advertising. Conversely, the anticipated decline in self-esteem following exposure to stereotyped commercials was observed; however, the effect lacked statistical significance. This work has two central contributions. First, it extends the adverse effects of stereotypical advertising on body dissatisfaction to a Chilean sample—not previously studied in this context—replicating findings from research in Western populations (e.g., Grabe et al., 2008). Second, although the design has methodological limitations (e.g., small sample size), it is the first empirical approach to the phenomenon in Chile, laying the groundwork for future studies with greater statistical power and rigorous experimental controls. Despite their preliminary nature, these results highlight the urgent need for critical research into the role of advertising content in Latin America.

Contrary to the second hypothesis of the study, while exposure to inclusive advertisements reduces body concern and dissatisfaction and increases self-esteem, its effect was not statistically significant. This pattern of results diverges from some studies that report specific benefits of these messages (Diedrichs & Lee, 2011; Selensky & Carels, 2021) but aligns with reviews that highlight mixed effects: non-idealized models tend to be less harmful than idealized ones, although not necessarily restorative (De Lenne et al., 2023). The neutrality observed in self-esteem constitutes a critical null finding. Many assume that stereotypical advertising reduces self-esteem and inclusive advertising enhances it; however, the absence of changes suggests that self-esteem is a relatively stable construct and less sensitive than body image to brief, acute exposure (Orth & Robins, 2014). This raises questions about the dose and duration needed to influence self-esteem, or whether it depends more on social and relational factors than on isolated advertising. This is a factor that should be considered in future studies.

A key methodological aspect of this study was the interval between measurements. The pre-post measurements were applied immediately, so that the observed effect could be dominated by recency: the most recent information tends to be processed more intensely in immediate tests (Terry, 2005). Such proximity can amplify the impact of negative comparisons with hegemonic bodies and minimize any benefit from inclusive messages that require delayed cognitive processing. Studies with longer intervals between exposure and measurement have found different patterns. Another aspect that may explain the lack of impact of inclusive advertising has to do with certain biases. Negativity bias implies that when people compare themselves to hegemonic bodies, they generate negative emotions (e.g., dissatisfaction) that the brain records and remembers with greater intensity and duration than positive information (Baumeister et al., 2001; Rozin & Royzman, 2001). Therefore, brief exposure to inclusive advertising has difficulty counteracting the cumulative effect of years of upward comparisons with body ideals (Fardouly & Vartanian, 2016), which helps explain the lack of improvement observed in body image. Conversely, by assessing immediately after exposure, a recency effect may have been generated: the information presented last is processed more intensely and remembered better, thereby displacing other content (Glanzer & Cunitz, 1966; Murdock, 1962). This bias could have masked subtle variations that might have emerged after a longer interval of reflection and consolidation. Improvements reported in some studies are often associated with spaced measurements, which facilitate deeper cognitive processing and minimize short-term memory interference. Additionally, the effectiveness of body-positive content depends on repetition and on it being perceived as authentic; brief exposures or those read as a commercial strategy lose their impact (Mazzeo et al., 2024). It is not just about what is shown, but how often, for how long, and with what credibility. In summary, although there are several limitations (a small, homogeneous sample, immediate measurement, and lack of control over advertising exposure history), this study is a first step. Replicas with larger and more diverse samples, longitudinal designs, and repeated exposures are required to determine the dose and duration needed to influence self-esteem and body image.

Another important aspect to consider is whether the effect of advertising is related to what is shown or how and where it is shown. The format of the advertising message is crucial. Today, the consumption of visual content on networks like Instagram or TikTok surpasses traditional advertising in both prevalence and persuasive power: the immediacy of “likes” and comments intensifies self-objectification and upward comparisons and is already associated with greater body concerns and risky eating behaviors from pre-adolescence onwards (Fardouly et al., 2020; Vandenbosch et al., 2022). The relevance of these platforms is confirmed by the observation that just one week of digital abstinence is enough to improve self-esteem and body image (Smith et al., 2024). Attempts at regulation—such as warning labels about digital alterations—have proven ineffective and may inadvertently intensify the problem by reinforcing focus on idealized body representation (Blomquist et al., 2022). This dominant digital environment suggests that conventional advertising may have a comparatively smaller impact; however, the outlook varies across cultures: most studies come from the US and Europe, and there is little knowledge about Latin American realities, which underscores the need for local research (Dai et al., 2025). The lack of observed changes in self-esteem underscores its complex, multicausal nature—rooted in interpersonal dynamics, lived experiences, and contextual factors—thus necessitating an ecological framework that integrates proximal and social influences (Davison & Birch, 2001). Although the sample in this study is small and homogeneous, it offers an initial approach to the effects of advertising on Chilean women and reinforces the urgency of expanding the evidence with more diverse and culturally relevant designs. Finally, in Chile, the situation is worrying due to the lack of oversight. A report by the National Consumer Service (SERNAC) in 2024, which monitored advertising on 140 websites and 50 Instagram influencers, found that 35% of advertising was sexist. Current regulations lack binding criteria on body diversity and do not provide for specific penalties for hypersexualization. The paucity of local research combined with the high prevalence of body dissatisfaction and emotional disorders in young women underscores the urgency of evidence-based policies.

5.1 Recommendations for action

The findings suggest that stereotypical advertising immediately increases body dissatisfaction, while brief exposure to inclusive advertising is not sufficient to reverse it. Due to the limited and uniform size of the sample, these data should be regarded as a preliminary indication rather than an adequate justification for significant regulatory changes. With this caution in mind, three lines of action are proposed based on both this study and international literature (Gupta et al., 2023). Initiate public-private monitoring—including the National Television Council, SERNAC, and academia—to ensure that the validated sexism indicators are applied. Its initial purpose would be descriptive: to trace the frequency of stereotypes and publish open reports. Fines and certification seals (“No stereotype advertising”) should only be considered after repeated data confirming the magnitude of the problem has been ascertained. In addition, a critical analysis of advertisements and self-compassion exercises could be incorporated into pilot education programs (schools and universities). Prior to widespread adoption, each module should be assessed longitudinally to determine whether it reduces social comparisons and improves indicators of body well-being. Finally, mental health professionals can add brief screenings for body dissatisfaction and apply cognitive-behavioral interventions that challenge upward comparisons. Their recommendation is based on solid evidence of the effectiveness of these programs, not just on the present study. These actions are proportional to the scope of the findings and enable the modification of public policy as more robust local evidence is collected.

5.2 Limitations and future directions

This study had a small sample size that included mostly female university students, which limits its statistical power and the possibility of generalizing to other ages, educational levels, or body identities (Button et al., 2013; Henrich et al., 2010). The measurement was taken seconds after exposure, so the effects could be temporary and dominated by recency bias; no sustained impact can be inferred. Moreover, the lack of a sample size calculation renders it impossible to ascertain whether the absence of changes in self-esteem is attributable to the stability of the construct or insufficient statistical power. By relying exclusively on self-reports, physiological and behavioral responses that could complete the picture were not captured. Future studies should recruit more diverse samples, use repeated exposures in traditional media and social media with delayed follow-ups, and add psychophysiological measures. It is also advisable to explicitly manipulate the perceived authenticity of messages to determine whether this factor, together with the frequency of exposure, modulates the effects of inclusive advertising.

6. Conclusions

In this small, homogeneous Chilean sample, stereotypical advertising immediately increased body dissatisfaction, while inclusive advertising did not produce changes in either body image or self-esteem. These results confirm that idealized messages can adversely affect body well-being; however, they suggest that the mere presence of diverse bodies, in minimal doses, does not ensure positive outcomes. More extensive and longer-term studies are needed to determine whether repetition, perceived authenticity, and post-reflection time can make inclusive advertising an effective public health tool.

Impacto de la publicidad en la imagen corporal y autoestima de mujeres chilenas

1. Introducción

La publicidad constituye una de las principales formas de comunicación persuasiva en las sociedades contemporáneas (Richards & Curran, 2002). Su objetivo fundamental es promover productos, servicios o ideas, apelando a las emociones, aspiraciones y necesidades de una audiencia para influir en sus decisiones de consumo y en su comportamiento general (Soti, 2022). A través de medios tradicionales como la televisión, revistas y avisos publicitarios, y de canales digitales como sitios web y plataformas de contenido en línea (streaming), la publicidad se convierte en un agente de socialización que no solo difunde información, sino que también construye significados culturales, identidades y valores (Genner & Süss, 2017). Distintos estudios han mostrado los variados efectos de la publicidad sobre la vida de las personas. Por un lado, la publicidad puede generar impactos positivos al fomentar comportamientos saludables, apoyar causas sociales o visibilizar problemáticas relevantes como la violencia de género o el cuidado del medioambiente (Castelló-Martínez, 2024; Ribeiro Cardoso et al., 2023). Por otro lado, muchas veces la publicidad genera mensajes que perpetúan estereotipos de género, que refuerzan ideales de belleza restrictivos y que cosifican al cuerpo femenino (Martín-Cárdaba et al., 2022).

Estas representaciones limitadas e idealizadas promueven nociones hegemónicas de belleza que excluyen a gran parte de la población y que generan un efecto normativo sobre la forma en que las mujeres deben verse y comportarse (Dai et al., 2025). Las consecuencias negativas de esta exposición sostenida a ideales inalcanzables se han investigado en varias dimensiones. Se ha observado una relación entre la visualización de contenido publicitario estereotipado y la aparición de insatisfacción corporal, disminución de la autoestima y alteraciones emocionales (Castelló-Martínez, 2024; Fardouly et al., 2020; Grabe et al., 2008). Incluso exposiciones breves a anuncios que presentan modelos delgadas y con cuerpos normativos pueden afectar el bienestar subjetivo de mujeres jóvenes, aumentar la comparación social ascendente y detonar preocupaciones excesivas respecto a la apariencia física (Martín-Cárdaba et al., 2022). Estos efectos no se restringen a un grupo etario específico, sino que se observan tanto en adolescentes como en mujeres adultas, y están estrechamente vinculados a indicadores de salud mental como la ansiedad, los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria y la depresión (Fardouly et al., 2020; Grabe et al., 2008). Las comparaciones ascendentes con cuerpos idealizados, ya sea en imágenes estáticas o videos, reducen la satisfacción corporal y aumentan los pensamientos de dieta y ejercicio; el efecto se intensifica cuando la figura exhibida parece inalcanzable para la espectadora (Fardouly et al., 2021; Gurtala & Fardouly, 2023). Además, la irrupción del ideal slim-thick ―cintura estrecha y cuerpo voluminoso― resulta todavía más perjudicial que el canon delgado tradicional, sobre todo en mujeres con elevados rasgos de perfeccionismo físico, mientras que la exposición reiterada a campañas que refuerzan el ideal delgado (p. ej., Victoria’s Secret) disminuye la autoestima de forma inmediata (McComb & Mills, 2022; Selensky & Carels, 2021).

En América Latina la presión estética combina la internalización del ideal delgado con un marcado énfasis en la curvilineidad, aunque su intensidad varía según la zona sea urbana o rural, el nivel socioeconómico y la pertenencia étnica (Andres et al., 2024). Estudios cualitativos en comunidades rurales nicaragüenses muestran que la baja saliencia de un ideal prescriptivo y la creencia de que el cuerpo es “un don de Dios” actúan como factores protectores frente a la insatisfacción corporal, pese a la creciente exposición televisiva a telenovelas y certámenes de belleza (Thornborrow et al., 2025). En Chile la evidencia empírica sobre la influencia mediática sobre la percepción corporal es emergente.

En una revisión sistemática enfocado en población latinoamericana se encontró que en población chilena los hallazgos son mixtos (Andres et al., 2024). En esta revisión, entre universitarias, la presión de los medios se asoció de forma moderada con la búsqueda de delgadez, pero no con la musculatura. En contraste, un trabajo con adolescentes no halló efectos de la presión mediática sobre la insatisfacción corporal en hombres ni mujeres. El único estudio cualitativo chileno mostró que las adolescentes perciben que los medios moldean un ideal local caracterizado por ojos claros y una silueta reloj-de-arena, ideal que genera comparaciones y malestar en algunas de ellas. La baja representación de Chile en la literatura ―frente al predominio de Brasil y México― subraya la necesidad de más investigaciones y sobre todo que se enfoquen en aspectos cuantitativos.

Para comprender mejor el problema se podría focalizar en un par de variables que parecen ser centrales en los efectos de la publicidad: la autoestima y la imagen corporal. La autoestima es la valoración global que una persona hace de sí misma: cómo se percibe, qué cree sobre su propio valor y cuánto confía en sus capacidades (Rosenberg, 1965). Su adecuado nivel es esencial para el bienestar psicológico y emocional (Villalobos, 2019). Por otro lado, la imagen corporal comprende los pensamientos, recuerdos y sentimientos que cada individuo mantiene sobre el aspecto de su cuerpo (Cash & Pruzinsky, 2004). Ambos constructos resultan especialmente sensibles a los ideales de belleza difundidos por la industria publicitaria. Numerosos estudios demuestran que la exposición a anuncios con modelos que encarnan estándares inalcanzables tiende a reducir la autoestima y a incrementar la insatisfacción corporal (Hawkins et al., 2004). En mujeres universitarias, por ejemplo, los anuncios de moda protagonizados por “cuerpos perfectos” provocan descensos medibles en la autovaloración y aumentan la comparación social ascendente frente a estímulos neutros o sin modelos (Craddock et al., 2019; Perloff, 2014).

Un buen punto de comparación para investigar los efectos negativos de la publicidad lo constituye la “publicidad sin estereotipos”. Este tipo de publicidad busca visibilizar cuerpos diversos y mensajes inclusivos. La investigación indica que los anuncios con variedad de tallas, edades y estilos de vida generan respuestas emocionales más positivas, menor preocupación por la apariencia y hasta incrementos de autoestima en comparación con la publicidad tradicional (Diedrichs & Lee, 2011; Selensky & Carels, 2021). Estas prácticas constituyen, por tanto, una alternativa viable para contrarrestar los efectos negativos antes descritos (Dimitrieska et al., 2019).

Bajo este marco conceptual, el presente estudio busca aportar evidencia empírica sobre los efectos de la publicidad en la imagen corporal y la autoestima de mujeres chilenas adultas. Para ello, se diseñó un experimento en el que participaron mujeres entre 18 y 42 años, quienes fueron expuestas a dos tipos de estímulos: videos publicitarios estereotipados (con representaciones tradicionales y restrictivas del ideal de belleza), y videos inclusivos (que promueven diversidad corporal y mensajes positivos sobre la autoimagen). Antes y después de la exposición, las participantes completaron dos instrumentos validados: el Cuestionario de la Forma Corporal (BSQ) y la Escala de Autoestima de Rosenberg. En base a la literatura revisada, se plantean como hipótesis principales que la exposición a publicidad estereotipada aumentará la insatisfacción corporal y disminuirá los niveles de autoestima (Hipótesis 1), y que la publicidad inclusiva disminuirá la insatisfacción corporal y aumentará los niveles de autoestima (Hipótesis 2). Este trabajo busca no solo contribuir al conocimiento científico sobre los efectos psicosociales de la publicidad, sino también abrir un espacio de discusión sobre la necesidad de promover regulaciones más estrictas e incorporar prácticas comunicacionales más responsables en el ámbito publicitario chileno.

2. Objetivo

Identificar los efectos de la exposición a la publicidad estereotipada e inclusiva en la percepción de la imagen corporal y la autoestima de las mujeres chilenas a través de un diseño experimental controlado.

3. Método

3.1 Participantes

Se reclutaron 39 mujeres mayores de edad (M = 23,6; DE = 4,1; Rango = 18-42 años) mediante un muestreo no probabilístico y por conveniencia. Dado que este estudio se realizó en el contexto de una tesis de pregrado para obtener el título de Psicología, el reclutamiento de participantes se limitó a la duración de este trabajo. Estas limitaciones también se relacionan con su foco en estudiantes universitarias y la medición de los efectos agudos de la exposición a la publicidad. Las participantes fueron reclutadas vía redes sociales y debían cumplir con el requisito de ser mayor de edad, identificarse con el género femenino y tener nacionalidad chilena. Del total de mujeres 32 eran estudiantes, 2 dueñas de casa y 5 trabajadoras.

3.2 Diseño

El estudio corresponde a una investigación cuantitativa de tipo transversal con diseño experimental mixto (con tipo de publicidad como factor inter-sujeto y momento en el tiempo como factor intra-sujeto).

3.2.1 Estímulos

Se usaron 10 videos publicitarios de moda obtenidos de YouTube, distribuidos en dos condiciones: estereotipada e inclusiva, cada una con cinco videos. En la condición inclusiva se usaron videos publicitarios de las tiendas comerciales Corona y H&M (M = 37,2 s; DE = 23,4 s) que muestran diversidad corporal y transmiten mensajes que fomentan una imagen corporal positiva. Específicamente, el orden de los videos y la información de la tienda, año de la campaña, duración y dirección de los anuncios se puede resumir así:

· H&M 2021, 49 s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ulZAO-Cnb-U

· H&M 2016, 72 s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8-RY6fWVrQ0

· Corona “Trajes” 2020, 15 s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5-vnClhhusc

· Corona “Jeans” 2023, 20 s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P0aemD6KvN8

· H&M 2023, 30 s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5BMwVJjCKTs

En la condición estereotipada se usaron videos publicitarios de las marcas de ropa Victoria’s Secret, Kendall y Dolce & Gabbana (M = 44,2 s; DE = 43,6 s) con contenido audiovisual que promueve normas restrictivas con la imagen corporal y mantienen un ideal de belleza tradicional. Los anuncios fueron:

· Victoria’s Secret 2013, 120 s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X3XRv75StUg

· Kendall 2023, 35 s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w2rOkLPm_Ic

· Dolce & Gabbana 2019, 36 s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kGdwiY_VWZY

· Victoria’s Secret 2016, 15 s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UPJHgtddYC4

· Victoria’s Secret “Dream” 2018, 15 s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VYzXXmpxz04

Todos los clips se descargaron en su resolución original (≥ 720 p) con audio estéreo, se convirtieron al formato .mp4 y se presentaron a pantalla completa sobre fondo negro en forma concatenada. Cada anuncio se presentó sólo una vez y se mantuvo el orden indicado anteriormente para todas las participantes.

3.3 Instrumentos

3.3.1 Cuestionario de la Forma Corporal (BSQ)

Este cuestionario se utiliza para medir la insatisfacción corporal y los comportamientos relacionados con la imagen corporal (Cooper et al., 1987). Se compone de 34 preguntas sobre la apariencia física y la percepción de la imagen corporal. Los participantes deben leer cada información y responder según su acuerdo o desacuerdo. El puntaje total del cuestionario se obtiene sumando las respuestas de cada ítem. Un puntaje alto indica una mayor preocupación e insatisfacción con el cuerpo. El cuestionario cuenta con un Alfa de Cronbach de 0,95. Para este instrumento no hay versiones adaptadas a población chilena. Por lo tanto, se utilizó una versión adaptada al español que se realizó en estudiantes universitarias por Raich et al. (1996).

3.3.2 Escala de Autoestima de Rosenberg

La Escala de Autoestima de Rosenberg (Rosenberg, 1965) consta de 10 declaraciones afirmativas o negativas relacionadas con la autoevaluación y el sentido de valía personal. Los participantes deben indicar en qué medida están de acuerdo o en desacuerdo con cada declaración. Las respuestas se puntúan en una escala de cuatro puntos, que generalmente varía desde "totalmente en desacuerdo" hasta "totalmente de acuerdo" (Gray-Little et al., 1997). Una vez que se han recopilado las respuestas de todos los ítems, se suman los puntajes para obtener un puntaje total de autoestima. Un puntaje más alto indica una autoestima más positiva. Esta escala cuenta con un Alfa de Cronbach de 0,78. Se utilizó el instrumento traducido y validado en español en estudiantes universitarios chilenos por Fernández et al. (2006), la cual presenta adecuados índices de validez y confiabilidad (Alfa de Cronbach de 0,81).

3.4 Procedimiento y resguardos éticos

El estudio se realizó de forma online utilizando la plataforma Cognition (cognition.run). Una vez que las participantes estuvieron de acuerdo en participar se les envió un enlace para acceder al experimento. Primero se les presentó el consentimiento informado que explica el objetivo del estudio y recalca la confidencialidad de los datos y la voluntariedad a lo largo de todo el proceso. Quienes aceptaron continuar debieron hacer clic para pasar a la siguiente etapa y completar sus datos personales. Las participantes fueron asignadas aleatoriamente a dos grupos, uno que sería expuesto a videos publicidad estereotipada (19 participantes) y otro que sería expuesto a videos publicitarios inclusivos (20 participantes). A las participantes de ambos grupos se les solicitó a que respondieran dos cuestionarios: un Cuestionario de la Forma Corporal y la Escala de Autoestima de Rosenberg. Una vez que terminaron de contestar los cuestionarios fueron expuestas a un set de videos publicitarios (inclusivos o estereotipados). Después de la exposición a los videos publicitarios, las participantes completaron nuevamente los cuestionarios. Las participantes requirieron aproximadamente entre 20 a 30 minutos para completar el experimento. Este estudio contó con la aprobación del Comité de Ética de la Facultad de Psicología de la Universidad de Talca.

3.5 Plan de análisis

Se efectuó un análisis de varianza (ANOVA) mixto para evaluar el efecto del tipo de publicidad (estereotipada o inclusiva) en dos momentos en el tiempo (antes y después de la presentación de la publicidad) en la percepción de la imagen corporal y la autoestima. El análisis se realizó utilizando el software estadístico R 4.3.2 (R Core Team, 2023).

4. Resultados

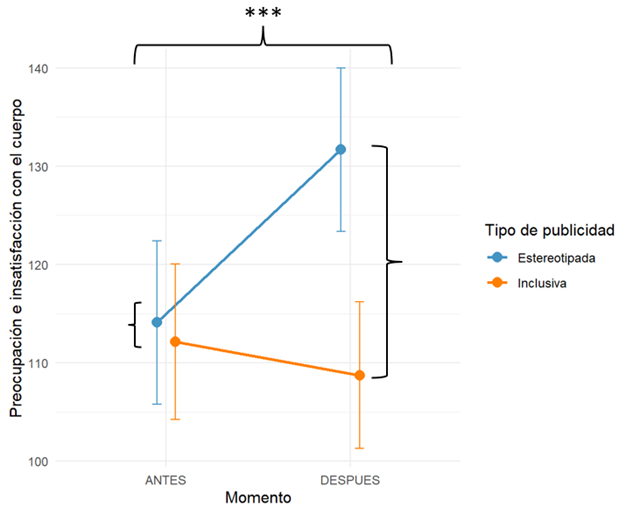

Los puntajes promedio de preocupación e insatisfacción con el cuerpo antes y después de ver el video estereotipado fueron Mantes = 114 (Error Estándar [EE] = 8,31) y Mdespués = 132 (EE = 8,30), respectivamente. En el caso del video inclusivo, los puntajes promedio de preocupación e insatisfacción con el cuerpo antes y después fueron Mantes = 112 (EE = 7,89) y Mdespués = 109 (EE = 7,46), respectivamente. El análisis de ANOVA mostró un efecto principal del tiempo, F(1, 37) = 6,11, p = ,018, η2p = ,142 (efecto grande), y una interacción significativa entre el tipo de video y el tiempo, F(1, 37) = 14,43, p < ,001, η2p = ,281 (efecto grande). No se observó un efecto principal del tipo de video, F(1, 37) = 1,29, p = ,263, η2p = ,034. Los resultados presentados en la Figura 1 sugieren que la exposición a publicidad estereotipada produce una percepción negativa de la imagen corporal. La publicidad inclusiva no produjo cambios en la percepción de la forma corporal.

Figura 1

Preocupación e insatisfacción con el cuerpo antes y después de la exposición a publicidad estereotipada e inclusiva

Nota. El eje X representa el momento (antes y después), y el eje Y representa el puntaje promedio (y su error estándar) en el cuestionario de imagen corporal. Se muestran los dos tipos de publicidad: estereotipada e inclusiva. Se enfatiza el efecto de interacción con las llaves. *** = p < ,001.

En el segundo análisis, los puntajes promedio de autoestima antes y después de visualizar la publicidad estereotipada fueron Mantes = 29,2 (EE = 1,60) y Mdespués = 28,1 (EE = 1,63), respectivamente. Por su parte, en la publicidad inclusiva los puntajes promedio de autoestima antes y después fueron Mantes = 29,8 (EE = 1,26) y Mdespués = 30 (EE = 1,32). El análisis de ANOVA no mostró efectos significativos del tipo de video, F(1, 37) = 0,41, p = ,527, η2p = ,011; del tiempo, F(1, 37) = 0,59, p = ,449, η2p = ,016; ni de su interacción, F(1, 37) = 1,37, p = ,250, η2p = ,036. Estos resultados se presentan descriptivamente en la Figura 2.

Figura 2

Autoestima antes y después de la exposición a publicidad estereotipada e inclusiva

Nota. El eje X representa el momento (antes y después), y el eje Y representa el puntaje promedio (y su error estándar) en el cuestionario de autoestima. Se muestran los dos tipos de publicidad: estereotipada e inclusiva.

5. Discusión

Este estudio exploró el impacto diferencial de la publicidad estereotipada e inclusiva en la imagen corporal y autoestima de mujeres chilenas adultas. El resultado principal respalda parcialmente la primera hipótesis, ya que hubo un incremento significativo en la insatisfacción corporal de las participantes tras la exposición a la publicidad estereotipada. Por contraparte, la reducción de la autoestima luego de ver anuncios estereotipados se dio en la dirección esperada, pero el efecto no fue significativo. Este trabajo tiene dos contribuciones centrales. Primero, extiende a una muestra chilena ―no estudiada previamente en este contexto― los efectos adversos de la publicidad estereotipada sobre la insatisfacción corporal, replicando hallazgos de investigaciones en poblaciones occidentales (p. ej., Grabe et al., 2008). Segundo, aunque el diseño presenta limitaciones metodológicas (p. ej., tamaño muestral reducido), constituye un primer acercamiento empírico al fenómeno en Chile, sentando bases para futuros estudios con mayor potencia estadística y controles experimentales rigurosos. Pese a su carácter preliminar estos resultados destacan la urgencia de investigar críticamente el rol de los contenidos publicitarios en América Latina.

Contrario a lo propuesto en la segunda hipótesis del trabajo, a pesar de que la exposición a anuncios inclusivos reduce la preocupación e insatisfacción corporal y aumenta la autoestima, su efecto no fue estadísticamente significativo. Este patrón de resultados se aparta de algunos estudios que describen beneficios puntuales de estos mensajes (Diedrichs & Lee, 2011; Selensky & Carels, 2021), pero coincide con revisiones que subrayan efectos mixtos: los modelos no idealizados suelen ser menos dañinos que los idealizados, aunque no necesariamente reparadores (De Lenne et al., 2023). La neutralidad observada en la autoestima constituye un hallazgo nulo crítico. Muchos asumirían que la publicidad estereotipada la reduce y que la inclusiva la eleva; sin embargo, la ausencia de cambios sugiere que la autoestima es un constructo relativamente estable y menos sensible a una exposición breve y aguda que la imagen corporal (Orth & Robins, 2014). Ello plantea interrogantes sobre la dosis y la duración necesarias para influir en la autoestima, o si esta depende más de factores sociales y relacionales que de la publicidad aislada. Este es un factor que debe ser considerado en futuros estudios.

Un aspecto metodológico clave en este trabajo fue el intervalo entre las mediciones. Las mediciones pre y post se aplicaron inmediatamente, de modo que el efecto observado pudo estar dominado por la recencia: la última información se procesa con mayor intensidad en test inmediatos (Terry, 2005). Tal proximidad puede amplificar la huella de comparaciones negativas con cuerpos hegemónicos y minimizar cualquier beneficio de mensajes inclusivos que requieren reflexión diferida. Estudios que intercalan un intervalo más largo entre exposición y medición han hallado patrones diferentes. Otro aspecto que puede explicar la ausencia de efectos de la publicidad inclusiva tiene que ver con ciertos sesgos. El sesgo de negatividad implica que cuando las personas se comparan con cuerpos hegemónicos generan emociones negativas (p. ej., insatisfacción) que el cerebro graba y recuerda con más intensidad y duración que la información positiva (Baumeister et al., 2001; Rozin & Royzman, 2001). Por eso, una exposición breve a publicidad inclusiva tiene dificultades para contrarrestar el efecto acumulado de años de comparaciones ascendentes con ideales corporales (Fardouly & Vartanian, 2016), lo que ayuda a explicar la falta de mejora observada en la imagen corporal. Por otro lado, al evaluar inmediatamente después de la exposición, es posible que se haya generado un efecto de recencia: la información presentada en último lugar se procesa con mayor intensidad y se recuerda mejor, desplazando otros contenidos (Glanzer & Cunitz, 1966; Murdock, 1962). Este sesgo podría haber enmascarado variaciones sutiles que habrían emergido tras un intervalo más prolongado de reflexión y consolidación. Estudios que han encontrado mejoras suelen espaciar la medición, lo que favorece un procesamiento más profundo y reduce la interferencia de la memoria a corto plazo. Además, la efectividad del contenido body-positive depende de la repetición y de que se perciba como auténtico; exposiciones breves o leídas como estrategia comercial pierden impacto (Mazzeo et al., 2024). No se trata solo de qué se muestra, sino de con qué frecuencia, durante cuánto tiempo y con qué credibilidad. En síntesis, aunque existen varias limitaciones (una muestra pequeña y homogénea, una medición inmediata y la falta de control sobre la historia de exposición publicitaria) este estudio es un primer paso. Se requieren réplicas con muestras más grandes y diversas, diseños longitudinales y exposiciones repetidas para delimitar la dosis y duración necesarias para influir en la autoestima e imagen corporal.

Otro aspecto importante sobre el cual es importante reflexionar es si el efecto de la publicidad está relacionado en qué se muestra o cómo y dónde se muestra. El formato del mensaje publicitario es decisivo. Hoy, el consumo de contenido visual en redes como Instagram o TikTok supera en presencia y poder persuasivo a la publicidad tradicional: la inmediatez de los “me gusta” y los comentarios intensifica la autoobjetivación y las comparaciones ascendentes, y ya se asocia a mayor preocupación corporal y conductas alimentarias de riesgo desde la preadolescencia (Fardouly et al., 2020; Vandenbosch et al., 2022). La relevancia de estas plataformas se confirma al observar que basta una semana de abstinencia digital para mejorar autoestima e imagen corporal (Smith et al., 2024). Intentos regulatorios, como las etiquetas que advierten retoques, no mitigan el problema e incluso pueden empeorarlo al dirigir la atención hacia los cuerpos idealizados (Blomquist et al., 2022). Este entorno digital dominante sugiere que la publicidad convencional podría tener un impacto comparativamente menor, pero el panorama varía según la cultura: la mayoría de los estudios proceden de EE. UU. y Europa, y existe poco conocimiento sobre realidades latinoamericanas, lo que subraya la necesidad de investigación local (Dai et al., 2025). Además, la ausencia de cambios en la autoestima observada aquí refleja la naturaleza multicausal de este constructo ―dependiente de relaciones, experiencias y contexto― por lo que requiere un enfoque ecológico que considere el entorno inmediato y social (Davison & Birch, 2001). Aunque la muestra del presente trabajo es pequeña y homogénea, ofrece un primer acercamiento a los efectos publicitarios en mujeres chilenas y refuerza la urgencia de ampliar la evidencia con diseños más diversos y culturalmente pertinentes. Por último, en Chile, la situación es preocupante por la escasa fiscalización. Un informe del Servicio Nacional del Consumidor (SERNAC) en 2024 donde se realizó un monitoreo de la publicidad de 140 sitios web y a 50 influencers de Instagram, detectó que el 35% de la publicidad resultó ser sexista. La actual normativa carece de criterios vinculantes sobre diversidad corporal y no contempla sanciones específicas a la hipersexualización. La escasez de investigaciones locales unida a la alta prevalencia de insatisfacción corporal y trastornos emocionales en mujeres jóvenes subraya la urgencia de políticas basadas en evidencia.

5.1 Recomendaciones para la acción

Los hallazgos sugieren que la publicidad estereotipada eleva de inmediato la insatisfacción corporal, mientras que una exposición breve a publicidad inclusiva no basta para revertirla. Dado el tamaño reducido y homogéneo de la muestra, estas conclusiones deben tomarse como una señal preliminar y no como base suficiente para cambios regulatorios extensos. Con esa cautela, proponemos tres líneas de acción que se apoyan tanto en este trabajo como en la literatura internacional (Gupta et al., 2023). Iniciar un monitoreo público-privado —que incluya al Consejo Nacional de Televisión, al SERNAC y a la academia— para que se apliquen los indicadores de sexismo ya validados. Su propósito inicial sería descriptivo: trazar la frecuencia de estereotipos y publicar reportes abiertos. Multas y sellos de certificación (“Publicidad sin Estereotipos”) deberían considerarse solo tras contar con datos repetidos que confirmen la magnitud del problema. Por otro lado, se podría incorporar un análisis crítico de anuncios y ejercicios de autocompasión en planes educativos piloto (escuelas y universidades). Antes de una adopción masiva, cada módulo debiera evaluarse longitudinalmente para determinar si reduce comparaciones sociales y mejora indicadores de bienestar corporal. Por último, los profesionales de salud mental pueden añadir tamizajes breves de insatisfacción corporal y aplicar intervenciones cognitivo-conductuales que desafíen comparaciones ascendentes. Su recomendación se fundamenta en la evidencia sólida sobre la eficacia de estos programas, no únicamente en el presente estudio. Estas acciones son proporcionales al alcance de los hallazgos y permiten ir ajustando la política pública a medida que se acumule evidencia local más robusta.

5.2 Limitaciones y líneas futuras

Este estudio contó con un tamaño muestral reducido que incluyó en su mayoría mujeres universitarias, lo que restringe la potencia estadística y la posibilidad de generalizar a otras edades, niveles educativos o identidades corporales (Button et al., 2013; Henrich et al., 2010). La medición se realizó segundos después de la exposición, de modo que los efectos podrían ser transitorios y dominados por el sesgo de recencia; no se infiere un impacto sostenido. Además, la ausencia de un cálculo de tamaño muestral impide saber si la falta de cambios en autoestima se relaciona con la estabilidad del constructo o con baja potencia. Al basarse exclusivamente en autoinformes no se captaron respuestas fisiológicas ni conductuales que completarían el cuadro. Futuros trabajos deberían reclutar muestras más diversas, emplear exposiciones repetidas en medios tradicionales y redes sociales con seguimientos diferidos y añadir medidas psicofisiológicas. También conviene manipular explícitamente la autenticidad percibida de los mensajes para determinar si este factor, junto con la frecuencia de exposición, modula los efectos de la publicidad inclusiva.

6. Conclusiones

En esta muestra chilena pequeña y homogénea la publicidad estereotipada aumentó la insatisfacción corporal de forma inmediata, mientras que la publicidad inclusiva no produjo cambios ni en imagen corporal ni en autoestima. Estos resultados confirman que los mensajes idealizados pueden dañar el bienestar corporal, pero indican que la sola presencia de cuerpos diversos, en dosis mínimas, no garantiza beneficios. Se necesitan estudios más amplios y prolongados que determinen si la repetición, la autenticidad percibida y el tiempo de reflexión posterior pueden convertir la publicidad inclusiva en una herramienta efectiva de salud pública.

References

Andres, F. E., Boothroyd, L. G., Thornborrow, T., Chamorro, A. M., Dutra, N. B., Brar, M., Woodward, R., Malik, N., Sawhney, M., & Evans, E. H. (2024). Relationships between media influence, body image and sociocultural appearance ideals in Latin America: A systematic literature review. Body Image, 51, 101774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2024.101774

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is Stronger than Good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323–370. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.5.4.323

Blomquist, K. K., Pate, S. P., Hock, A. N., & Austin, S. B. (2022). Evidence-based policy solutions to prevent eating disorders: Do disclaimer labels on fashion advertisements mitigate negative impact on adult women? Body Image, 43, 180–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.08.010

Button, K. S., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Mokrysz, C., Nosek, B. A., Flint, J., Robinson, E. S. J., & Munafò, M. R. (2013). Power failure: Why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(5), 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3475

Cash, T. F., & Pruzinsky, T. (Eds.). (2004). Body Image: A Handbook of Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice (First Edition). The Guilford Press.

Castelló-Martínez, A. (2024). Social commitment and sustainability in the award-winning campaigns at advertising festivals [Compromiso social y sostenibilidad en las campañas premiadas en festivales publicitarios]. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación/Mediterranean Journal of Communication, 15(2), e25977. https://doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM.25977

Cooper, P. J., Taylor, M. J., Cooper, Z., & Fairbum, C. G. (1987). The development and validation of the body shape questionnaire. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 6(4), 485–494. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(198707)6:4<485::AID-EAT2260060405>3.0.CO;2-O

Craddock, N., Ramsey, M., Spotswood, F., Halliwell, E., & Diedrichs, P. C. (2019). Can big business foster positive body image? Qualitative insights from industry leaders walking the talk. Body Image, 30, 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.06.004

Dai, Y., Zhu, Z., & Yuan Guo, W. (2025). The impact of advertising on women’s self-perception: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1430079. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1430079

Davison, K. K., & Birch, L. L. (2001). Childhood overweight: A contextual model and recommendations for future research. Obesity Reviews, 2(3), 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00036.x

De Lenne, O., Vandenbosch, L., Smits, T., & Eggermont, S. (2023). Experimental research on non-idealized models: A systematic literature review. Body Image, 47, 101640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2023.101640

Diedrichs, P. C., & Lee, C. (2011). Waif goodbye! Average-size female models promote positive body image and appeal to consumers. Psychology & Health, 26(10), 1273–1291. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2010.515308

Dimitrieska, S., Stamevska, E., & Stankovska, A. (2019). Inclusive Marketing – Reality Or Make Up. Economics and Management, 16(2), 112–119. https://ideas.repec.org/a/neo/journl/v16y2019i2p112-119.html

Fardouly, J., Magson, N. R., Rapee, R. M., Johnco, C. J., & Oar, E. L. (2020). The use of social media by Australian preadolescents and its links with mental health. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(7), 1304–1326. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22936

Fardouly, J., Pinkus, R. T., & Vartanian, L. R. (2021). Targets of comparison and body image in women’s everyday lives: The role of perceived attainability. Body Image, 38, 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.04.009

Fardouly, J., & Vartanian, L. R. (2016). Social Media and Body Image Concerns: Current Research and Future Directions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 9, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.09.005

Fernández, A. M., Celis Atenas, K., & Vera Villarroel, P. (2006). Propiedades psicométricas de la escala de autoestima de Rosenberg en universitarios chilenos [Poster presentation]. In Memorias de las XIII Jornadas de Investigación y Segundo Encuentro de Investigadores en Psicología del Mercosur (pp. 499–500). Facultad de Psicología, Universidad de Buenos Aires. http://jimemorias.psi.uba.ar/index.aspx?anio=2006

Genner, S., & Süss, D. (2017). Socialization as Media Effect. In P. Rössler, C. A. Hoffner, & L. Zoonen (Eds.), The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects (1st ed., pp. 1–15). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0138

Glanzer, M., & Cunitz, A. R. (1966). Two storage mechanisms in free recall. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 5(4), 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(66)80044-0

Grabe, S., Ward, L. M., & Hyde, J. S. (2008). The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin, 134(3), 460–476. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.460

Gray-Little, B., Williams, V. S. L., & Hancock, T. D. (1997). An Item Response Theory Analysis of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(5), 443–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167297235001

Gupta, A., Raine, K. D., Moynihan, P., & Peres, M. A. (2023). Australians support for policy initiatives addressing unhealthy diet: a population-based study. Health Promotion International, 38(3), daad036. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daad036

Gurtala, J. C., & Fardouly, J. (2023). Does medium matter? Investigating the impact of viewing ideal image or short-form video content on young women’s body image, mood, and self-objectification. Body Image, 46, 190–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2023.06.005

Hawkins, N., Richards, P. S., Granley, H. M., & Stein, D. M. (2004). The Impact of Exposure to the Thin-Ideal Media Image on Women. Eating Disorders, 12(1), 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640260490267751

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

Martín-Cárdaba, M. A., Porto-Pedrosa, L., & Verde-Pujol, L. (2022). Representación de la belleza femenina en publicidad. Efectos sobre el bienestar emocional, la satisfacción corporal y el control del peso en mujeres jóvenes. Profesional de la información, 31(1), e310117. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2022.ene.17

Mazzeo, S. E., Weinstock, M., Vashro, T. N., Henning, T., & Derrigo, K. (2024). Mitigating Harms of Social Media for Adolescent Body Image and Eating Disorders: A Review. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 17, 2587–2601. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S410600

McComb, S. E., & Mills, J. S. (2022). The effect of physical appearance perfectionism and social comparison to thin-, slim-thick-, and fit-ideal Instagram imagery on young women’s body image. Body Image, 40, 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.12.003

Murdock, B. B. (1962). The serial position effect of free recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 64(5), 482–488. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045106

Orth, U., & Robins, R. W. (2014). The Development of Self-Esteem. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(5), 381–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414547414

Perloff, R. M. (2014). Social Media Effects on Young Women’s Body Image Concerns: Theoretical Perspectives and an Agenda for Research. Sex Roles, 71(11), 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0384-6

R Core Team. (2023). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (version 4.3.2) [Software]. https://www.R-project.org

Raich, R. M., Mora, M., Soler, A., Avila, C., Clos, I., & Zapater, L. (1996). Adaptación de un instrumento de evaluación de la insatisfacción corporal. [Adaptation of a body dissatisfaction assessment instrument.]. Clínica y Salud, 7(1), 51–66. https://journals.copmadrid.org/clysa/art/f2217062e9a397a1dca429e7d70bc6ca

Ribeiro Cardoso, P., Jólluskin, G., Paz, L., Fonseca, M. J., & Silva, I. (2023). Effects of awareness campaigns against domestic violence: Perceived efficacy, adopted behavior and word of mouth. Journal of Criminological Research, Policy and Practice, 9(3/4), 177–192. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCRPP-11-2022-0057

Richards, J. I., & Curran, C. M. (2002). Oracles on “Advertising”: Searching for a Definition. Journal of Advertising, 31(2), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2002.10673667

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt183pjjh

Rozin, P., & Royzman, E. B. (2001). Negativity Bias, Negativity Dominance, and Contagion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5(4), 296–320. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0504_2

Soti, R. (2022). The impact of advertising on consumer behavior. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 14(3), 706–711. https://doi.org/10.30574/wjarr.2022.14.3.0577

Selensky, J. C., & Carels, R. A. (2021). Weight stigma and media: An examination of the effect of advertising campaigns on weight bias, internalized weight bias, self-esteem, body image, and affect. Body Image, 36, 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.10.008

Servicio Nacional del Consumidor. (2024). Informe Anual de Publicidad Sexista 2024. https://www.sernac.cl/portal/619/w3-article-84761.html

Smith, O. E., Mills, J. S., & Samson, L. (2024). Out of the loop: Taking a one-week break from social media leads to better self-esteem and body image among young women. Body Image, 49, 101715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2024.101715

Terry, W. S. (2005). Serial Position Effects in Recall of Television Commercials. The Journal of General Psychology, 132(2), 151–164. https://doi.org/10.3200/GENP.132.2.151-164

Thornborrow, T., Boothroyd, L. G., & Tovee, M. J. (2025). “Thank God we are like this here’’: A qualitative investigation of televisual media influence on women’s body image in an ethnically diverse rural Nicaraguan population. Body Image, 52, 101817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2024.101817

Vandenbosch, L., Fardouly, J., & Tiggemann, M. (2022). Social media and body image: Recent trends and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, 101289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.12.002

Villalobos, H. P. (2019). Autoestima, teorías y su relación con el éxito personal. Alternativas en Psicología, 41, 22–31. https://alternativas.me/autoestima-teorias-y-su-relacion-con-el-exito-personal/

Statements

Author Contributions: Raquel Corales: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, and Writing – original draft. Millaray Correa: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, and Writing – original draft. José Luis Ulloa: Supervision, Conceptualization, Project administration, Formal analysis, Visualization, Resources, and Writing – review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study received no external funding.

Acknowledgments: We acknowledge the support of the Centro de Investigación en Ciencias Cognitivas (CICC) for administrative and technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics Committee Review Statement: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology at the University of Talca, act code: “Certificacion_Etica_2023_06_20”, date of approval: June 20, 2023.

Informed Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Artificial Intelligence Statement: During preparation of this work, the authors made use of GPT-3.5, developed by OpenAI (https://www.openai.com), in order to improve language and readability. The authors have thoroughly reviewed and revised the output and accept full responsibility for the content of this publication.