|

|

Ibero-American

Journal of Psychology and Public Policy |

Research Article |

Myths about Health and Abortion Scale (MHAS): design and psychometric properties in a Chilean community population

(Escala de Mitos sobre Salud y Aborto [EMSA]: diseño y propiedades psicométricas en población comunitaria chilena)

Beatriz Pérez 1,* and Carolina Alveal-Álamos 2

1 Departamento de Psicología, Universidad de Oviedo, Spain;

perezbeatriz@uniovi.es ![]()

Departamento de Psicología, Universidad de La Frontera, Chile; beatriz.perez@ufrontera.cl

2 Magíster

en Estudios Interculturales, Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile; calveal@uct.cl

![]()

* Correspondence: perezbeatriz@uniovi.es

|

Reference: Pérez, B., & Alveal-Álamos, C. (2024). Myths about Health and Abortion Scale (MHAS): design and psychometric properties in a Chilean community population (Escala de Mitos sobre Salud y Aborto [EMSA]: diseño y propiedades psicométricas en población comunitaria chilena). Ibero-American Journal of Psychology and Public Policy, 1(2), 175-202. https://doi.org/10.56754/2810-6598.2024.0015 Editor: Leticia de la Fuente Reception date: 22 Jan 2024 Acceptance date: 08 Jun 2024 Publication date: 29 Jul 2024 Language: English and Spanish Translation: Helen Lowry Publisher’s Note: IJP&PP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Copyright: © 2024 by the authors. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY NC SA) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/). |

Abstract: Myths about health and abortion in Chile have been identified as a barrier to the implementation of Law 21.030 on the Voluntary Termination of Pregnancy. However, no measure adapted to the Chilean socio-cultural reality with adequate psychometric properties would allow us to verify the extent of misinformation. This study aims to design and analyze the psychometric properties of the Myths About Health and Abortion Scale (MHAS) in a Chilean community population. This study presents a sample of 613 participants. We obtained a unidimensional 5-item scale by cross-validity (χ2 = 21.702; df = 4; p < .001); RMSEA = .085 (90% CI [.052, .122]); CFI = .993; TLI = .982; GFI = .995) with adequate reliability of scores in the study sample (Sub-sample 1, McDonald's omega = .871; Sub-sample 2, McDonald's omega = .842); and evidence of validity in relation to other variables (e.g., the MHAS correlates with Sexual Double Standard (r = .354; p < .001), and Group Dominance (r = .307; p < .001), for use on the Chilean population. The most uninformed participants have a low education level, are older, have a conservative ideological profile in terms of religion and politics, and have a higher agreement with sexual double standards and social domination. This new approach allows us to quantify the issue of stigmatization and decision-making faced by women contemplating abortion, as well as to expose the deliberate dissemination of misinformation as a political strategy to oppose permissive abortion legislation. Keywords: beliefs; voluntary termination of pregnancy; instrument; validity; reliability; misinformation. Resumen: Los mitos sobre salud y aborto en Chile han sido identificados como una barrera para la implementación de la Ley 21.030 sobre Interrupción Voluntaria del Embarazo. No obstante, no existe una medida adaptada a la realidad sociocultural chilena con adecuadas propiedades psicométricas que nos permita constatar la extensión de la desinformación. Este estudio tiene como objetivo diseñar y analizar las propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Mitos sobre Salud y Aborto (EMSA) en población comunitaria chilena. Este estudio presenta una muestra de 613 participantes. Como resultado obtuvimos una escala de 5 ítems unidimensional mediante validez cruzada (χ2 = 21,702; gl = 4; p < ,001; RMSEA = ,085 (IC 90% [,052 ,122]); CFI = ,993; TLI = ,982; GFI = ,995); con adecuada fiabilidad de las puntuaciones en la muestra de estudio (submuestra 1, Omega de McDonald = ,871; submuestra 2, Omega de McDonald = ,842); y evidencias de validez en relación con otras variables (p. ej., , EMSA correlaciona con Doble Moral Sexual (r = ,354; p < ,001), y Dominación Grupal (r = ,307; p < ,001) para su uso con población chilena. Las y los participantes más desinformados tienen un bajo nivel educativo, son mayores, un perfil ideológico conservador en lo religioso y lo político, y mayor acuerdo con el doble estándar sexual y la dominación social. Esta nueva herramienta nos brinda la posibilidad de medir una problemática implicada en la estigmatización y toma de decisión de las mujeres que se plantean el acceso al aborto; y de transparentar el uso de la desinformación como estrategia política para desincentivar políticas permisivas sobre el aborto. Palabras clave: creencias; interrupción voluntaria del embarazo; instrumento; validez; fiabilidad; desinformación. Resumo: Os mitos sobre saúde e aborto no Chile foram identificados como uma barreira à implementação da Lei 21.030 sobre a Interrupção Voluntária da Gravidez. No entanto, não existe uma medida adaptada à realidade sociocultural chilena com propriedades psicométricas adequadas que nos permita verificar a extensão da desinformação. Este estudo tem como objetivo desenhar e analisar as propriedades psicométricas da Escala de Mitos sobre Saúde e Aborto (EMSA) numa população comunitária chilena. Este estudo apresenta uma amostra de 613 participantes. Como resultado, obtivemos uma escala unidimensional de 5 itens, por validade cruzada (χ2 = 21,702; gl = 4; p < ,001; RMSEA = ,085 (IC 90% [,052 ,122]); CFI = ,993; TLI = ,982; GFI = 995); com fiabilidade adequada das pontuações na amostra do estudo (Subamostra 1, Omega de McDonald = ,871; Subamostra, Omega de McDonald = ,842); e evidência de validade em relação a outras variáveis (por exemplo, o EMSA correlaciona-se com a Moral Sexual Dupla (r = ,354; p < ,001), e a Dominância de Grupo (r = ,307; p < ,001), para uso com a população chilena. Os participantes mais desinformados têm um baixo nível de escolaridade, são mais velhos, têm um perfil ideológico conservador na religião e na política, e têm uma maior concordância com a dupla moral sexual e a dominação social. Esta nova ferramenta dános a possibilidade de medir um problema implicado na estigmatização e na tomada de decisão das mulheres que consideram aceder ao aborto; e de tornar transparente a utilização da desinformação como estratégia política para desencorajar políticas permissivas sobre o aborto. Palavras-chave: crenças; interrupção voluntária da gravidez; instrumento; validade; confiabilidade; desinformação.

|

1. Introduction

Chile, a country with a strong conservative identity that has had a significant impact on the formulation of social policies, was notably distinguished for banning abortion under any circumstances. However, Law 21.030 (2017) allowed legal and safe abortion in cases of danger to the woman's life, fetal non-viability, and rape (Maira et al., 2019; Muñoz et al., 2021). Despite this progress, social monitors of the Law reveal significant obstacles to its implementation, such as conscientious objection, lack of information about the Law, abortion, and abortion procedures among health professionals and the community, as well as prejudices and myths about abortion (Alveal-Álamos et al., 2022; Casas et al., 2022; Mesa Acción por el Aborto en Chile [MAACH], 2023; Montero et al., 2022).

Myths surrounding abortion linked to health risks are common. On a physical level, abortion has been identified as a dangerous intervention. In reality, serious complications of abortion are rare when performed legally (Faundes, 2015). Death is more likely during childbirth than during an abortion (Stevenson, 2021). In the long term, abortion has been linked to breast cancer and infertility (Patev & Hood, 2021). Although meta-analyses support the link between breast cancer and abortion (Islam et al., 2022), others disprove them and claim methodological errors (Tong et al., 2020). The National Cancer Institute in the U.S. denies this relation (Pagoto et al., 2023). The link between abortion and infertility has also been disproven (Johnson et al., 2021). For their part, Ralph et al. (2019) suggest that the health of women who have had abortions is no worse than those who have carried pregnancies to term after being unable to access abortion. Indeed, some differences indicate worse health in the group that gave birth.

Abortion myths extend to the emotional realm (Patev & Hood, 2021), associating abortion with diagnostic categories such as "Postabortion Depression and Psychosis" or "Postabortion Trauma", discredited by the American Medical Association and not recognized in the DSM-5 or ICD-11. The controversy persists with support from some in the scientific community (Jacob et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2018) and refutation by others who point out methodological errors and pre-existing risk factors. These may include circumstances of unwanted pregnancy, political barriers to access, abortion stigma, and personal variables such as low resilience, low social support, relationship dissatisfaction, intimate partner violence, pre-existing mental health issues, and pro-life attitudes (Reardon, 2018; Rajkumar, 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). There is also literature indicating innocuous effects or improvements in postabortion mental health. For example, Holmlund et al. (2021) conclude that abortion history does not affect the early self-efficacy and psychological well-being of parents.

Despite this, misinformation about the physical and emotional effects of abortion is common (Berglas et al., 2017; Patev & Hood, 2021; Swartz et al., 2020) not only among individuals but also in the information provided to the community by governmental institutions (Berglas et al., 2017). Osorio-Rauld (2013) examines Chilean legislators' use of science and pseudo-science in their speeches, particularly when those speeches have ideological or moral undertones. Even Pagoto et al. (2023) assert that we are on the verge of an abortion infodemic fueled by a confusing and changing legislative landscape. In this context, abortion myths are used as a political and propaganda tool by polarized groups against this practice, a persuasion strategy to prevent the proliferation of the practice and decriminalization laws (Swartz et al., 2020). These groups tend to identify with conservative religious and political values, variables with greater weight when explaining negative attitudes towards abortion (Alveal-Álamos et al., 2022; Camacho, 2019; Pérez, Burgos, et al., 2022; Pérez, Concha-Salgado, et al., 2022), and with traditional gender attitudes and an orientation to social dominance (Cárdenas, Lay, et al., 2010; Cárdenas, Meza, et al., 2010; Cárdenas et al., 2022; Pérez, Concha-Salgado, et al., 2022).

The paucity of evidence supporting the extent of abortion misinformation is addressed in Patev and Hood's (2021) systematic review that examined nine studies in the United States. The research validates the widespread existence of misconceptions about abortion and emphasizes that a substantial portion of the population harbors skepticism over their veracity. Few studies have investigated the characteristics associated with misinformation. Littman et al. (2014), in a sample of women who had an abortion, found that older women and women with children were less likely to support the infertility myth, whereas black and less educated women were less likely to support the depression myth. Berglas et al. (2017), in a sample of women who sought abortion information, find that young, non-white women and those with no past abortion experience are more supportive of abortion myths. Kavanaugh et al. (2013), in a community sample, reported that those with less knowledge about abortion have lower education levels, less understanding of sexual and reproductive health, and less support for the legality of abortion, with no differences in knowledge between men and women. Swartz et al. (2020) report greater misinformation among women who disapprove of legal abortion.

In Chile and other regions of Latin America, we found no information to help us understand the extent and scope of abortion myths and misinformation. Given the ongoing legislative debate on abortion in Chile and the deliberate use of false information as a political strategy (Osorio-Rauld, 2013; Palma & Moreno, 2015; Swartz et al., 2020), it is crucial to develop a concise and user-friendly tool that accurately measures beliefs in health and abortion myths adapted to the country's current sociocultural context. Furthermore, misinformation has consequences; for example, a lack of trust in public health recommendations, difficulties in decision-making and coping for women seeking abortion, and stigmatization from both the community and ill-informed healthcare professionals (Alveal-Álamos et al., 2022; Casas et al., 2022; Littman et al., 2014; MAACH, 2023 Montero et al., 2022; Pagoto et al., 2023). To address this issue, some of the papers reviewed have developed their own measures to assess knowledge about abortion myths. Berglas et al. (2017) asked participants to choose which of two statements came closest to the truth about five myths about abortion safety and long-term physical and psychological risks. They offered the possibility of a third response option: I don't know/am not sure. Swartz et al. (2020) asked five questions using the same method. Littman et al. (2014) queried about common myths using four Likert-type questions. Kavanaugh et al. (2013) included different types of abortion knowledge questions in the sexual and reproductive health knowledge questionnaire: multiple choice between four options on prevalence and probability, with only one option being correct; assessment of relative risk in different reproductive health situations; and expression of level of agreement using a Likert scale to assess knowledge about the consequences of different situations. However, no studies have been done on the psychometric properties of these measures. In addition, they have been developed according to the socio-cultural reality of the US. For this reason, we believe it is relevant to design a measure for the Chilean population in accordance with the myths about health and abortion that are widespread in the country. In a previous work, Pérez, Burgos, et al. (2022) collected information to formulate items about health and abortion myths to create the Voluntary Abortion Attitudes Scale (VAAS). For this purpose, in addition to reviewing the literature, they analyzed interviews used in a previous study with the Chilean community (Pérez et al., 2020) and social representations on abortion through a focus group with pro-choice activists and consulted with professionals/researchers in the area. The items about health myths and abortion fulfilled indicators of discriminative ability in the pilot study and the final sample with 118 and 1,223 participants, respectively. However, they were ultimately discarded because they presented low correlations with other items or because of theoretical criteria. These items are recovered in the present study for the MHAS design.

2. Objectives and hypotheses

In short, this study aims to design and analyze the psychometric properties of the Myths about Health and Abortion Scale (MHAS). Others derive from this objective:

(1) analyze the items descriptively;

(2) demonstrate evidence of validity based on internal structure;

(3) test the internal consistency coefficient of the scores as evidence of reliability;

(4) demonstrate evidence of validity based on the relationship with other variables: sociodemographic (education level, age, and gender), and ideological (religiosity, political orientation, sexual double standards, and social dominance).

Kavanaugh et al. (2013) found greater endorsement of myths among people with a low education level in the community sample. According to them, it is hypothesized that participants with a higher education level will obtain lower MHAS scores than participants with a lower education level (H1). In terms of age, in line with the work of Berglas et al. (2017) and Littman et al. (2014), greater support of the myths is expected among younger participants than among older people (H2). Furthermore, (H3) no differences in scores are expected according to gender (Kavanaugh et al., 2013). Furthermore, the influence of right-wing religious and political beliefs on the formation of an anti-VTP (voluntary termination of pregnancy) stance is significant (Alveal-Álamos et al., 2022; Camacho, 2019; Pérez, Burgos, et al., 2022; Pérez, Concha-Salgado, et al., 2022; Pérez et al., 2020). This is due to confirmation bias (Myers & Twenge, 2019), which can lead to the reinforcement of misconceptions about health and abortion to support negative preconceived notions about abortion. Anti-abortion groups also employ misinformation as a political strategy (Osorio-Rauld, 2013; Palma & Moreno, 2015; Swartz et al., 2020). Additionally, studies by Kavanaugh et al. (2013) and Swartz et al. (2020) have found that individuals who support the illegalization of abortion are more likely to endorse misinformation. Participants who have higher scores on the Universal Religious Involvement Scale (H4) and identify as right-wing politically (H5) are expected to have higher scores on the MHAS compared to those who have low scores on both scales. Finally, it is expected that the scores obtained in the MHAS will correlate significantly and positively with the scores obtained on the Sexual Double Standard Scale (H6) and with the Social Dominance factor on the Social Dominance Orientation Scale (H8) and negatively with the Opposition to Equality factor (H7). This is because the literature relates a conservative religious and political ideological profile with traditional attitudes about gender and social dominance (Cárdenas, Lay, et al., 2010; Cárdenas, Meza, et al., 2010; Cárdenas et al., 2022; Pérez, Concha-Salgado, et al., 2022).

3. Method

3.1. Participants

The sample consisted of 613 participants. Convenience and quota sampling were used: (a) geographic macro-zone (15.8% in the northern zone, 58.2% in the central zone, and 25.9% in the southern zone) according to the distribution of population density in the country; (b) sex (51.4% men and 48.6% women); (c) age (50.6% between 18 and 30 years old, and 49.4% from 31 years and older); and (d) socioeconomic group (SEG), based on the classification system of the Association of Market Researchers (33.3% to high SEG; 32.8% to medium SEG; and 33.9% to low SEG). The mean age was 37.14 years (SD = 15.30). Table 1 shows the descriptive data of the total sample and subsamples 1 and 2.

Table 1

Descriptive data of the complete sample and by subsamples

|

Variables |

Categories |

Total Sample (N = 613) |

Subsample 1 (n = 306; 49.9%) |

Subsample 2 (n = 307; 50.1%) |

|||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

||

|

Gender |

Female |

298 |

48.6 |

164 |

53.6 |

151 |

49.2 |

|

Male |

315 |

51.4 |

142 |

46.4 |

156 |

50.8 |

|

|

Age |

Between 18 and 30 years |

310 |

50.6 |

160 |

52.3 |

150 |

48.9 |

|

31 years and older |

303 |

49.4 |

146 |

47.7 |

157 |

51.1 |

|

|

Area of country where resident |

North |

97 |

15.8 |

58 |

19 |

39 |

12.7 |

|

Center |

357 |

58.2 |

175 |

57.2 |

182 |

59.3 |

|

|

South |

159 |

25.9 |

73 |

23.9 |

86 |

28 |

|

|

Socioeconomic Group

|

AB (High) |

20 |

3.3 |

11 |

3.6 |

9 |

2.9 |

|

C1a (Upper middle) |

69 |

11.3 |

35 |

11.4 |

34 |

11.1 |

|

|

C1b (Emerging middle) |

115 |

18.8 |

59 |

19.3 |

56 |

18.2 |

|

|

C2 (Middle middle) |

92 |

15.0 |

52 |

17 |

40 |

13 |

|

|

C3 (Lower middle) |

109 |

17.8 |

56 |

18.3 |

53 |

17.3 |

|

|

D (Vulnerable) |

130 |

21.2 |

54 |

17.6 |

76 |

24.8 |

|

|

E (Poor) |

78 |

12.7 |

39 |

12.7 |

39 |

12.7 |

|

|

Education level (studies) |

High school or less |

165 |

26.9 |

83 |

27.1 |

82 |

26.7 |

|

Incomplete technical or university |

217 |

35.4 |

105 |

34.3 |

112 |

36.5 |

|

|

University or postgraduate |

231 |

37.7 |

118 |

38.6 |

113 |

36.8 |

|

|

Marital status |

Single |

329 |

53.7 |

167 |

54.6 |

162 |

52.8 |

|

Married |

138 |

22.5 |

69 |

22.5 |

69 |

22.5 |

|

|

Co-habiting |

103 |

16.8 |

53 |

17.3 |

50 |

16.3 |

|

|

Separated, Divorced |

37 |

6.0 |

15 |

4.9 |

22 |

7.2 |

|

|

Widowed |

6 |

1 |

2 |

0.7 |

4 |

1.3 |

|

|

Indigenous people |

No |

510 |

83.2 |

252 |

82.4 |

258 |

84 |

|

Mapuche |

78 |

12.7 |

40 |

13.1 |

38 |

12.4 |

|

|

Other |

25 |

4.1 |

14 |

4.6 |

11 |

3.6 |

|

|

Political leaning |

Left |

140 |

22.8 |

74 |

24.2 |

66 |

21.5 |

|

Neither left nor right |

403 |

65.7 |

189 |

61.8 |

214 |

69.7 |

|

|

Right |

70 |

11.4 |

43 |

14.1 |

27 |

8.8 |

|

3.2. Design

This study is based on an instrumental design (Ato et al., 2013). It considers the recommendations of Lloret-Segura et al. (2014) for selecting methodology based on evidence of validity and reliability and statistical analyses to prove them.

3.3. Instruments

3.3.1. Ad hoc sociodemographic questionnaire.

It includes aspects such as gender, age, ethnic identification, rural or urban origin, education level, or political leaning.

3.3.2. Myths about Health and Abortion Scale (MHAS)

The MHAS (see Appendix 1) assesses the level of agreement with myths/misconceptions about physical and mental health and abortion. The response scale is a five-point Likert-type scale, where 1 means strongly disagree, and 5 means strongly agree. The higher the score, the higher the erroneous beliefs about health and abortion. For more information on the design phases, see the work by Pérez, Burgos, et al. (2022).

3.3.3. Universal Religious Involvement Scale (I-E 12)

The I-E 12 adapted for Chilean schoolchildren by Flores Jara et al. (2019) measures religious involvement across three dimensions: Intrinsic Orientation (IO) consists of six items, salience of the religious social category versus others for the configuration of the self-concept; Extrinsic Social Orientation (ESO) consists of three items, social gain at the level of status and personal interaction; and Extrinsic Personal Orientation (EPO) consists of three items, personal gain at the level of protection and comfort. The Likert-type response scale has five options, where 1 means strongly disagree, and 5 means strongly agree. The higher the score, the greater the presence of the dimension in the participant. This structure was adjusted in a Chilean community sample (Pérez, Burgos, et al., 2022; Pérez, Concha-Salgado, et al., 2022). In this study, the three dimensions present an adequate estimate of the reliability of the scores (IO, α = .924; ESO, α = .893; EPO, α = .864).

3.3.4. Sexual Double Standard Scale (DSS)

The DSS, adapted to the Chilean university population (Díaz-Gutiérrez et al., 2022), measures double sexual morality, i.e., the differentiated evaluation of the same sexual behaviors depending on the gender of the person who performs them. This Likert-type scale has five response options, where 1 means strongly disagree, and 5 means strongly agree, consists of 10 items, and is unidimensional. The higher the score, the greater the presence of the construct in the participant. In the present study, the estimate of the reliability of the scores was good, with a value of α = .890.

3.3.5. Social Dominance Orientation Scale (SDO)

The SDO adapted to the Chilean population by Cárdenas, Meza, et al. (2010) assesses the predisposition of individuals towards the maintenance of hierarchical and non-egalitarian intergroup relations. This scale has two dimensions in its Chilean version, with eight items each: Group Dominance (GD), meaning the desire to maintain dominance and hierarchies, and Opposition to Equality (OE), the resistance to equal treatment of individuals. The SDO is a 7-point Likert-type scale, where 1 means strongly disagree, and 7 means strongly agree. The higher the score, the greater the presence of both constructs. In the present study, the reliability estimate of the scores on both dimensions was good: GD, α = .853; OE, α = .906.

3.4. Procedure and ethical safeguards

After approval by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Universidad de La Frontera, the questionnaire was submitted to an online pilot study by convenience, with a sample of 67 community members obtained by snowball sampling. 70% (n = 47) were women, and the mean age was 36.16 years. Participants were asked to report confusing or difficult-to-understand aspects of instructions and items. No modifications to the instrument battery were needed. Subsequently, the study sample was obtained through Netquest, a company that provides market research data per ISO 26362:2009. This company has specialized panels of participants and records their sociodemographic variables. This makes the prior selection of participants possible based on quotas by sex, age, geographic area, and SEG. The online application lasted approximately 15 minutes.

3.5. Analysis strategy

Descriptive and frequency statistics were used to describe the sample and items. To analyze the discriminative capacity of the items, the skewness and kurtosis values of each item and the item-total correlation were calculated, assuming that higher levels of +/- 1 in skewness and kurtosis and lower levels of .3 in item-total correlation were indicators of low discriminative capacity. Multivariate normality was checked using Mardia's coefficient. In addition, the correlation matrix between the items was analyzed to corroborate the significant relationship among all the items and the absence of correlations that were too high (higher than .8) or too low (lower than .2), which could be indicative of redundant items or items that do not measure the same construct as the rest.

For the study of the factorial structure of the MHAS, a cross-validity procedure was used by randomly dividing the sample into 2 subsamples. With subsample 1, after checking the suitability of the sample size to perform an exploratory factor analysis (EFA), i.e., a minimum size of 200 participants when the communalities are between .40 and .70, with a minimum of 3 or 4 items per factor, and the quality of the correlation matrix using Bartlett's index and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test, we proceeded to carry out an EFA considering unweighted least squares and direct oblimin rotation as the extraction process. In addition, the unidimensional congruence (UniCo) value, the explained common variance (ECV) value, and the media of residual absolute item loadings (MIREAL) were reviewed to determine whether the scale can be considered essentially unidimensional (UniCo > .95; ECV > .85; MIREAL < .30; Ferrando and Lorenzo-Seva, 2018).

Subsequently, the resulting structure was replicated in subsample 2 using a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Since the data were ordinal, the robust unweighted least squares estimator (ULSMV) was considered in a polychoric matrix. The fit of the structure was evaluated with the absolute fit indices, root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), and global goodness-of-fit index (GFI), and with the incremental fit indices, the comparative fit index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). CFI, TLI, and GFI ≥ .95 and RMSEA < .05 were considered to indicate a good fit; and a CFI, TLI, and GFI ≥ .90 and RMSEA < .08 an acceptable fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1999). In addition, the convergent validity of the items was analyzed through the average variance extracted (AVE). The AVE is acceptable from .50 since the construct must share more than half the variance with its items (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Once the factorial structure was confirmed, the internal consistency of the resulting unidimensional structure was analyzed using Cronbach's standardized alpha and McDonald's omega, indicated in the case of polychoric matrices (Elosua & Zumbo, 2008). A good internal consistency was considered from .70 for the three coefficients (George & Mayer, 2018).

The validity evidence concerning other constructs and variables was analyzed using Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) and Student's t-test for the difference of means with Welch's correction when group sizes and/or variances were unequal. Comparison groups were formed based on scores on sociodemographic and ideological variables. For gender, MHAS scores were compared between men and women. In the case of political leaning, those who identified with the left were compared to those who identified with the right. For the remaining variables, the extreme groups comparison strategy was used. This involves selecting participants with extreme scores, i.e., those who fall into quartiles 1 and 4 on each variable. Finally, the effect size was evaluated using Cohen's d (Cohen, 1998) and its confidence level (Hedges & Olkin, 1985): small effect when d > 0.2, intermediate when d > 0.5, and large when d > 0.8. The statistics packages SPSS 24 for Windows, Mplus 7, Factor 10.9, and JASP 18.03 were used.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive analysis of the items

Table 2 shows the descriptive analyses of the items in the whole sample (N = 613). All values show adequate skewness and kurtosis values. Despite this, the multivariate normality assumption is not fulfilled (skewness: Mardia’s coefficient = 1.594, χ2 = 162.859, df = 35, p < .001; kurtosis: Mardia’s coefficient = 42.608, z = 11.256, p < .001). Nevertheless, the values of the discrimination index of the items (corrected item-total correlation) are higher than .3 in every case, and no item reaches a frequency of 95% in any response option (the maximum response frequencies range between 35.1% and 43.2%), a symptom that the items are informative and can differentiate between participants. In addition, the correlation matrix yields statistically significant values in every case, with values ranging from .366 to .662, and eliminating items could affect the evidence of content validity. Consequently, none of the items were eliminated.

4.2. Evidence of validity based on internal structure.

In subsample 1 (n = 306), the communalities are greater than .4 except for item 5. This is indicative of the adequacy of the sample size. The KMO index is equal to .840, and Bartlett's test of sphericity is statistically significant: χ2(10) = 589.4, p < ,001. Both data indicate that the correlation matrix is suitable for an EFA. As a result, a unifactorial structure was obtained that explains 65.7% of the variance, with factor weights ranging from .588 to .716. In addition, UniCo = .994, ECV = .926, and MIREAL = .199 indicate that the data can be treated as essentially unidimensional.

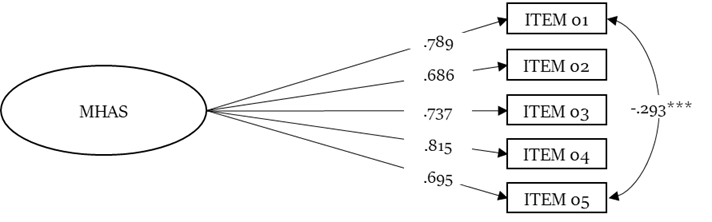

The unidimensional structure was subjected to a CFA in subsample 2 (n = 307). An adequate fit was obtained: χ2 = 21.702; df = 4; p < .001; RMSEA = .085 (90% CI [.052, .122]); CFI = .993; TLI = .982; GFI = .995, after correlating errors for items MHAS01 (A woman carries the trauma of abortion all her life) and MHAS05 (Women who abort with medication often have risks in their future pregnancies). Figure 1 shows the factor weights of the scale items. The AVE was .518.

Table 2

Descriptive statistics, discrimination index for the complete sample, and EFA statistics and reliability in both subsamples

|

|

|

Complete sample |

|

SS 1 |

|

SS 2 |

|||||||

|

N |

Items |

|

M |

SD |

Skew. |

Kurt. |

Corrected ITC |

|

h2 |

λ EFA |

Ω if eliminated |

Ω if eliminated |

|

|

1 |

A woman carries the trauma of abortion all her life. |

|

3.15 |

1.118 |

-.284 |

-.517 |

.634 |

|

.472 |

.764 |

.816 |

.777 |

|

|

2 |

To avoid trauma, a girl should consider other alternatives to abortion. |

|

2.88 |

1.145 |

-.110 |

-.766 |

.603 |

|

.430 |

.745 |

.816 |

.801 |

|

|

3 |

The health of a woman who has an abortion is never as good as it was before the abortion. |

|

2.41 |

1.067 |

.184 |

-.742 |

.632 |

|

.439 |

.766 |

.814 |

.785 |

|

|

4 |

Abortion often leads to depression in the women who undergo it. |

|

2.94 |

1.056 |

-.357 |

-.413 |

.710 |

|

.584 |

.887 |

.786 |

.765 |

|

|

5 |

Women who have medical abortions often have risks in future pregnancies. |

|

3.02 |

1.021 |

-.369 |

-.100 |

.565 |

|

.311 |

.614 |

.838 |

.789 |

|

Note: SS 1 = Subsample 1; SS 2 = Subsample 2; M = Mean; SD = Standard Deviation; Skew. = Skewness; Kurt. = Kurtosis; Corrected ITC = Corrected item-total correlation (discrimination index); h2 = Communality; λ EFA = Factor loading of the item in the exploratory factor analysis; Ω if eliminated = McDonald's Omega if the item is eliminated.

Figure 1

Factor weights of the MHAS items in the unidimensional structure, including the error covariance between items 1 and 5

Note: *** = p < .001.

4.3. Internal consistency coefficients of the scores as evidence of reliability.

The internal consistency coefficients of the single-factor structure of the MHAS are acceptable in both subsample 1, standardized Cronbach's alpha = .842 (95% CI [.812, .868]), McDonald's omega = .846 (95% CI [.819, .873]); and subsample 2, standardized Cronbach's alpha = .818 (95% CI [.783, .848]), McDonald's omega = .818 (95% CI [.786, .851]). As Table 1 illustrates, McDonald's omega does not improve substantially by eliminating any item.

4.4. Validity based on the relationship with other variables

Statistically significant differences were found between groups based on age and education level with a small effect size, based on social extrinsic religious orientation with an intermediate effect size, and based on intrinsic religious orientation, personal extrinsic orientation, and political leaning with a large effect size. No statistically significant differences were found concerning the participants’ gender. Consequently, older participants with a lower education level, a right-wing or very right-wing political leaning, and a high intrinsic and extrinsic personal and social religious orientation have higher scores on the MHAS (see Table 3).

Table 3

Comparison of mean MHAS scores between groups based on sociodemographic and ideological variables

|

|

Group/Quartile |

n |

Min. |

Max. |

Mean |

SD |

T/Welch |

df |

p |

d |

d [95% CI] |

|

Education level |

|

||||||||||

|

|

High school or less (Q1) |

165 |

5 |

24 |

15.121 |

3.893 |

3.885* |

374.459 |

<.001 |

0.39 |

[0.19, 0.59] |

|

|

University or more (Q4) |

231 |

5 |

25 |

13.502 |

4.347 |

|||||

|

Age |

|||||||||||

|

|

18- 26 (Q1) |

170 |

5 |

23 |

13.617 |

4.350 |

-4.038 |

324.424 |

<.001 |

0.44 |

[0.22, 0.66] |

|

|

47-79 (Q4) |

161 |

5 |

24 |

15.397 |

3.654 |

|||||

|

Gender |

|||||||||||

|

|

Men |

298 |

5 |

25 |

14.668 |

4.180 |

-1.501 |

608.848 |

.134 |

0.12 |

[0.28, 0.37] |

|

|

Women |

315 |

5 |

25 |

14.162 |

4.162 |

|||||

|

Political leaning |

|

||||||||||

|

|

Left or very left |

140 |

5 |

24 |

12.064 |

4.085 |

-7.668* |

152.151 |

<.001 |

1.09 |

[0.78, 1.39] |

|

|

Right or very right |

70 |

5 |

25 |

16.342 |

3.666 |

|||||

|

Intrinsic Religious Orientation |

|

||||||||||

|

|

Low (Q1) |

155 |

5 |

24 |

12.458 |

4.473 |

8.185 |

300.452 |

<.001 |

0.93 |

[0.69, 1.16] |

|

|

High (Q4) |

158 |

5 |

25 |

16.291 |

3.774 |

|||||

|

Social Extrinsic Religious Orientation |

|

||||||||||

|

|

Low (Q1) |

318 |

5 |

25 |

13.358 |

4.285 |

-7.697* |

383.320 |

<.001 |

0.69 |

[0.49, 0.88] |

|

|

High (Q4) |

154 |

5 |

25 |

16.175 |

3.362 |

|||||

|

Personal Extrinsic Religious Orientation |

|

||||||||||

|

|

Low (Q1) |

160 |

5 |

24 |

12.543 |

4.494 |

-7.541 |

321 |

<.001 |

0.84 |

[0.61, 1.07] |

|

|

High (Q4) |

163 |

5 |

25 |

16.012 |

3.744 |

|||||

Note: M = Mean; SD = Standard Deviation; * = statistic with Welch's correction.

Finally, as evidence of validity in relation to other variables, we found that the MHAS correlates statistically significantly and positively with the DSS scale, r = .354, p < .001, 95% CI [.283, .421] and with the factor of GD on the SDO, r = .307, p < .001, 95% CI [.233, .377]. We did not find a statistically significant relationship between MHAS and the factor of OE on the SDO, r = .056, p = .169, 95% CI [-.134, .024].

5. Discussion

Given the implications of misinformation and the propagation of myths about abortion, the present study aimed to develop the MHAS and analyze its psychometric properties, a measure to assess agreement with erroneous and mythical beliefs about physical and mental health in abortion, according to Chile’s sociocultural reality.

Formulating the items on the MHAS results from an extensive process involving several study phases with the Chilean population (Pérez, Burgos, et al., 2022). Consequently, items that were close in content to what other studies have typically measured were obtained. This is the case of item 1, "A woman carries the trauma of abortion all her life," which picks up on the widespread myth about the existence of "Postabortion Trauma," or item 4, "Abortion often leads to depression in women who undergo it," which alludes to the disproven relationship between depression and abortion (Berglas et al., 2017; Littman et al., 2014; Reardon, 2018; Rajkumar, 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). This is also the case for item 3, "The health of a woman who has an abortion is never as good as it was before the abortion." This item alludes to the relationship between the practice of abortion and a generalized worsening of health, disproven both mentally and physically (Faundes, 2015; Islam et al., 2022; Ralph et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2022).

However, other items were also obtained that represent myths about abortion tinged by the particularities of the Chilean situation. Item 2 "To avoid trauma, a girl should consider other alternatives to abortion" presumes that a minor's experience of a pregnancy carried to term and the search for other options -such as adoption- is less traumatic than the abortion itself. This belief may respond to the legislative controversy on abortion for minors under 14 years of age and the establishment of accompanying mechanisms that should not be used to influence the decision to have an abortion (Etcheberry, 2018). In this regard, Palma and Moreno (2015) analyzed speeches of political figures opposed to the decriminalization of abortion during the debate on Law 21.030 in Chile. Highlighted are speeches emphasizing society's responsibility in providing alternatives for women and girls considering abortion, viewing the decision as a consequence of isolation and limited opportunities. To this is added item 5, "Women who have medical abortions often have risks in their future pregnancies". This item alludes to a myth that has been picked up in Chilean press releases, identifying abortion pills as highly risky for health (Espinoza, July 25, 2018). In any case, and according to what was stated in specific objective 1, all the items showed discriminative ability in the study sample.

On the other hand, item 1 shows the highest mean score, and item 3 the lowest. Participants show a higher level of agreement with the statement regarding mental health (item 1) than the statement concerning physical health (item 3). This is consistent with the literature pointing to a greater spread of misinformation about mental health aspects (Berglas et al., 2017; Littman et al., 2014). However, in response to specific objectives 2 and 3, the examination of the validity evidence based on the internal structure of the scale yielded a unidimensional structure, and the internal consistency coefficients of the scores were adequate. These findings indicate that misinformation about physical and mental aspects in the study sample is articulated jointly, and different levels of misinformation are not distinguished depending on whether the myths allude to one or the other issue. This result coincides with measures developed by other authors (Berglas et al., 2017; Kavanaugh et al., 2013; Littman et al., 2014; Swartz et al., 2020). Therefore, there was evidence of validity based on internal structure as well as evidence of reliability.

The fourth specific objective was to demonstrate evidence of validity in relation to other variables. The results corroborate most of the hypotheses raised from this objective. However, some exceptions should be analyzed. First, according to the results of Kavanaugh et al. (2013), although in disagreement with the results of Littman et al. (2014), participants with a lower education level score higher on the scale. In other words, they are more uninformed. This result was expected since the MHAS is a measure of knowledge, and it is to be expected that people with lower education levels would have less knowledge on this or any other topic. Second, and contrary to what was expected according to what was reported by Littman et al. (2014), Berglas et al. (2017), and Kavanaugh et al. (2013), older participants support abortion myths to a greater extent. The explanation for this, contrary to the existing evidence, can be found in the socio-historical reality of the study sample. As mentioned at the beginning of this paper, Chile is a country with a conservative identity tradition strongly influenced by a recent dictatorship. The Baby Boomers and Generation X may have experienced limitations in accessing information about sexual and reproductive health issues, which subsequent generations have not (Maira et al., 2019). Finally, concerning sociodemographic variables, as we hypothesized, we found no differences based on gender. This finding demonstrates that misinformation is distributed evenly across both men and women, even though women are the primary group affected, a result already observed by Kavanaugh et al. (2013) in a community sample. In short, the results corroborate hypotheses H1 and H3 and disprove hypothesis H2.

Regarding the ideological variables, the results of this study corroborate hypotheses H4 and H5. Participants who identify with a right-wing political leaning and get higher scores on the religiosity scale factors (IO, EPO, and ESO) support myths to a greater extent than those who get lower scores and are left-leaning. This outcome is logical given the contrasting correlation between these variables, conservative values, and the disparity in abortion regulations. Kavanaugh et al. (2013) showed in a US sample that those who were less in agreement with abortion policies were Catholic, identified as politically conservative, and presented a greater lack of health knowledge on abortion issues. In addition, Swartz et al. (2020) also found greater misinformation among those who supported the illegality of abortion. Camacho et al. (2019) analyzed the political speeches of Chilean deputies. The parliamentarians belonging to right-wing parties confirmed their adherence to conservative ideological stances on abortion issues. Pérez, Burgos, et al. (2022) and Pérez, Concha-Salgado, et al. (2022) revealed that those with religious and right-wing political leanings in a Chilean community sample were found to support negative attitudes to abortion. These were based on conservative values.

Finally, the results corroborate hypotheses H6 and H8 but not hypothesis H7. The most uninformed participants also obtained high scores in sexual double standards, a construct that refers to the agreement with gender roles applied to sexual behaviors, i.e., they assess the same sexual behaviors differently depending on the gender of the person who performs them. This result supports studies that determine a relationship between gender attitudes and negative attitudes to abortion supported by ideologically conservative groups (Cárdenas, Meza, et al., 2010; Díaz-Gutiérrez et al., 2022; Pérez, Concha-Salgado, et al., 2022). On the other hand, uninformed participants also showed high scores in Social Dominance, a construct shown to be high among Chileans who identify with a right-wing political leaning and present traditional gender attitudes (Cárdenas, Lay, et al., 2010; Cárdenas, Meza et al., 2010; Cárdenas et al., 2022). We found no statistically significant relationship between the MHAS and the factor Opposition to Equality, which runs counter to expectations. Thus, misinformation on health and abortion is revealed as an expression of a conservative ideological profile, also manifested through positive attitudes towards gender-stereotyped sexual behaviors and a hierarchical view of social groups. These results provide evidence of validity in relation to other variables so that specific objective 4 can be considered fulfilled.

After confirming the satisfactory psychometric features of the MHAS in the study sample, it is worth noting that this scale has both limitations and strengths compared to other measures. Kavanaugh et al. (2013), in addition to Likert-scale questions similar to the MHAS items, include two more types of questions to inquire about prevalence, probability, and relative risk. Consequently, the Kavanaugh et al. (2013) measure is more informative. Conversely, the measurements of Berglas et al. (2017) and Swartz et al. (2020) provide individuals with the option to deliberately disregard which answer is correct when presented with health information and abortion questions that have only two choices. The MHAS offers the response option "neither agree nor disagree" as an alternative. However, this response option is integrated into the scale on the level of agreement and does not differentiate those who prefer to abstain from answering. On the other hand, the psychometric analysis presented in this study determines that the MHAS items are observable variables of a latent variable. This makes it possible to measure the intensity of the presence of a certain trait (in this case, beliefs about health and abortion) and to differentiate individuals based on the score obtained. None of the above authors nor Littman et al. (2014) manage to obtain such a measure, which limits them to treating the items independently. We must add that the MHAS has been developed in a Chilean sociocultural framework, making it more relevant than others for use in this context.

This study has limitations. Although the sample is balanced based on sociodemographic variables, it does not represent the Chilean population. In addition, it may be biased due to the data collection method: participants have knowledge and use of the Internet and computers, are part of an online panel for answering questionnaires, and have been rewarded with points that give access to products. A further limitation is the lack of exploration of evidence supporting content-based validity. It is also necessary to further investigate the lack of correlation between the MHAS score and the Opposition to Equality, an unexpected result in this study, to acquire further evidence of validity in the community population and to examine its application in specific populations. In future studies, we hope to investigate content validity through expert judgment and evidence of validity in relation to criteria such as supportive behaviors on abortion policies and their functioning with polarized and organized groups regarding abortion.

6. Conclusions

The MHAS is a parsimonious scale with scores that present adequate psychometric properties for use with members of the Chilean adult community. It is the only existing international scale with such characteristics designed to measure and differentiate people through their level of misinformation about health and abortion.

Escala de Mitos sobre Salud y Aborto (EMSA): diseño y propiedades psicométricas en población chilena

1. Introducción

Chile, país arraigado en una tradición identitaria conservadora con fuerte influencia en la formulación de políticas sociales, destacaba por prohibir el aborto en toda circunstancia. Sin embargo, la Ley 21.030 (2017) permitió el aborto legal y seguro en casos de peligro para la vida de la mujer, inviabilidad fetal letal y violación (Maira et al., 2019; Muñoz et al., 2021). A pesar de este avance, monitores sociales sobre la Ley revelan obstáculos significativos en su implementación, como la objeción de conciencia, el déficit de información sobre la Ley, el aborto y procedimientos de aborto en profesionales de la salud y comunidad, así como los prejuicios y los mitos sobre el aborto (Alveal-Álamos et al., 2022; Casas et al., 2022; Mesa Acción por el Aborto en Chile [MAACH], 2023; Montero et al., 2022).

Los mitos en torno al aborto vinculados a riesgos para la salud son habituales. A nivel físico, el aborto ha sido identificado como una intervención peligrosa. En realidad, las complicaciones graves del aborto son raras cuando se practica en condiciones de legalidad (Faundes, 2015). De hecho, la muerte es más probable durante un parto que durante un aborto (Stevenson, 2021). A largo plazo el aborto ha sido relacionado con el cáncer de mama y la infertilidad (Patev & Hood, 2021). Aunque estudios meta analíticos avalan el vínculo entre el cáncer de mama y el aborto (Islam et al., 2022), otros los desmienten y alegan errores metodológicos (Tong et al., 2020). El Instituto Nacional del Cáncer en EE. UU., niega esta relación (Pagoto et al., 2023). La relación entre el aborto y la infertilidad también ha sido desmentida (Johnson et al., 2021). Por su parte, Ralph et al. (2019) sugieren que la salud de mujeres que abortaron no es peor que la de aquellas que llevaron embarazos a término tras no poder acceder a la práctica del aborto, e incluso, algunas diferencias indican una peor salud en el grupo que dio a luz.

Los mitos sobre el aborto se extienden al ámbito emocional (Patev & Hood, 2021), asociando el aborto con categorías diagnósticas como la "Depresión y Psicosis Postaborto" o el "Trauma Postaborto", desacreditadas por la Asociación Médica Estadounidense y no reconocidas en el DSM-5 ni en la CIE-11. La polémica persiste con respaldo de parte de la comunidad científica (Jacob et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2018) y refutación por parte de otros que señalan errores metodológicos y factores de riesgo preexistentes. Por ejemplo, circunstancias de embarazo no deseado, barreras políticas para el acceso, estigma del aborto, y variables personales como baja resiliencia, bajo apoyo social, insatisfacción con la relación de pareja, violencia de pareja, problemas de salud mental preexistentes y actitudes provida (Reardon, 2018; Rajkumar, 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). También hay literatura que indica efectos inocuos o mejoras en la salud mental postaborto. Por ejemplo, Holmlund et al. (2021) concluyen que los antecedentes de aborto no afectan a la autoeficacia temprana y bienestar psicológico de padres.

A pesar de lo comentado, la desinformación sobre los efectos del aborto a nivel físico y emocional es común (Berglas et al., 2017; Patev & Hood, 2021; Swartz et al., 2020). No solo entre los individuos, sino también en la información que prestan instituciones gubernamentales a la comunidad (Berglas et al., 2017). En lo referente al discurso político en Chile, Osorio-Rauld (2013) recoge como los parlamentarios hacen uso de la ciencia en sus argumentos, y a veces de la pseudo-ciencia, cuando sus discursos tienen un trasfondo ideológico y moral. Incluso Pagoto et al. (2023) afirman que nos encontramos al borde de una infodemia sobre el aborto alimentada por un panorama legislativo confuso y cambiante. En este marco, los mitos del aborto son utilizados como una herramienta política y propagandística por grupos polarizados en contra de esta práctica, estrategia de persuasión para evitar la proliferación de la práctica y leyes de despenalización (Swartz et al., 2020). Estos grupos suelen identificarse con creencias valóricas conservadoras en lo religioso y lo político, variables con mayor peso a la hora de explicar las actitudes negativas hacia el aborto (Alveal-Álamos et al., 2022; Camacho, 2019; Pérez, Burgos, et al., 2022; Pérez, Concha-Salgado, et al., 2022); y con actitudes de género tradicionales y una orientación hacia la dominancia social (Cárdenas, Lay, et al., 2010; Cárdenas, Meza, et al., 2010; Cárdenas et al., 2022; Pérez, Concha-Salgado, et al., 2022).

La escasez de evidencia que respalda la extensión de la desinformación sobre el aborto se aborda en la revisión sistemática de Patev y Hood (2021) que examinó nueve estudios en Estados Unidos. La investigación confirma la prevalencia de creencias en mitos sobre aborto y destaca que una parte significativa de la población mantiene dudas sobre su veracidad. Pocos trabajos indagan sobre las características asociadas con la desinformación. Littman et al. (2014), en una muestra de mujeres que practicaron un aborto, descubren que las mujeres mayores y con hijos respaldan menos el mito de la infertilidad, mientras que mujeres negras y con menor educación respaldan menos el mito de la depresión. Berglas et al. (2017), en una muestra de mujeres que solicitaron información sobre aborto, encuentran que mujeres jóvenes, no blancas y sin experiencias pasadas de aborto respaldan más los mitos sobre el aborto. Kavanaugh et al. (2013), en una muestra comunitaria, revelan que aquellos con menor conocimiento sobre el aborto tienen niveles educativos más bajos, menos conocimiento en salud sexual y reproductiva, y menor apoyo a la legalidad del aborto, sin diferencias de conocimiento entre hombres y mujeres. Swartz et al. (2020) señalan mayor desinformación en mujeres que desaprueban el aborto legal.

En Chile y otras regiones de Latinoamérica, no encontramos información que nos ayude a comprender la extensión y alcance de los mitos sobre el aborto y la desinformación. A tenor de la actual discusión legislativa sobre el aborto en Chile y el uso de la desinformación como estrategia política (Osorio-Rauld, 2013; Palma & Moreno, 2015; Swartz et al., 2020); además de sus consecuencias perjudiciales como la desconfianza en las recomendaciones de salud pública, afectación en la toma de decisión y capacidad de afrontamiento de mujeres que necesitan acceder al aborto, o en el trato estigmatizante recibido por parte de la comunidad y/o profesionales de la salud desinformados (Alveal-Álamos et al., 2022; Casas et al., 2022; Littman et al., 2014; MAACH, 2023; Montero et al., 2022; Pagoto et al., 2023), consideramos de relevancia contar con una medida corta y de fácil aplicación sobre creencias en mitos acerca de salud y aborto adaptada a la actual realidad sociocultural del país y con adecuadas propiedades psicométricas. Algunos de los trabajos revisados han desarrollado sus propias medidas para evaluar el conocimiento sobre mitos de aborto. Berglas et al. (2017) pidieron a las participantes que eligieran cuál de dos afirmaciones se acercaba más a la verdad sobre cinco mitos acerca de la seguridad del aborto y riesgos físicos y psicológicos a largo plazo. Ofrecieron la posibilidad de una tercera opción de respuesta: no sé/no estoy segura. Swartz et al. (2020) realizaron cinco preguntas utilizando mismo método. Littman et al. (2014) consultaron sobre mitos comunes mediante cuatro preguntas tipo Likert. Kavanaugh et al. (2013) incluyeron distintos tipos de preguntas de conocimiento sobre aborto en cuestionario de conocimiento sobre salud sexual y reproductiva: de selección múltiple entre cuatro opciones sobre prevalencia y probabilidad, siendo correcta solo una opción; de evaluación de riesgo relativo frente a diferentes situaciones de salud reproductiva; y expresión de nivel de acuerdo mediante escala Likert para evaluar el conocimiento sobre las consecuencias de diferentes situaciones. Sin embargo, ninguna de estas medidas presenta estudios sobre sus propiedades psicométricas. Además, han sido desarrollados de acuerdo a la realidad sociocultural de EEUU. Por ello, creemos pertinente el diseño de una medida con población chilena y de acuerdo a los mitos sobre salud y aborto extendidos en el país. En un trabajo anterior, Pérez, Burgos, et al. (2022) recabaron información para la formulación de ítems acerca de mitos sobre salud y aborto como parte del proceso de creación de la Escala de Actitudes hacia el Aborto Voluntario (EAAV). Para ello, además de revisar la literatura, contaron con análisis de entrevistas utilizadas en estudio previo con comunidad chilena (Pérez et al., 2020); análisis de representaciones sociales sobre la Interrupción Voluntaria del Embarazo (IVE) mediante grupo de discusión con activistas a favor del aborto libre; y una consulta de expertos con profesionales/investigadores del área. Los ítems acerca de mitos sobre salud y aborto cumplieron con indicadores de capacidad discriminativa en estudio piloto y muestra definitiva con 118 y 1.223 participantes respectivamente. No obstante, finalmente se descartados por presentar correlaciones bajas con otros ítems o por criterios teóricos. Estos ítems son recuperados en el presente estudio para el diseño de la EMSA.

2. Objetivos e hipótesis

En definitiva, se plantea como objetivo de este estudio diseñar y analizar las propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Mitos sobre Salud y Aborto (EMSA). De este objetivo se derivan otros:

(1) analizar los ítems descriptivamente;

(2) demostrar evidencia de validez en base a la estructura interna;

(3) comprobar el coeficiente de consistencia interna de las puntuaciones como evidencia de fiabilidad;

(4) demostrar evidencias de validez basada en la relación con otras variables: sociodemográficas (nivel educativo, edad y género), e ideológicas (religiosidad, orientación política, doble moral sexual y dominación social).

Kavanaugh et al. (2013) encontraron mayor respaldo de los mitos entre las personas de nivel educativo bajo en una muestra comunitaria. De acuerdo con ellos, se hipotetiza que las y los participantes con un nivel educativo más alto obtendrán menores puntuaciones en EMSA que las y los participantes con un nivel educativo más bajo (H1). En cuanto a la edad, en coherencia con los trabajos de Berglas et al. (2017) y Littman et al. (2014) se espera obtener mayor respaldo de los mitos entre las y los participantes jóvenes que entre las personas mayores (H2). Además, (H3) no se esperan diferencias en las puntuaciones de acuerdo con el género (Kavanaugh et al., 2013). Por otro lado, debido a la importancia de la identidad religiosa y política de derecha en la construcción de una opinión contraria a la IVE (Alveal-Álamos et al., 2022; Camacho, 2019; Pérez, Burgos, et al., 2022; Pérez, Concha-Salgado, et al., 2022; Pérez et al., 2020), el sesgo de confirmación (Myers & Twenge, 2019), que puede llevar a validar mitos sobre salud y aborto para el respaldo de las preconcepciones negativas sobre la IVE; el uso de la desinformación como estrategia política por parte de grupos en contra de la IVE (Osorio-Rauld, 2013; Palma & Moreno, 2015; Swartz et al., 2020); y que tanto Kavanaugh et al. (2013) como Swartz et al. (2020) identifican un mayor respaldo de la desinformación entre quienes apoyan la ilegalización del aborto, se espera que las y los participantes con mayores puntuaciones en los factores de la Escala de Involucramiento Religioso Universal (H4) y autoidentificados con la orientación política de derecha (H5) puntúen más alto en la EMSA, que quienes obtienen bajas puntuaciones en ambas escalas. Finalmente, se espera que las puntuaciones obtenidas en la EMSA correlacionen de manera significativa y positiva con las puntuaciones obtenidas en la Escala de Doble Estándar Sexual (H6); y con el factor de Dominación Social de la Escala de Orientación a la Dominancia Social (H8); y de manera negativa con el factor de la Oposición a la Igualdad (H7). Esto, debido a que la literatura relaciona un perfil ideológico conservador en lo religioso y político con las actitudes tradicionales sobre el género y la dominación social (Cárdenas et al., 2022; Cárdenas, Lay, et al., 2010; Cárdenas, Meza, et al., 2010; Pérez, Concha-Salgado, et al., 2022).

3. Método

3.1. Participantes

La muestra se compone de 613 participantes. Se utilizó un muestreo por conveniencia y cuotas: (a) macrozona geográfica (15,8% de zona norte, 58,2% de la zona centro, y el 25,9% de la zona sur) de acuerdo a la distribución de la densidad poblacional en el país; (b) sexo (51,4% hombres y 48,6% mujeres); (c) edad (50,6% entre 18 y 30 años, y 49,4% desde los 31 años en adelante); (d) y grupo socioeconómico (GSE), en base al sistema de clasificación de la Asociación de Investigadores de Mercado (33,3% a GSE Alto; 32,8% a GSE Medio; y 33,9% a GSE bajo). La media de edad fue de 37,14 años (DE = 15,30). En la Tabla 1 se recogen los datos descriptivos de la muestra total y las submuestras 1 y 2.

Tabla 1

Datos descriptivos de la muestra completa y por submuestras

|

Variables |

Categorías |

Muestra Total (N = 613) |

Submuestra 1 (n = 306; 49,9%) |

Submuestra 2 (n = 307; 50,1%) |

|||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

||

|

Género |

Femenino |

298 |

48,6 |

164 |

53,6 |

151 |

49,2 |

|

Masculino |

315 |

51,4 |

142 |

46,4 |

156 |

50,8 |

|

|

Edad |

Entre 18 y 30 años |

310 |

50,6 |

160 |

52,3 |

150 |

48,9 |

|

31 años y más |

303 |

49,4 |

146 |

47,7 |

157 |

51,1 |

|

|

Zona del país donde reside |

Norte |

97 |

15,8 |

58 |

19 |

39 |

12,7 |

|

Centro |

357 |

58,2 |

175 |

57,2 |

182 |

59,3 |

|

|

Sur |

159 |

25,9 |

73 |

23,9 |

86 |

28 |

|

|

Grupo socioeconómico

|

AB (Alto) |

20 |

3,3 |

11 |

3,6 |

9 |

2,9 |

|

C1a (Medio acomodado) |

69 |

11,3 |

35 |

11,4 |

34 |

11,1 |

|

|

C1b (Medio emergente) |

115 |

18,8 |

59 |

19,3 |

56 |

18,2 |

|

|

C2 (Medio típico) |

92 |

15,0 |

52 |

17 |

40 |

13 |

|

|

C3 (Medio bajo) |

109 |

17,8 |

56 |

18,3 |

53 |

17,3 |

|

|

D (Vulnerable) |

130 |

21,2 |

54 |

17,6 |

76 |

24,8 |

|

|

E (Pobre) |

78 |

12,7 |

39 |

12,7 |

39 |

12,7 |

|

|

Nivel educacional (estudios) |

Media completa o inferior |

165 |

26,9 |

83 |

27,1 |

82 |

26,7 |

|

Técnico/Universitario Incompleto |

217 |

35,4 |

105 |

34,3 |

112 |

36,5 |

|

|

Universitario o de postgrado |

231 |

37,7 |

118 |

38,6 |

113 |

36,8 |

|

|

Estado civil |

Soltero/a |

329 |

53,7 |

167 |

54,6 |

162 |

52,8 |

|

Casado/a |

138 |

22,5 |

69 |

22,5 |

69 |

22,5 |

|

|

Conviviente |

103 |

16,8 |

53 |

17,3 |

50 |

16,3 |

|

|

Separado/a, Divorciado/a |

37 |

6,0 |

15 |

4,9 |

22 |

7,2 |

|

|

Viudo |

6 |

1 |

2 |

0,7 |

4 |

1,3 |

|

|

Pueblo originario |

No |

510 |

83,2 |

252 |

82,4 |

258 |

84 |

|

Mapuche |

78 |

12,7 |

40 |

13,1 |

38 |

12,4 |

|

|

Otro |

25 |

4,1 |

14 |

4,6 |

11 |

3,6 |

|

|

Orientación política |

De izquierda |

140 |

22,8 |

74 |

24,2 |

66 |

21,5 |

|

Ni de izquierda ni de derecha |

403 |

65,7 |

189 |

61,8 |

214 |

69,7 |

|

|

De derecha |

70 |

11,4 |

43 |

14,1 |

27 |

8,8 |

|

3.2. Diseño

Este estudio se basa en un diseño instrumental (Ato et al., 2013). Se consideran las recomendaciones de Lloret-Segura et al. (2014) para la selección de la metodología sobre evidencia de validez y confiabilidad y la selección de análisis estadísticos para demostrarlas.

3.3. Instrumentos

3.3.1. Cuestionario sociodemográfico ad hoc.

Recoge aspectos como el género, la edad, la identificación étnica, la procedencia rural o urbana, el nivel educativo o la orientación política.

3.3.2. Escala de Mitos sobre Salud y Aborto (EMSA)

La EMSA (Anexo 1) evalúa el nivel de acuerdo con mitos/creencias erróneas sobre salud -física y mental- y aborto. La escala de respuesta es tipo Likert de cinco puntos, donde 1 significa muy en desacuerdo y 5 muy de acuerdo. A mayor puntuación, mayores creencias erróneas sobre salud y aborto. Para más información sobre las fases de diseño, consultar el trabajo de Pérez, Burgos, et al. (2022).

3.3.3. Escala de Involucramiento Religioso Universal (I-E 12)

La I-E 12 adaptada con escolares chilenos por Flores Jara et al. (2019), mide involucramiento religiosos a través de tres dimensiones: Orientación Intrínseca (OI) formado por seis ítems, saliencia de la categoría social religiosa frente a otras para la configuración del autoconcepto; Orientación Extrínseca Social (OES) formado por tres ítems, ganancia social a nivel de estatus e interacción personal; y Orientación Extrínseca Personal (OEP) formado por tres ítems, ganancia personal a nivel de protección y consuelo. La escala de respuesta es tipo Likert con cinco opciones de respuesta, donde 1 significa muy en desacuerdo y 5 muy de acuerdo. A mayor puntuación, mayor presencia de la dimensión en el participante. Esta estructura ajustó en una muestra comunitaria chilena (Pérez, Burgos, et al., 2022; Pérez, Concha-Salgado, et al., 2022). En este estudio, las tres dimensiones presentan una adecuada estimación de la fiabilidad de las puntuaciones (OI, α = ,924; OES, α = ,893; OEP, α = ,864).

3.3.4. Escala de Doble Estándar Sexual (DSS)

La DSS adaptada a población chilena universitaria (Díaz-Gutiérrez et al., 2022), mide doble moral sexual, es decir, la evaluación diferenciada de mismas conductas sexuales dependiendo del género de quien las realiza. Esta escala tipo Likert con cinco opciones de respuesta, donde 1 significa muy en desacuerdo y 5 muy de acuerdo, se compone de 10 ítems y es unidimensional. A mayor puntuación, mayor es la presencia del constructo en el participante. En el presente estudio, la estimación de la fiabilidad de las puntuaciones fue buena, con un valor de α = ,890.

3.3.5. Escala de Orientación a la Dominancia Social (SDO)

La SDO adaptada a población chilena por Cárdenas, Meza, et al. (2010) evalúa la predisposición de los individuos hacia el mantenimiento de relaciones intergrupales jerárquicas y no igualitaria. Esta escala cuenta con dos dimensiones en su versión chilena, de ocho ítems cada una: Dominación Grupal (DO), deseo de mantener el dominio y las jerarquías; Oposición a la Igualdad (OpI), resistencia al trato igualitario de los individuos. La SDO es una escala tipo Likert de 7 puntos, donde 1 significa totalmente en desacuerdo y 7 totalmente de acuerdo. A mayor puntuación, mayor presencia de ambos constructos. En el presente estudio, la estimación de la fiabilidad de las puntuaciones en ambas dimensiones fue buena: DO, α = ,853; OpI, α = ,906.

3.4. Procedimiento y resguardos éticos

Tras la aprobación del Comité de Ética Científico de la Universidad de La Frontera, el cuestionario fue sometido a un estudio piloto online por conveniencia con una muestra de 67 miembros de la comunidad, obtenida mediante muestre por bola de nieve. El 70% (n = 47) fueron mujeres, y la media de edad fue de 36.16 años. Se pidió a las y los participantes que informaran de aspectos confusos o de difícil comprensión sobre instrucciones e ítems. No fue necesario introducir ninguna modificación en la batería de instrumentos. Posteriormente, se obtuvo la muestra de estudio a través de la Empresa Netquest, empresa proveedora de datos para investigaciones y de mercado de acuerdo con la Norma ISO 26362:2009. Esta empresa cuenta con paneles especializados de participantes y registro de sus variables sociodemográficas. Esto permite la previa selección de participantes en base a cuotas por sexo, edad, zona geográfica y GSE. La aplicación online tuvo una duración aproximada de 15 minutos.

3.5. Estrategia de Análisis

Para la descripción de la muestra e ítems se utilizaron estadísticos descriptivos y de frecuencia. Para el análisis de la capacidad discriminativa de los ítems se consideraron los valores de asimetría y curtosis de cada ítem y la correlación ítem-total, asumiendo que los niveles más altos de +/- 1 en asimetría y curtosis, y más bajos de ,3 en correlación ítem-total, son indicadores de baja capacidad discriminativa. La normalidad multivariada se revisó mediante el coeficiente de Mardia. Además, se analizó la matriz de correlaciones entre los ítems con la pretensión de corroborar la relación significativa entre todos los ítems, y la ausencia de correlaciones demasiado altas (superiores a ,8) o demasiado bajas (inferiores a ,2), lo que podría ser indicativos de ítems redundantes o de ítems que no miden el mismo constructo que el resto.

Para el estudio de la estructura factorial de la EMSA se utilizó un procedimiento de validez cruzada dividiendo aleatoriamente la muestra en 2 submuestras. Con la submuestra 1, tras la comprobación de la idoneidad del tamaño muestral para realizar un Análisis Factorial Exploratorio (AFE), es decir, un tamaño mínimo de 200 participantes cuando las comunalidades se encuentra entre ,40 y ,70, con un mínimo de 3 o 4 ítems por factor; y de la calidad de la matriz de correlaciones mediante el índice de Bartlett y la prueba de Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO), se procedió a realizar un AFE considerando como proceso de extracción “Mínimos cuadrados no ponderados” y rotación oblimin directo. Además, se revisó el valor de Congruencia Unidimensional (UniCo), el Valor de Varianza común Explicada (ECV) y la Media de Cargas Absolutas Residuales del Item (MIREAL) para determinar si la escala puede considerarse esencialmente unidimensional (UniCo > ,95; ECV > ,85; MIREAL < ,30; Ferrando & Lorenzo-Seva, 2018).

Posteriormente, se replicó la estructura resultante en la submuestra 2 mediante Análisis Factorial Confirmatorio (AFC). Debido a que los datos eran ordinales, se consideró el estimador robusto de mínimos cuadrados no ponderados (ULSMV) en una matriz policórica. Se evaluó el ajuste de la estructura mediante los índices de ajuste absoluto, Raíz del Error Cuadrático Medio de Aproximación (RMSEA) e Índice de Bondad de Ajuste Global (GFI); y con los índices de ajuste incremental, Índice de Ajuste Comparativo (CFI), e Índice de Tucker-Lewis (TLI). Se consideró CFI, TLI y GFI ≥ ,95 y RMSEA < ,05 para un buen ajuste; y un CFI, TLI y GFI ≥ ,90 y un RMSEA < ,08 para un ajuste aceptable (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1999). Además, se analizó la validez convergente de los ítems mediante la varianza promedio extraída (AVE). El AVE es aceptable a partir de ,50, ya que el constructo debe compartir más de la mitad de la varianza con sus ítems (Fornell & Larcker ,1981). Una vez confirmada la estructura factorial, se analizó la consistencia interna de la estructura unidimensional resultante mediante el Alfa de Cronbach Estandarizado, además de con el Omega de McDonald, indicado en el caso de matrices policóricas (Elosua & Zumbo, 2008). Se consideró una buena consistencia interna desde ,70 para los tres coeficientes (George & Mayer, 2018).

El análisis de las evidencias de validez en relación con otros constructos y variables se llevó a cabo utilizando el coeficiente de correlación de Pearson (r); y la prueba T de Student para diferencia de medias con corrección de Welch cuando los tamaños de los grupos y/o las varianzas son desiguales. Los grupos de comparación se conformaron en base a la puntuación en variables sociodemográficas e ideológicas. En el caso del género, se compararon las puntuaciones en la EMSA entre hombres y mujeres. En el caso de la orientación política, se compararon a quienes se identificaron con la izquierda con quienes se identificaron con la derecha. Para el resto de las variables, se utilizó la estrategia de comparación de grupos extremos. Esto implica la selección de participantes con puntuaciones extremas, es decir, aquellas y aquellos participantes que conforman los cuartiles 1 y 4 en cada variable. Finalmente, se evaluó el tamaño del efecto mediante la d de Cohen (Cohen, 1988) y su nivel de confianza (Hedges & Olkin, 1985): efecto pequeño cuando d > 0,2, intermedio cuando d > 0,5, y grande cuando d > 0,8. Se utilizaron los paquetes estadísticos SPSS 24 para Windows, Mplus 7, Factor 10.9 y JASP 18.03.

4. Resultados

4.1. Análisis descriptivos de los ítems

En la Tabla 2, se recogen los análisis descriptivos de los ítems en la muestra completa (N = 613). Todos los valores presentan valores adecuados de asimetría y curtosis. A pesar de ello, no se cumple el supuesto de normalidad multivariada (Asimetría: Coeficiente de Mardia = 1.594, χ2 = 162,859, gl = 35, p < ,001; Curtosis: Coeficiente de Mardia = 42.608, z = 11,256, p < ,001). No obstante, los valores del índice de discriminación de los ítems (correlación ítem-total corregida), son superiores a ,3 en todos los casos; y ningún ítem alcanza una frecuencia del 95% en alguna opción de respuesta (las máximas frecuencias de respuesta oscilan entre 35,1% y 43,2%), síntoma de que los ítems son informativos y tienen capacidad para diferenciar entre participantes. Además, la matriz de correlaciones arroja valores estadísticamente significativos en todos los casos con valores que oscilan entre ,366 y ,662; y la eliminación de ítems podría afectar a la evidencia de validez de contenido. En consecuencia, ninguno de los ítems es eliminado.

4.2. Evidencias de validez basada en la estructura interna.

En submuestra 1 (n = 306), las comunalidades son superiores a ,4 salvo para el ítem 5. Esto es indicativo de la idoneidad del tamaño muestra. El índice KMO es igual a ,840 y el test de Esfericidad de Bartlett es estadísticamente significativo, χ2(10) = 589,4, p < ,001. Ambos datos son indicativos de que la matriz de correlaciones resulta apta para ser sometida a AFE. Como resultado se obtuvo una estructura unifactorial que explica el 65,7% de la varianza, con pesos factoriales que oscilan entre ,588 y ,716. Además, se obtuvo un valor de Unico = ,994; un valor de ECV = ,926; y un valor de MIREAL = ,199, lo que es indicativo de que los datos pueden ser tratados como esencialmente unidimensionales.

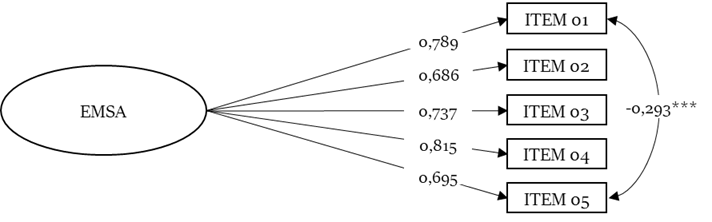

La estructura unidimensional se sometió a AFC en submuestra 2 (n = 307). Se obtuvo un adecuado ajuste, χ2 = 21,702; gl = 4; p < ,001; RMSEA = ,085 (IC 90% [,052 ,122]); CFI = ,993; TLI = ,982; GFI = ,995, tras correlacionar los errores de los ítems EMSA01 (Una mujer carga con el trauma del aborto toda su vida.) y EMSA05 (Las mujeres que abortan con medicamentos suelen tener riesgos en sus futuros embarazos). En la Figura 1 se recogen los pesos factoriales de los ítems de la escala. El AVE es de ,518.

Tabla 2

Descriptivos e índice de discriminación para la muestra completa y estadísticos del AFE y fiabilidad en ambas submuestras

|

|

|

Muestra completa |

|

SM 1 |

|

SM 2 |

|||||||

|

N |

Ítems |

|

M |

DE |

Asim. |

Curt. |

CI-T Corregida |

|

h2 |

λ AFE |

Ω si se elimina |

|

Ω si se elimina |

|

1 |

Una mujer carga con el trauma del aborto toda su vida. |

|

3,15 |

1,118 |

-,284 |

-,517 |

,634 |

|

,472 |

,764 |